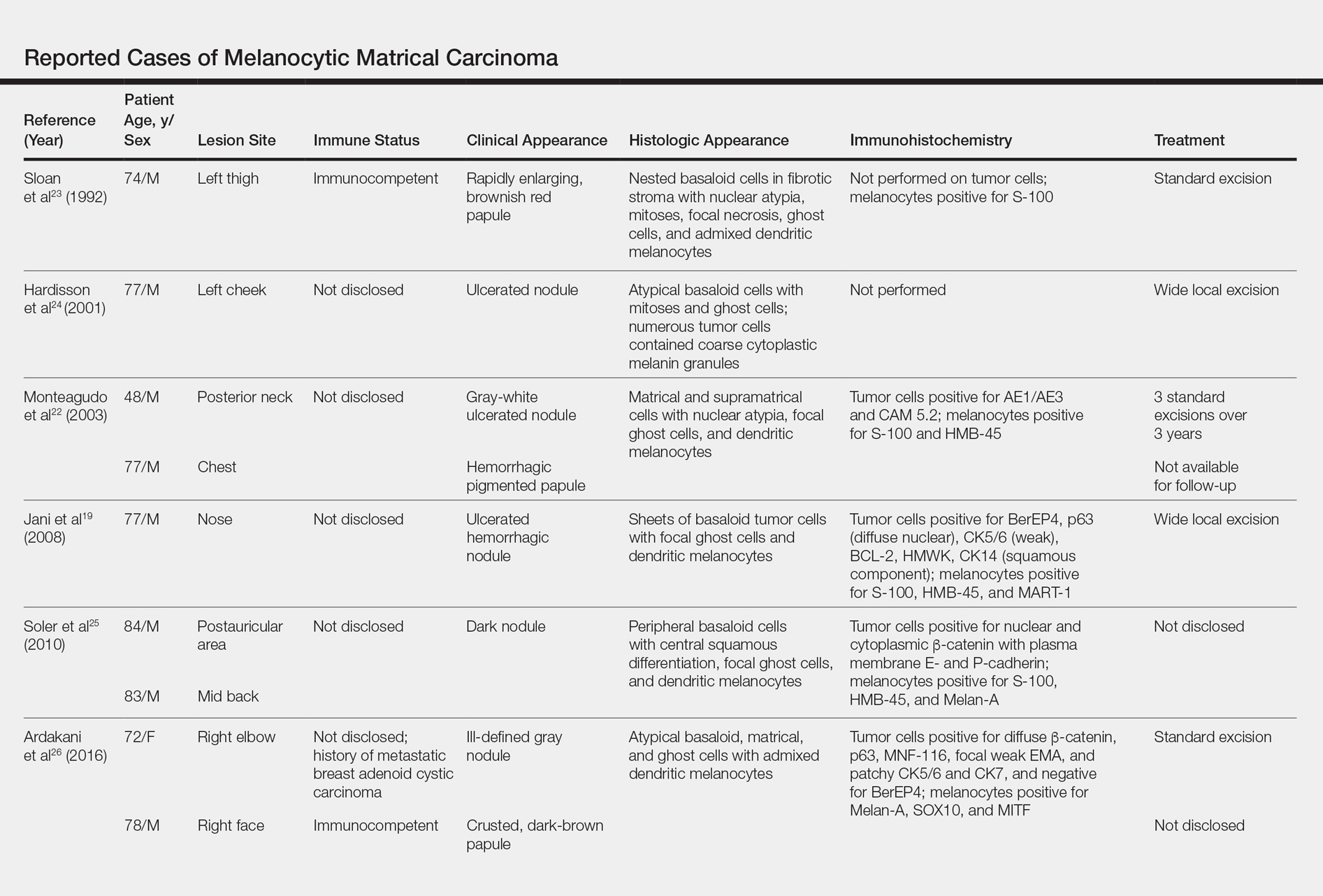

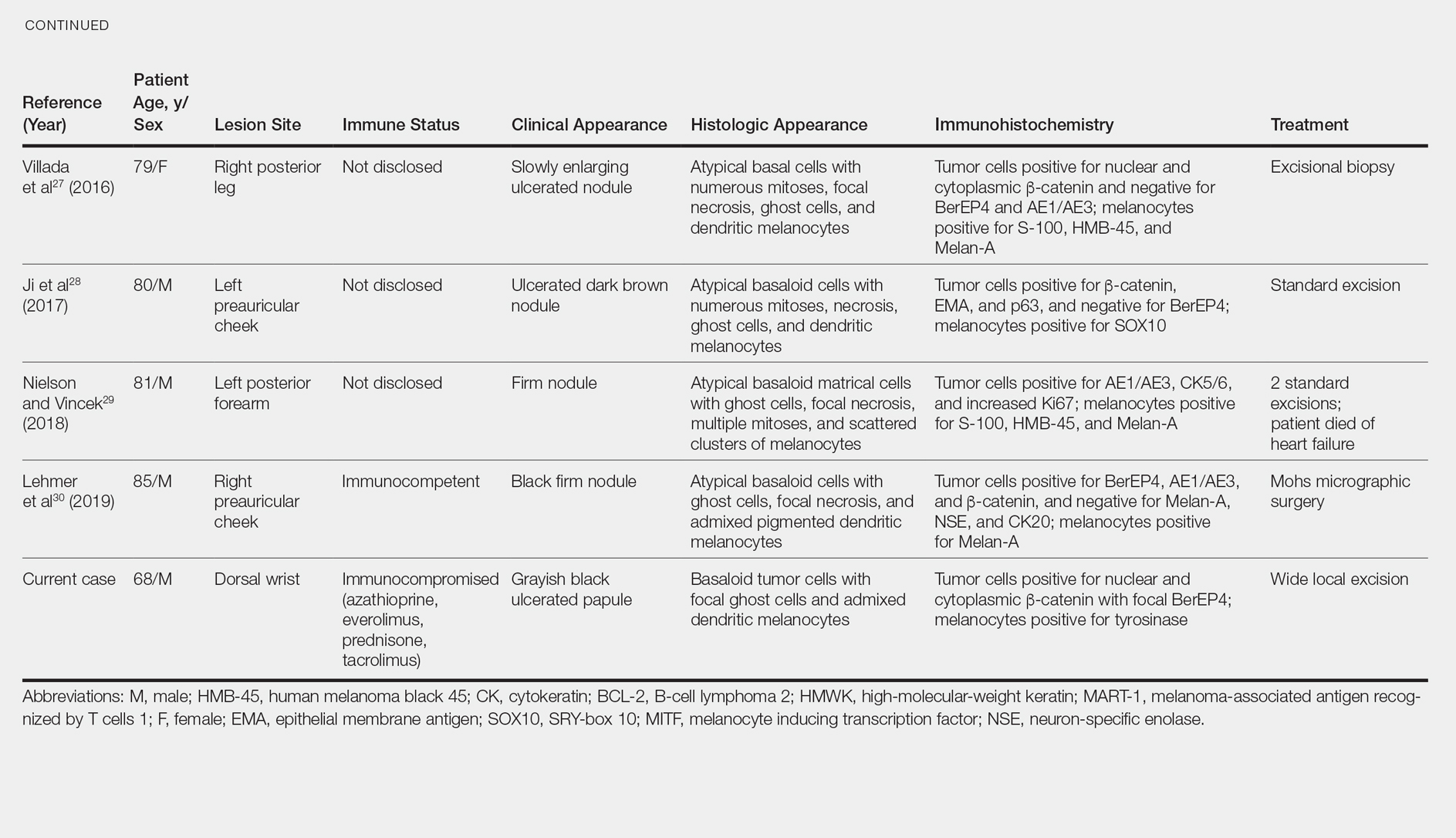

Melanocytic matrical carcinoma, also known as malignant MM or matrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia, may be considered the malignant counterpart to MM.22 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanocytic matrical carcinoma, malignant melanocytic matricoma, and matrical carcinoma with melanocytic hyperplasia, with review of references to identify additional citations, yielded 13 reported cases of MMC in the English-language literature (Table).19,22-30 As with MM, MMC is a biphasic tumor with basaloid matrical and supramatrical cells; focal areas of ghost cells; and admixed, banal-appearing dendritic melanocytes. However, the basaloid component also demonstrates nuclear atypia, mitoses, occasional ulceration, and variably poor circumscription. Clinically these lesions can mimic pigmented BCC, malignant melanoma, or other malignant adnexal tumors.25 Their natural history is unknown due to few reported cases, but they can be correlated with matrical carcinomas, which were first described by Weedon et al31 in 1980. A summary of more than 130 cases of matrical carcinomas in the English-language literature found that MMCs have high rates of local recurrence and metastasize in approximately 13% of cases. Wide local excision demonstrated lower rates of recurrence than simple excision (23% vs 83%), but there were insufficient cases to determine the incidence following Mohs micrographic surgery.32 Melanocytic matrical carcinomas also demonstrate mutations in the β-catenin pathway,pointing to a similar pathogenesis as their benign counterparts or perhaps direct malignant transformation.25,33,34

A subset of MMCs are combined cutaneous tumors (CCTs) consisting of epithelial neoplasms in close association with malignant melanocytes. Two of the more common variants include dermal squamomelanocytic tumors, a term first used by Pool et al,35 and malignant basomelanocytic tumors, as named by Erickson et al,36 but trichoblastomelanomas and other types have been documented.37 Although CCTs typically occur in the same patient populations as MMCs, namely elderly white men with chronically sun-damaged skin,they exhibit several important distinctions.37-39 By definition, CCTs have a malignant melanocytic component, whereas melanocytes are nonneoplastic in MMCs. The pathogenesis may differ as well. Various mechanisms for the close association of epithelial tumors and melanoma have been proposed, including field cancerization, tumor collision, tumor-tumor metastases, tumor colonization, and others, though CCTs likely arise through combinations of these processes depending upon their subtype.37-39 Paracrine signaling may play an important role in the pathogenesis of both tumors.5,6,8,38 As with MMCs, the prognosis of CCTs is limited by relatively few reported cases. Despite advanced Breslow depths in many cases, these tumors display more indolent behavior suggestive of melanoma in situ rather than invasive melanoma, perhaps due to dependence upon epithelial paracrine factors.37,39-42

Solid-organ transplant recipients have higher rates of more aggressive malignancies, of which skin cancer is the most common.43-49 Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin accounts for 95% of cutaneous malignancies in this population and occurs at approximately 65 times the rate of the general population.50 The risk of other skin cancers also is increased, though less dramatically, including BCC (10-fold increased risk) and melanoma (2- to 8-fold increased risk).46,50-53 The cause likely is multifactorial, including older age, history of skin cancer pretransplant, more than 5 years posttransplant, male sex, and incrementally as Fitzpatrick skin type decreases from VI to I.54-56 Immunosuppressive therapy also plays a role in tumorigenesis. Azathioprine metabolites have specifically been implicated in UVA radiation–induced promutagenic oxidative damage to DNA.57 Other studies have found no significant differences in the type of immunosuppressant used but instead have correlated rates of skin cancer to overall immunosuppression.48,55,58 Lung transplant recipients in particular demonstrate high rates of cutaneous malignancy, likely due in part to the necessity of more potent immunosuppressive regimens. Nearly one-third of patients develop a cutaneous malignancy by 5 years and nearly half by 10 years posttransplant.55

We report a rare case of MMC in a solid-organ transplant recipient. We hypothesize that the combination of UV radiation exposure–induced photodamage acquired pretransplant in addition to an aggressive immunosuppressive regimen with azathioprine and other agents posttransplant contributed to the development of this patient’s rare malignancy. Although rare, these tumors should remain in the differential diagnosis of clinicians and pathologists caring for this unique patient population.