Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

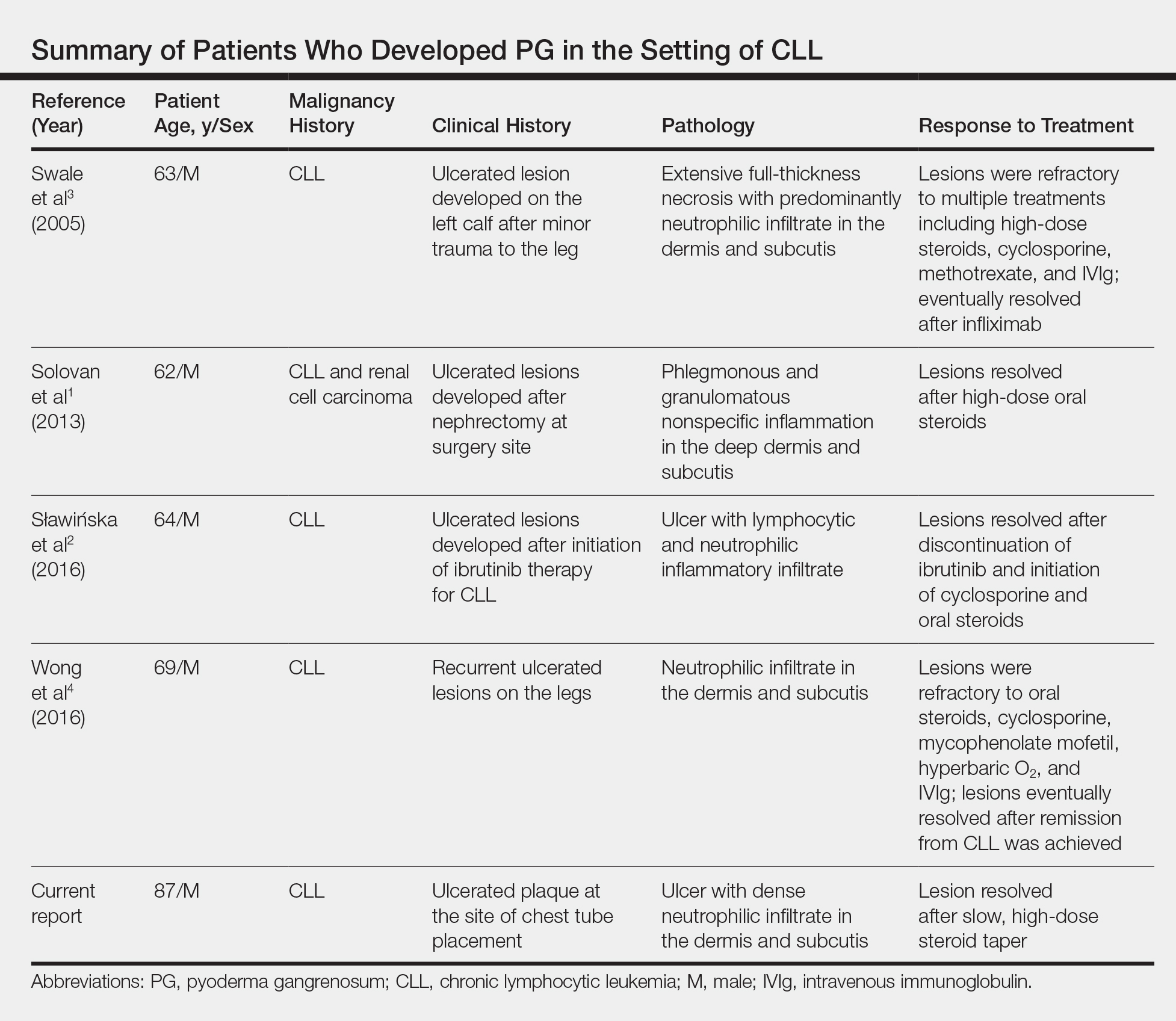

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.