Classification

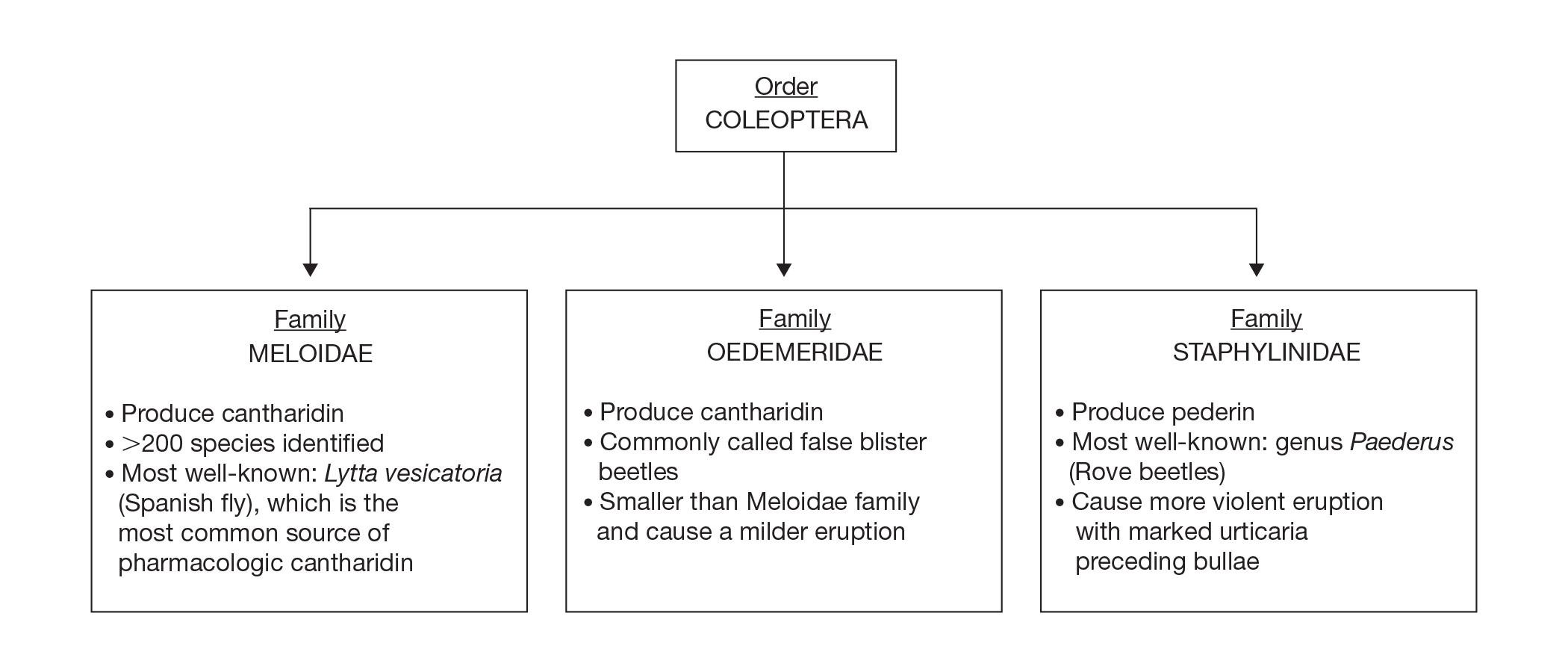

Blister beetles are both a scourge and the source of medical cantharidin (Figure 1). The term blister beetle refers to 3 families of the order Coleoptera: Meloidae, Oedemeridae, and Staphylinidae (Figure 2).

Meloidae is the most well-known family of blister beetles, with more than 200 species worldwide identified as a cause of blistering dermatitis.1 The most notorious is Lytta vesicatoria, also known as the Spanish fly. Although some blister beetles are inconspicuous in appearance, most are brightly colored and easily spotted, making them attractive to small children.2 They may be attracted to fluorescent lighting and commonly enter through open windows.3 Blister beetles do not bite or sting; rather, they release cantharidin via hemolymph, an oily yellow substance that is copiously expressed from the leg joints when disturbed by rubbing or pressing.1,3-5 Blistering also is associated with exposure to the contents of crushed beetles, which is the source of pharmacologic cantharidin.2,4,6

Oedemeridae are the smallest and least known beetles within the Coleoptera family. They often are called false blister beetles, which is a misnomer. Oedemeridae beetles also produce cantharidin, similar to Meloidae beetles; however, because Oedemeridae beetles are smaller, the vesiculobullous eruptions also are less pronounced.1

A third well-known family of blister beetles is the Staphylinidae family. Rove beetles (genus Paederus) differ from the Meloidae and Oedemeridae families in that they produce the vesicant pederin rather than cantharidin. Pederin causes a more violent eruption called dermatitis linearis, which often is associated with intense urticaria prior to blistering.1 Rove beetles are found in moist environments and tend to favor tropical and subtropical climates. They may emerge in large numbers after heavy rainfall.

Clinical Presentation

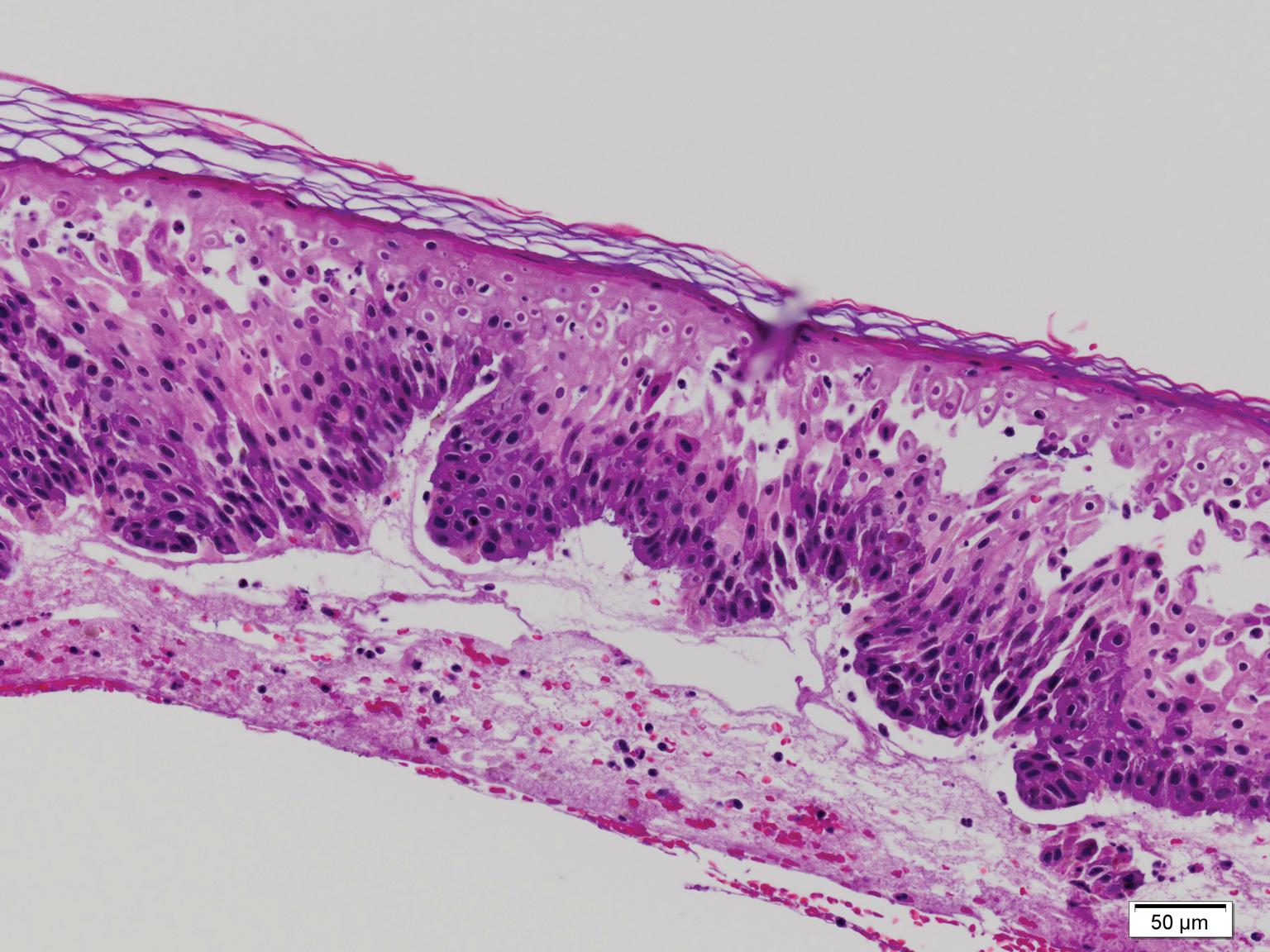

Blistering dermatitis—caused by exposure to cantharidin (families Meloidae and Oedemeridae) or pederin (genus Paederus)—begins as burning and tingling within minutes of exposure. Bullae later develop, often in a linear fashion, with subsequent bursting and crust formation.1,3 Secondary infection can occur.5 Exposure occurring on the elbows, knees, or mirroring skin folds results in lesions on opposing surfaces that come into contact, otherwise known as kissing lesions.1,3 Acantholysis of suprabasal keratinocytes can be seen on histologic sections of blisters (Figure 3)1,7 due to cantharidin activation of the serine/threonine protein phosphatases that cause detachment of tonofilaments from desmosomes.1,8 Washing of exposed sites with soap or alcohol can potentially prevent development of blistering dermatitis; however, lesions usually heal without complication when treated with topical antibiotics.3

Figure 3. Typical histopathologic features of a dermatologic reaction to cantharidin (H&E, original magnification ×200). An intraepidermal vesicle demonstrating both acantholysis (as in pemphigus vulgaris) and superficial necrosis (as in a toxic response to topical agents). These features are typical for a reaction to cantharone, the active ingredient in blister beetle fluid.