One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

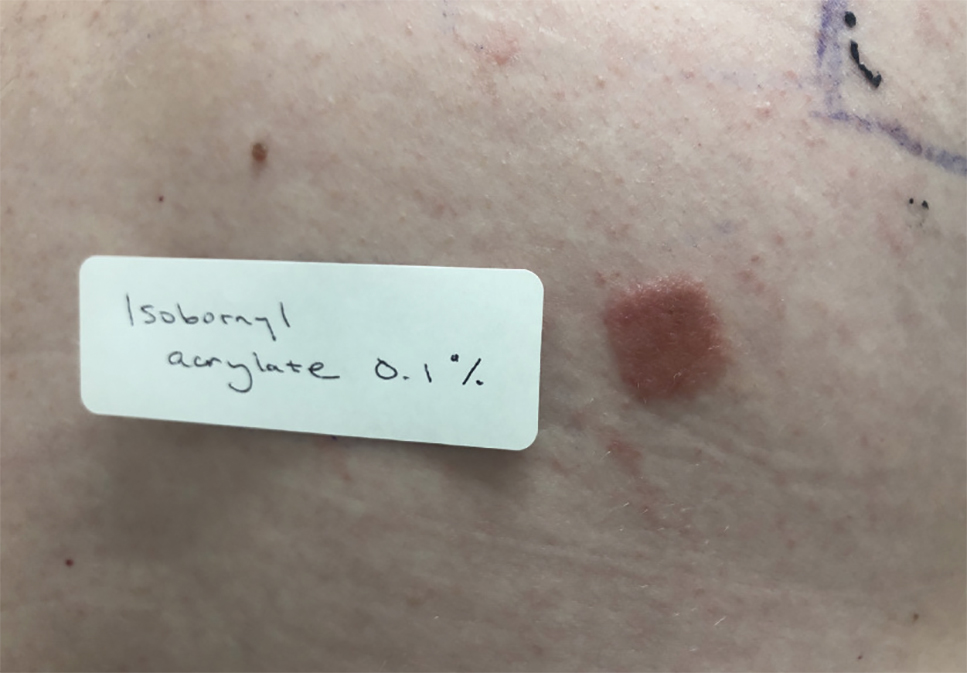

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.