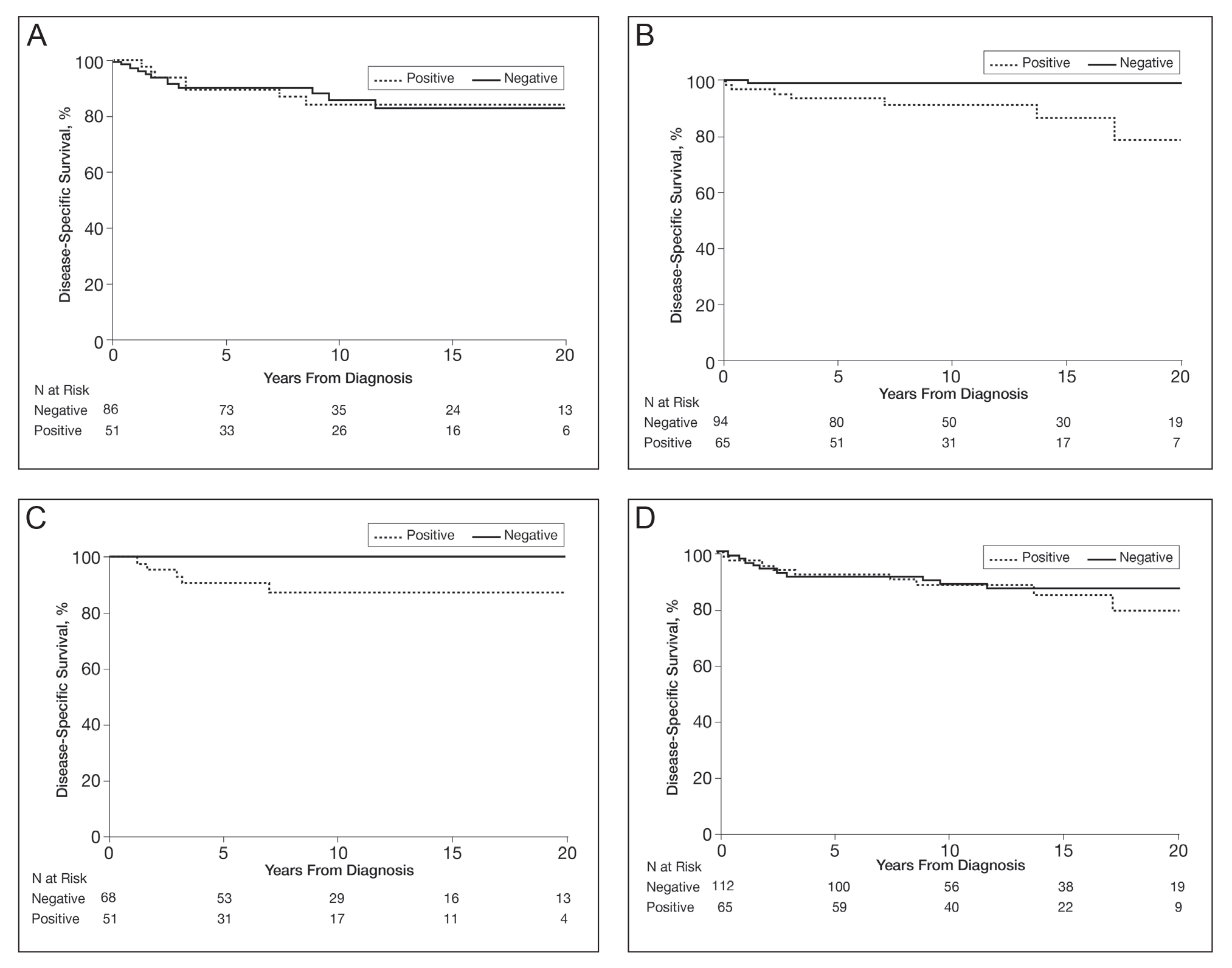

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).