San Diego – .

“I don’t think that’s going to change in the short term,” Travis W. Blalock, MD, director of dermatologic surgery, Mohs micrographic surgery, and cutaneous oncology at Emory University, Atlanta, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update. “But I do think we can supplement that with other modalities that will improve the clinical examination and help dermatopathologists as they assess and evaluate these lesions,” he said, adding: “The reality is, histopathology, while it may be the gold standard, is not necessarily a consistently reproducible evaluation. That raises the question: What can we do better?”

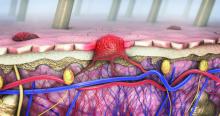

According to Dr. Blalock, the future may include more routine use of noninvasive genetic molecular assays to assist with the diagnostics challenges linked to the visual image and pattern recognition approach of detecting cutaneous melanoma. For example, a two-gene classification method based on LINC00518 and preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) gene expression was evaluated and validated in 555 pigmented lesions obtained noninvasively via adhesive patch biopsy.

“Today, you can pick up a kit from your local pharmacy that can tell you a bit about broad genetic susceptibilities,” he said at the meeting, which was hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. He predicted that using adhesive patch biopsies to assess suspicious melanocytic lesions “is likely the wave of the future.” This may increase patient understanding “as to the types of risks they have, the different lesions they have, and minimize invasive disease, but it also will pose different challenges for us when it comes to deploying patient-centered health care. For example, in a patient with multiple different lesions, how are you going to keep track of them all?”

Dermoscopy

In Dr. Blalock’s clinical opinion, dermoscopy improves the sensitivity of human visual detection of melanoma and may allow detection before a lesion displays classical features described with the “ABCDE rule.” However, the learning curve for dermoscopy is steep, he added, and whether the technique should be considered a first-line tool or as a supplement to other methods of examining cutaneous lesions remains a matter of debate.

“Dermoscopy is our version of the stethoscope,” he said. “We need to figure out when we’re going to use it. Should we be using it all of the time or only some of the time? Based on the clinical setting, maybe it’s a personal choice, but this can be a helpful skill and art in your practice if you’re willing to take the time to learn.”

In 2007, the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS) established a proposal for the standardization and recommended criteria necessary to effectively convey dermoscopic findings to consulting physicians and colleagues. The document includes 10 points categorized as either recommended or optional for a standardized dermoscopy report.

“The first step is to assess the lesion to determine whether or not it’s melanocytic in the first place,” said Dr. Blalock. “There are many different features – the mile-high [global features] evaluation of the lesions – then more specific local features that may clue you in to specific diagnoses,” he noted. “Once we get past that first step of determining that a lesion is melanocytic, it’s not enough to stop there, because we don’t want to biopsy every single lesion that’s melanocytic,” so there is a need to determine which ones require intervention, which is where dermoscopy “gets trickier and a little more challenging.”

According to the IDS, a standard dermoscopy report should include the patient’s age, relevant history pertaining to the lesion, pertinent personal and family history (recommended); clinical description of the lesion (recommended); the two-step method of dermoscopy differentiating melanocytic from nonmelanocytic tumors (recommended); and the use of standardized terms to describe structures as defined by the Dermoscopy Consensus Report published in 2003.

For new terms, the document states, “it would be helpful” for the physician to provide a working definition (recommended); the dermoscopic algorithm used should be mentioned (optional); information on the imaging equipment and magnification (recommended); clinical and dermoscopic images of the tumor (recommended); a diagnosis or differential diagnosis (recommended); decision concerning management (recommended), and specific comments for the pathologist when excision and histopathologic examination are recommended (optional).

The 2007 IDS document also includes a proposed seven-point checklist to differentiate between benign and melanocytic lesions on dermoscopy. Three major criteria are worth two points each: The presence of an atypical pigment network, gray-blue areas (commonly known as the veil), and an atypical vascular pattern. Four minor criteria are worth one point each: Irregular streaks, irregular dots/globules, irregular pigmentation, and regression structures. A minimum total score of 3 is required to establish a diagnosis of melanoma.

Another diagnostic technique, digital mole mapping, involves the use of photography to detect new or changing lesions. Dr. Blalock described this approach as rife with limitations, including variations in quality, challenges of storing and maintaining records, cost, time required to evaluate them, and determining which patients are appropriate candidates.

Other techniques being evaluated include computer algorithms to help dermatologists determine the diagnosis of melanoma from dermoscopic images, electrical impedance spectroscopy for noninvasive evaluation of atypical pigmented lesions, and ultrasound for staging of cutaneous malignant tumors.

Ultimately, “I think we’ll have multiple tools in our belt,” Dr. Blalock said, adding, “How do we pull them out at the right time to improve the lives of our patients? Are we going to use ultrasound? Dermoscopy? Integrate them with some of the genetic findings?”

Dr. Blalock disclosed that he has served as a principal investigator for Castle Biosciences.