Acne vulgaris, or acne, is a highly common inflammatory skin disorder affecting up to 85% of the population, and it constitutes the most commonly presenting chief concern in routine dermatology practice.1 Older teenagers and young adults are most often affected by acne.2 Although acne generally is more common in males, adult-onset acne occurs more frequently in women.2,3 Black and Hispanic women are at higher risk for acne compared to those of Asian, White, or Continental Indian descent.4 As such, acne is a common concern in all women of childbearing age.

Concerns for maternal and fetal safety are important therapeutic considerations, especially because hormonal and physiologic changes in pregnancy can lead to onset of inflammatory acne lesions, particularly during the second and third trimesters.5 Female patients younger than 25 years; with a higher body mass index, prior irregular menstruation, or polycystic ovary syndrome; or those experiencing their first pregnancy are thought to be more commonly affected.5-7 In fact, acne affects up to 43% of pregnant women, and lesions typically extend beyond the face to involve the trunk.6,8-10 Importantly, one-third of women with a history of acne experience symptom relapse after disease-free periods, while two-thirds of those with ongoing disease experience symptom deterioration during pregnancy.10 Although acne is not a life-threatening condition, it has a well-documented, detrimental impact on social, emotional, and psychological well-being, namely self-perception, social interactions, quality-of-life scores, depression, and anxiety.11

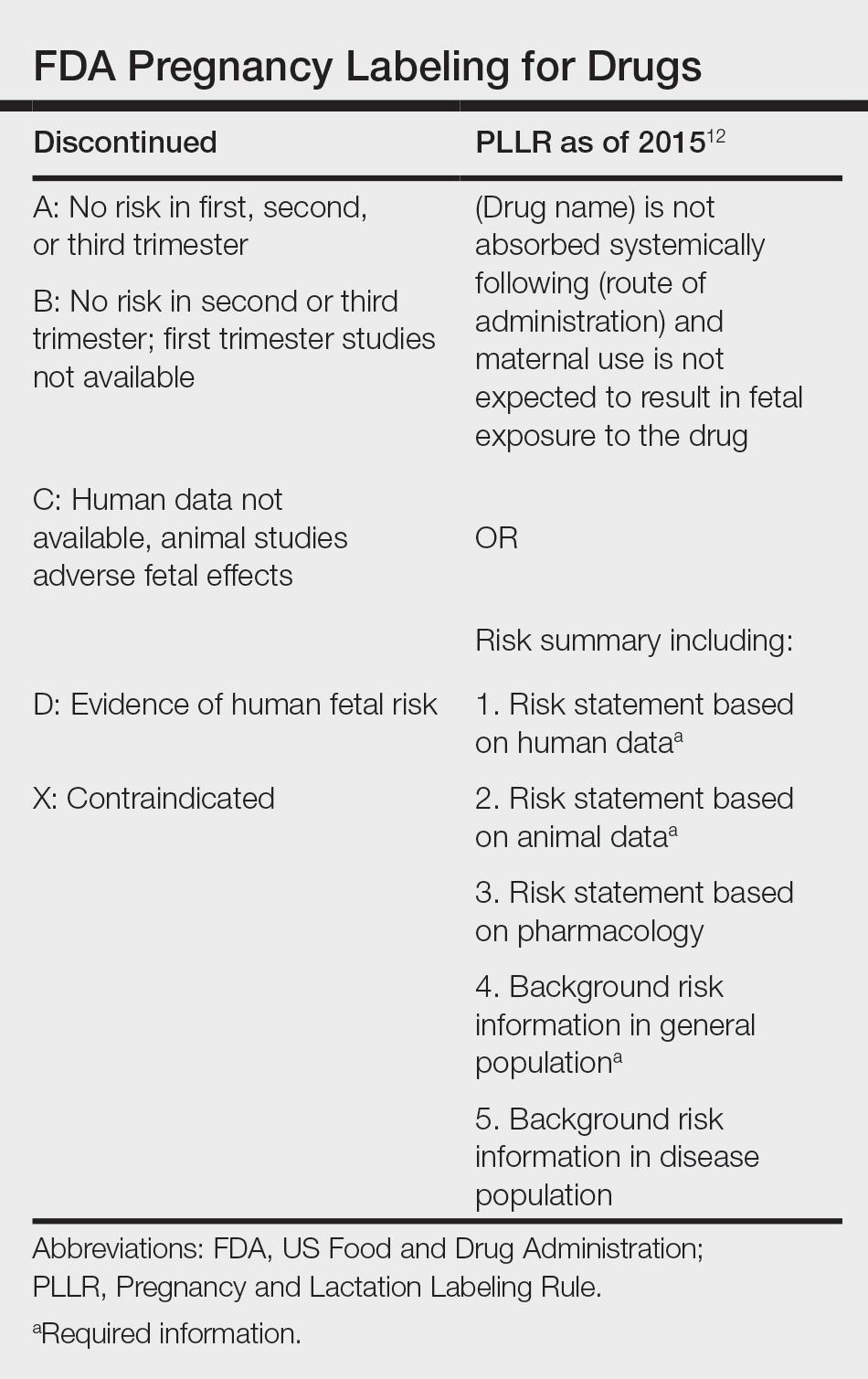

Therefore, safe and effective treatment of pregnant women is of paramount importance. Because pregnant women are not included in clinical trials, there is a paucity of medication safety data, further augmented by inefficient access to available information. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy safety categories were updated in 2015, letting go of the traditional A, B, C, D, and X categories.12 The Table reviews the current pregnancy classification system. In this narrative review, we summarize the most recent available data and recommendations on the safety and efficacy of acne treatment during pregnancy.

Topical Treatments for Acne

Benzoyl Peroxide—Benzoyl peroxide commonly is used as first-line therapy alone or in combination with other agents for the treatment of mild to moderate acne.13 It is safe for use during pregnancy.14 Although the medication is systemically absorbed, it undergoes complete metabolism to benzoic acid, a commonly used food additive.15,16 Benzoic acid has low bioavailability, as it gets rapidly metabolized by the kidneys; therefore, benzoyl peroxide is unlikely to reach clinically significant levels in the maternal circulation and consequently the fetal circulation. Additionally, it has a low risk for causing congenital malformations.17

Salicylic Acid—For mild to moderate acne, salicylic acid is a second-line agent that likely is safe for use by pregnant women at low concentrations and over limited body surface areas.14,18,19 There is minimal systemic absorption of the drug.20 Additionally, aspirin, which is broken down in the body into salicylic acid, is used in low doses for the treatment of pre-eclampsia during pregnancy.21

Dapsone—The use of dapsone gel 5% as a second-line agent has shown efficacy for mild to moderate acne.22 The oral formulation, commonly used for malaria and leprosy prophylaxis, has failed to show associated fetal toxicity or congenital anomalies.23,24 It also has been used as a first-line treatment for dermatitis herpetiformis in pregnancy.25 Although the medication likely is safe, it is better to minimize its use during the third trimester to reduce the theoretical risk for hyperbilirubinemia in the neonate.17,26-29

Azelaic Acid—Azelaic acid effectively targets noninflammatory and inflammatory acne and generally is well tolerated, harboring a good safety profile.30 Topical 20% azelaic acid has localized antibacterial and comedolytic effects and is safe for use during pregnancy.31,32