Results

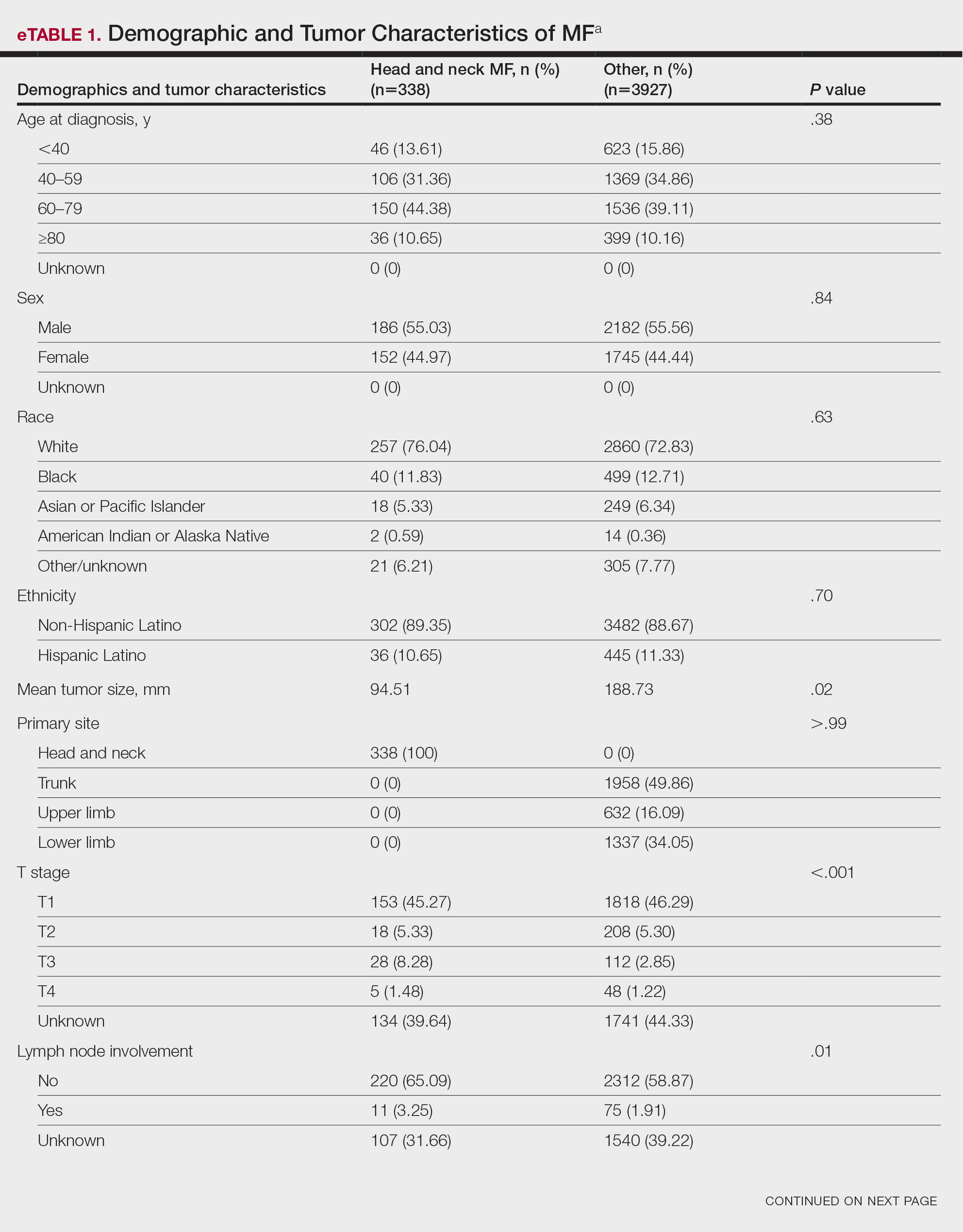

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics—There were 4265 patients diagnosed with MF from 2000 to 2019. The overall incidence of MF was 2.55 per million (95% CI, 2.48-2.63) when age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population, which increased with time (mean APC, 0.97% per year; P=.01). The mean age at diagnosis was 56.4 years with a male to female ratio of 1.2:1. Males (3.07 per million; 95% CI, 2.94-3.20) had a higher incidence of MF than females (2.16 per million; 95% CI, 2.06-2.26), with incidence in females increasing over time (mean APC, 1.52% per year; P=.02) while incidence in males remained stable (mean APC, 1.09%; P=.37). Patients predominantly self-identified as White (73.08%). Patients with MF of the head and neck were more likely to have smaller tumors (P=.02), a more advanced T stage (P<.001), and lymph node involvement (P=.01) at the time of diagnosis. Additional demographics and tumor characteristics are summarized in eTable 1.

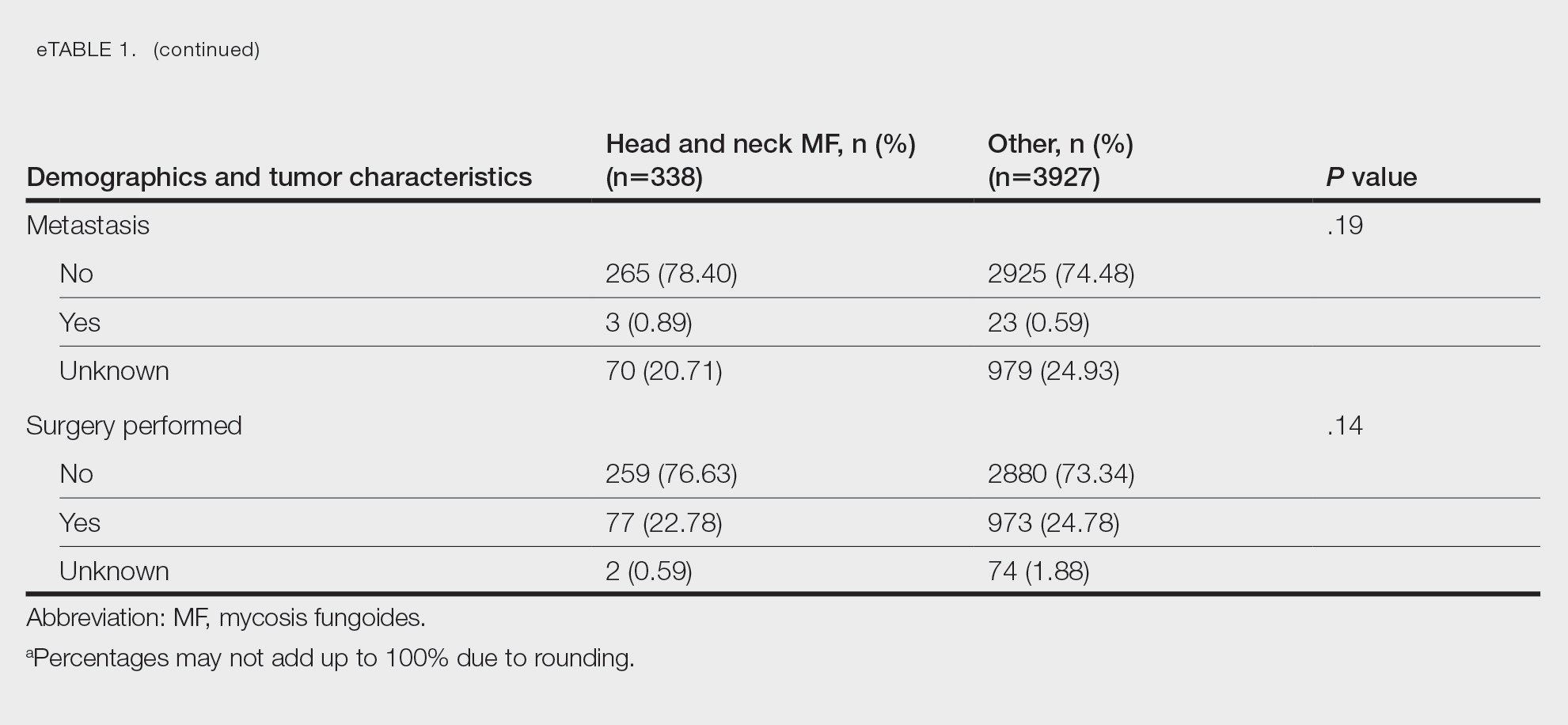

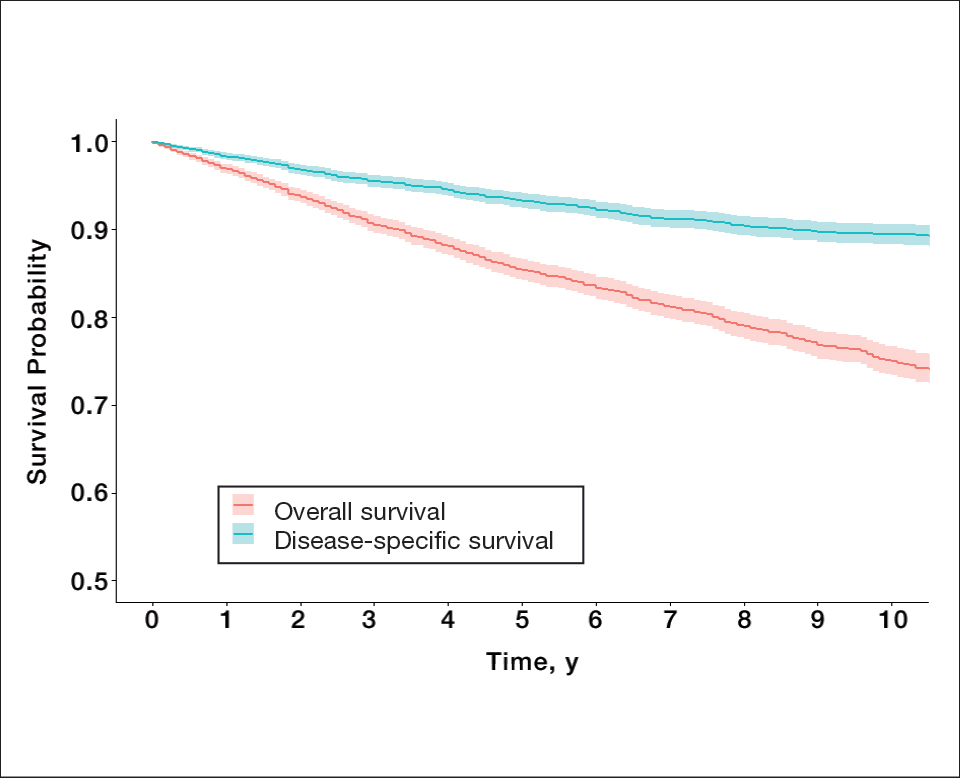

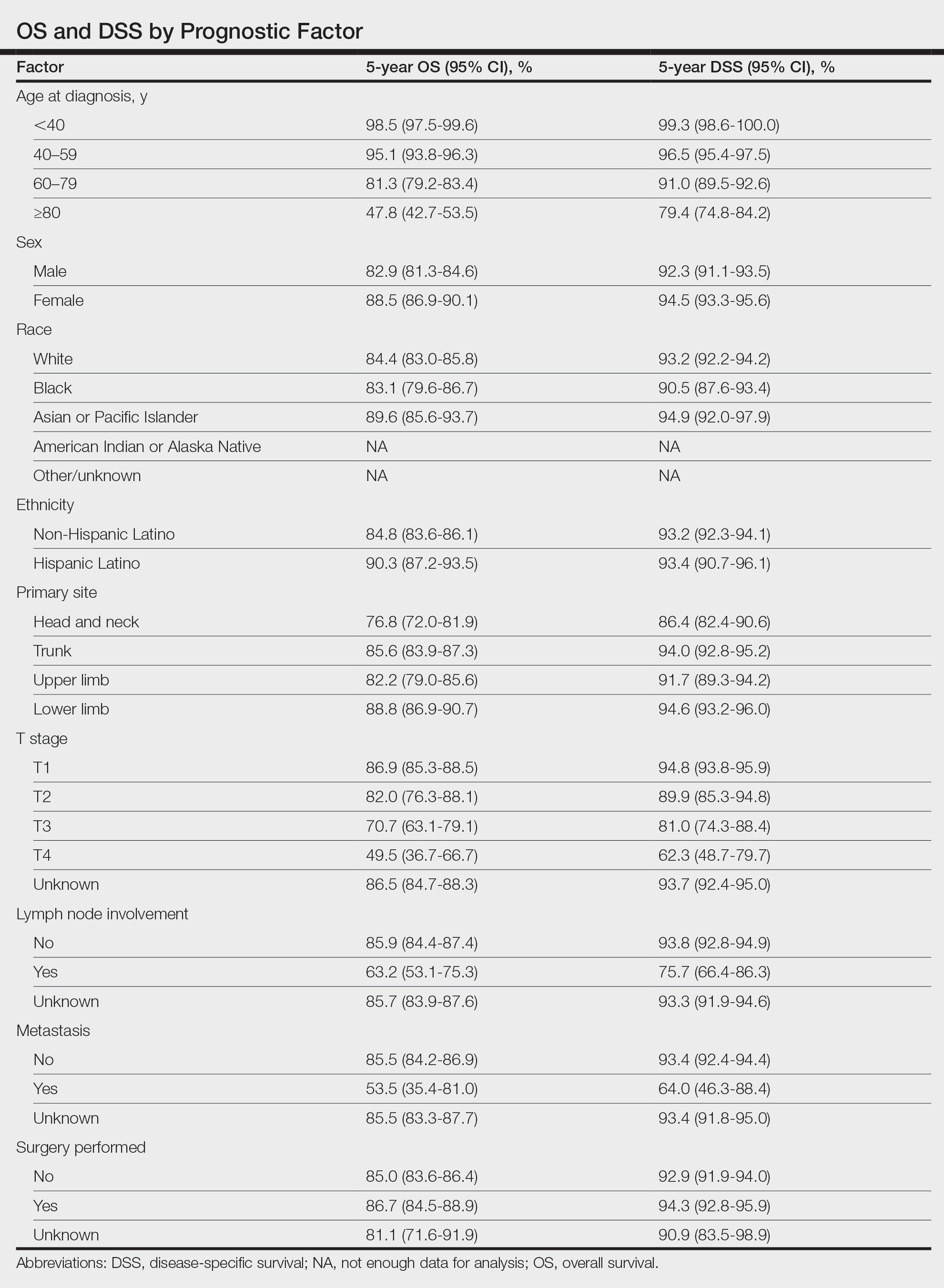

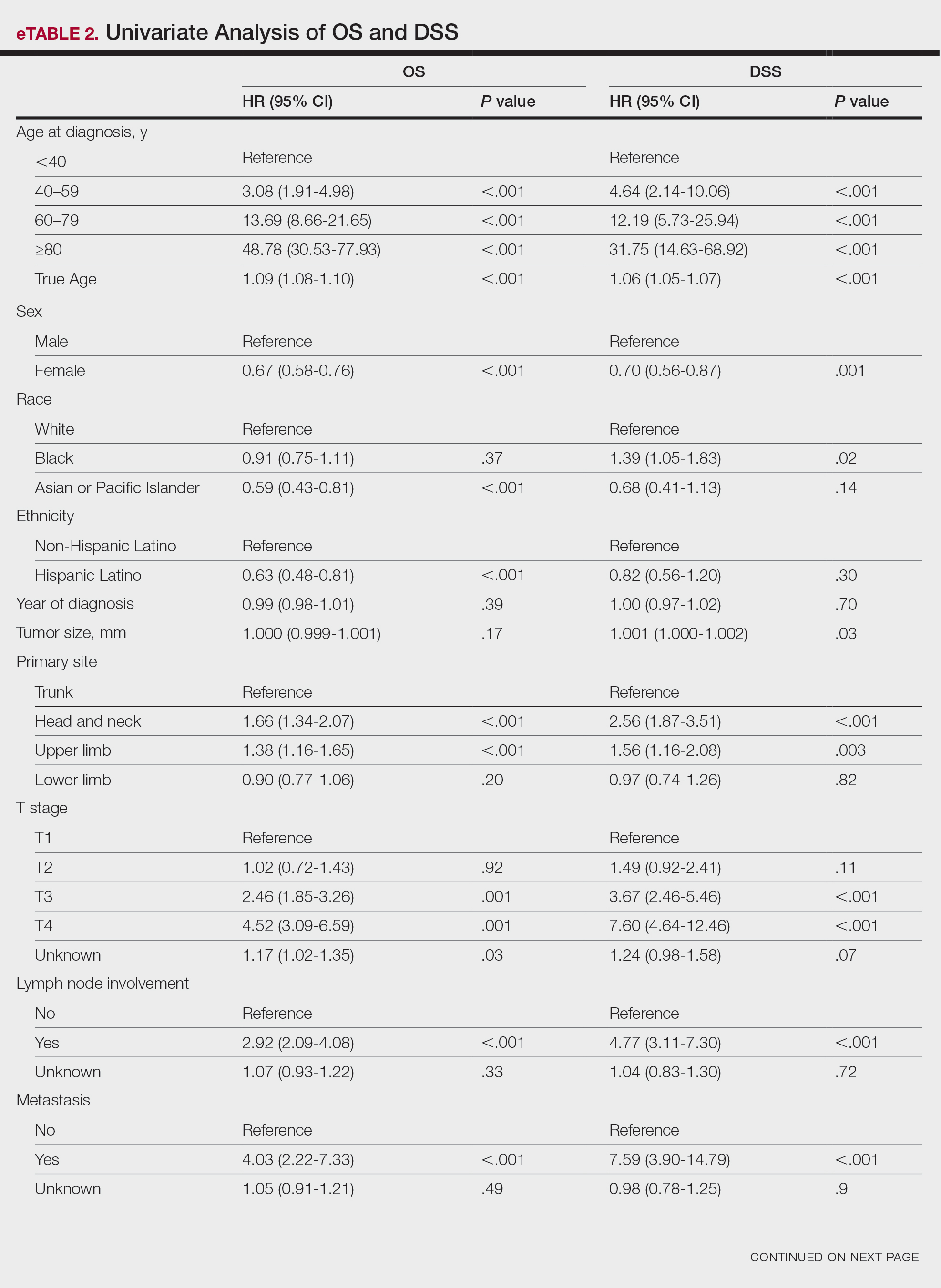

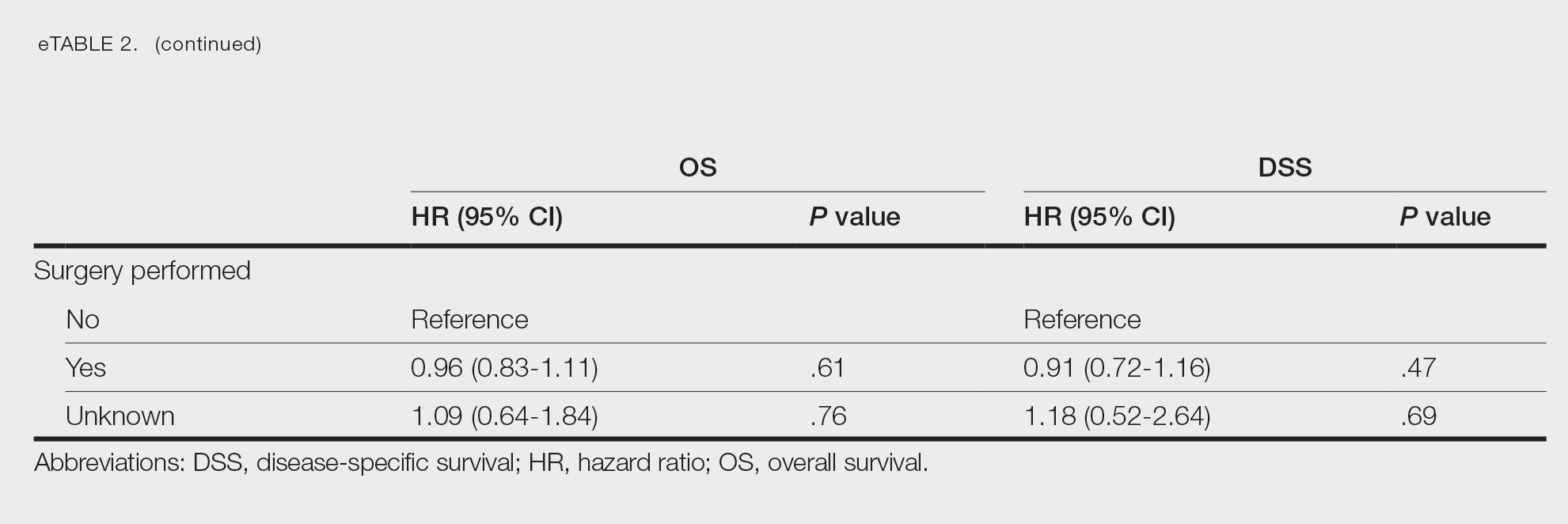

Survival Outcomes—The mean follow-up time was 86.9 months. The 5- and 10-year OS rates were 85.4% (95% CI, 84.2%-86.6%) and 75.0% (95% CI, 73.4%-76.7%), respectively (Figure 1)(Table). The 5- and 10-year DSS rates were 93.3% (95% CI, 92.4%-94.1%) and 89.5% (95% CI, 88.3%-90.6%), respectively. For OS, univariate analysis indicated that significant prognostic factors included increasing age (P<.001), female sex (P<.001), self-identifying as Asian or Pacific Islander (P<.001), self-identifying as Hispanic Latino (P<.001), primary tumor sites of either the head and neck or upper limb (P<.001), T3 or T4 staging (P=.001), lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis (P<.001), and metastasis (P<.001).

For DSS, univariate analysis had similar risk factors with self-identifying as Black being an additional risk factor (P=.02), though self-identifying as Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic Latino were not significant nor was location on the lower limb. For recorded tumor size, the HR increased by 1.001 per each 1-mm increase in size (eTable 2).

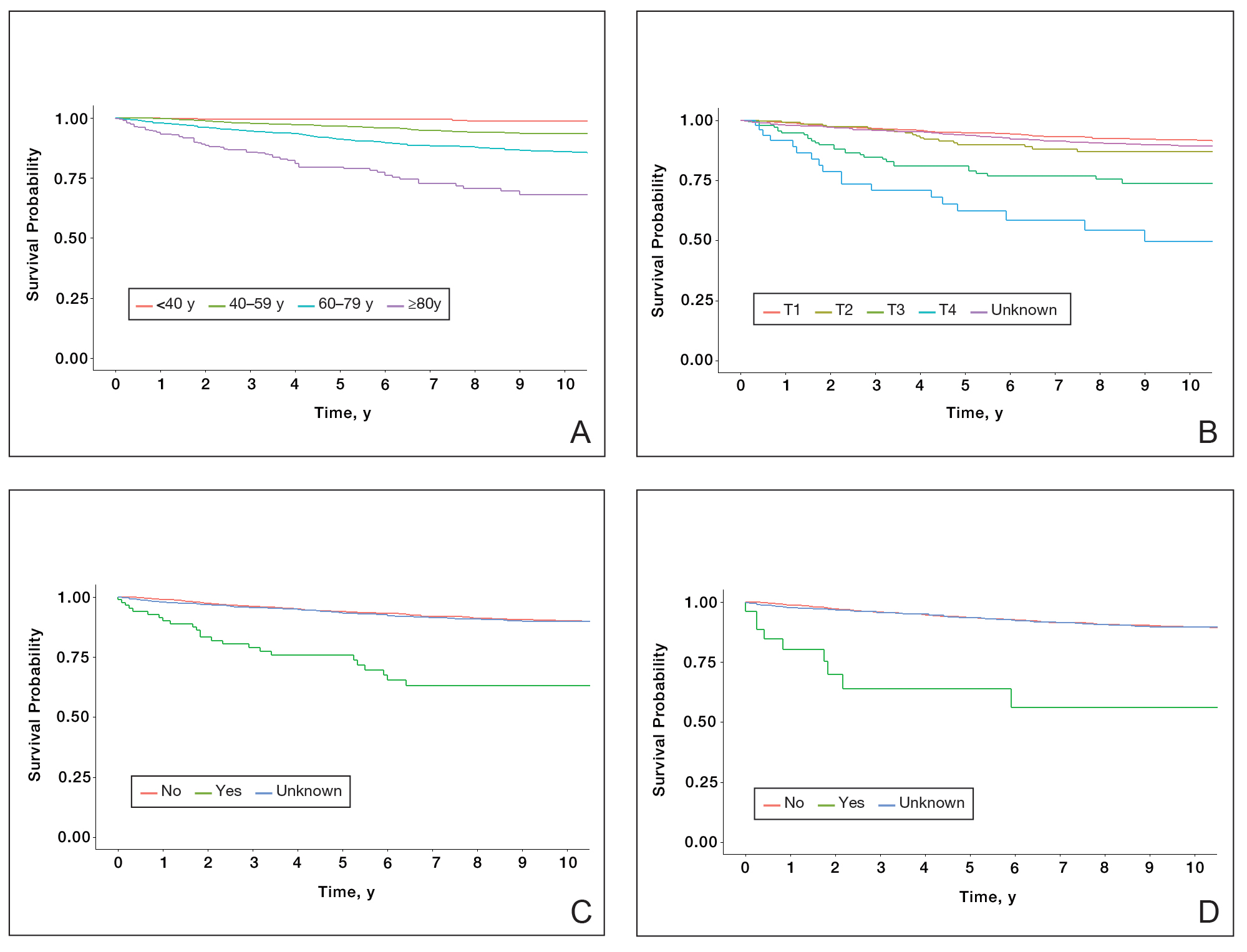

Multivariate analysis showed age at diagnosis (60–79 years: HR, 23.11 [95% CI, 3.03-176.32]; P=.002; ≥80 years: HR, 92.41 [95% CI, 11.78-724.75]; P<.001), T3 staging (HR, 2.37 [95% CI, 1.32-4.27]; P=.004), and metastasis (HR, 40.14 [95% CI, 4.14-389.50]; P=.001) significantly influenced OS. For DSS, multivariate analysis indicated the significant prognostic factors were age at diagnosis (60–79 years: HR, 8.94 [95% CI, 1.16-69.23]; P=.04];≥80 years: HR, 26.71; [95% CI, 3.26-218.99]; P=.002), tumor size (HR, 1.001 [95% CI, 1.000-1.002]; P=.04), T3 staging (HR, 3.71 [95% CI, 1.58-8.67]; P=.003), lymph node involvement (HR, 3.87 [95% CI, 1.11-13.50]; P=.03) and metastasis (HR, 49.76 [95% CI, 4.03-615.00]; P=.002)(Figure 2). When controlling for the aforementioned factors, the primary disease site was not significant (eTable 3).

Comment

Although the prognostic significance of primary disease sites on various types of CTCLs has been examined, limited research exists on MF due to its rarity. For the 4265 patients with MF included in our study, statistically significant prognostic factors on multivariate analysis for DSS included age at diagnosis, tumor size, T staging, lymph node involvement, and presence of metastasis. For OS, only age at diagnosis, T staging, and presence of metastasis were statistically significant predictors. Although initially statistically significant on univariate analysis for both OS and DSS, tumor location was not significant when controlling for confounders.

Our population-based analysis found that 5- and 10-year OS for patients with head and neck MF were 85.4% and 75.0%, respectively, and 5- and 10-year DSS were 93.3% and 89.5%, respectively. Our 10-year OS survival rate of 75.0% was slightly worse than the 81.6% reported by Jung et al16 in a study of 39 cases of MF of the head and neck from the Asan Medical Center database. The difference in survival rate may not only be due to differences in sample size but also because the Asan Medical Center database had a higher proportion of Asian patients as a Korean registry. In our univariate analysis, Asian/Pacific Islander race was shown to be a statistically significant predictor of worse prognosis for OS (P<.001). When comparing survival in patients with head and neck MF vs all primary tumor sites, our OS rate for head and neck MF was more favorable than the 5-year OS of 75% reported by Agar et al21 in their analysis of 1502 patients with MF of all locations, though their cohort also included patients with SS, which is known to have a poorer prognosis. Additionally, our 10-year OS rate of 75.0% for patients with MF with a primary tumor site of the head and neck was slightly less favorable than the 81.0% reported by a prior analysis of the SEER database for MF of all locations,22 which initially may be suggestive of worse outcomes associated with MF originating from the head and neck.

Although MF originating in the head and neck region was found to be a statistically significant prognostic factor under univariate analysis (P<.001), tumor location was not significant upon adjusting for confounders in the multivariate analysis. These results are consistent with those reported in a multivariable analysis conducted by Jung et al,16 which compared 39 cases of head and neck MF to 85 cases without head and neck involvement. The investigators found that the head and neck as the primary site was a significant prognostic factor associated with worsened rates of OS when patients had stages IA to IIA (P=.009) and T2 stage tumors (P=.012) but not in either T1 stage or advanced stage IIB to IVB tumors.16 In contrast, a study by Su et al18 evaluating patients with MF from the National Cancer Database found that patients with MF originating in the head and neck region had similar survival compared with MF originating in the lower limbs after pairwise propensity matching. It previously has been postulated that primary MF lesions originating in the head and neck region have relatively higher frequencies of biological markers believed to be associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and poorer prognosis, such as histopathologic folliculotropism, T-cell receptor gene rearrangements, and large-cell transformations.16 However, MF typically is an indolent disease with advanced-stage MF following an aggressive disease course that often is refractory to treatment. A review from a single academic center noted that 5-year DSS was 97.3% for T1a but only 37.5% for T4.23 Similarly, a meta-analysis evaluating survival in patients with MF noted the 5-year OS for stage IB was 85.8% while for stage IVB it was only 23.3%.24 As such, having advanced-stage MF influences survival to a far greater extent than the presence of head and neck involvement alone. Accordingly, the significantly higher prevalence of advanced T stage disease and increased likelihood of lymph node involvement in MF lesions originating in the head and neck region (both P<.001) may explain why previous studies noted a poorer survival rate with head and neck involvement, as they did not have the sample size to adjust for these factors. Controlling for the above factors likely explains the nonsignificance of this region as a prognostic indicator in our multivariate analysis of OS and DSS.