Approximately 108 million individuals have been forcibly displaced across the globe as of 2022, 35 million of whom are formally designated as refugees.1,2 The United States has coordinated resettlement of more refugee populations than any other country; the most common countries of origin are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Afghanistan, and Myanmar.3 In 2021, policy to increase the number of refugees resettled in the United States by more than 700% (from 15,000 up to 125,000) was established; since enactment, the United States has seen more than double the refugee arrivals in 2023 than the prior year, making medical care for this population increasingly relevant for the dermatologist.4

Understanding how to care for this population begins with an accurate understanding of the term refugee. The United Nations defines a refugee as a person who is unwilling or unable to return to their country of nationality because of persecution or well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This term grants a protected status under international law and encompasses access to travel assistance, housing, cultural orientation, and medical evaluation upon resettlement.5,6

The burden of treatable dermatologic conditions in refugee populations ranges from 19% to 96% in the literature7,8 and varies from inflammatory disorders to infectious and parasitic diseases.9 In one study of 6899 displaced individuals in Greece, the prevalence of dermatologic conditions was higher than traumatic injury, cardiac disease, psychological conditions, and dental disease.10

When outlining differential diagnoses for parasitic infestations of the skin that affect refugee populations, helpful considerations include the individual’s country of origin, route traveled, and method of travel.11 Parasitic infestations specifically are more common in refugee populations when there are barriers to basic hygiene, crowded living or travel conditions, or lack of access to health care, which they may experience at any point in their home country, during travel, or in resettlement housing.8

Even with limited examination and diagnostic resources, the skin is the most accessible first indication of patients’ overall well-being and often provides simple diagnostic clues—in combination with contextualization of the patient’s unique circumstances—necessary for successful diagnosis and treatment of scabies and pediculosis.12 The dermatologist working with refugee populations may be the first set of eyes available and trained to discern skin infestations and therefore has the potential to improve overall outcomes.

Some parasitic infestations in refugee populations may fall under the category of neglected tropical diseases, including scabies, ascariasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and schistosomiasis; they affect an estimated 1 billion individuals across the globe but historically have been underrepresented in the literature and in health policy due in part to limited access to care.13 This review will focus on infestations by the scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis) and the human louse, as these frequently are encountered, easily diagnosed, and treatable by trained clinicians, even in resource-limited settings.

Scabies

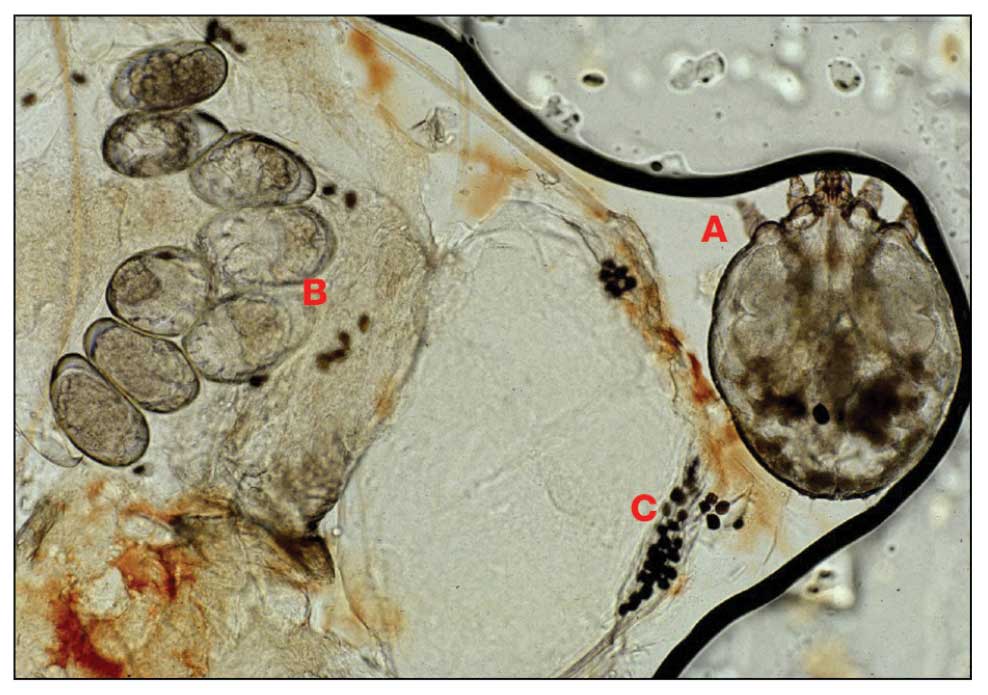

Scabies is a parasitic skin infestation caused by the 8-legged mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The female mite begins the infestation process via penetration of the epidermis, particularly the stratum corneum, and commences laying eggs (Figure 1). The subsequent larvae emerge 48 to 72 hours later and remain burrowed in the epidermis. The larvae mature over the next 10 to 14 days and continue the reproductive cycle.14,15 Symptoms of infestation occurs due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite and its by-products.16 Transmission of the mite primarily occurs via direct (skin-to-skin) contact with infected individuals or environmental surfaces for 24 to36 hours in specific conditions, though the latter source has been debated in the literature.