To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

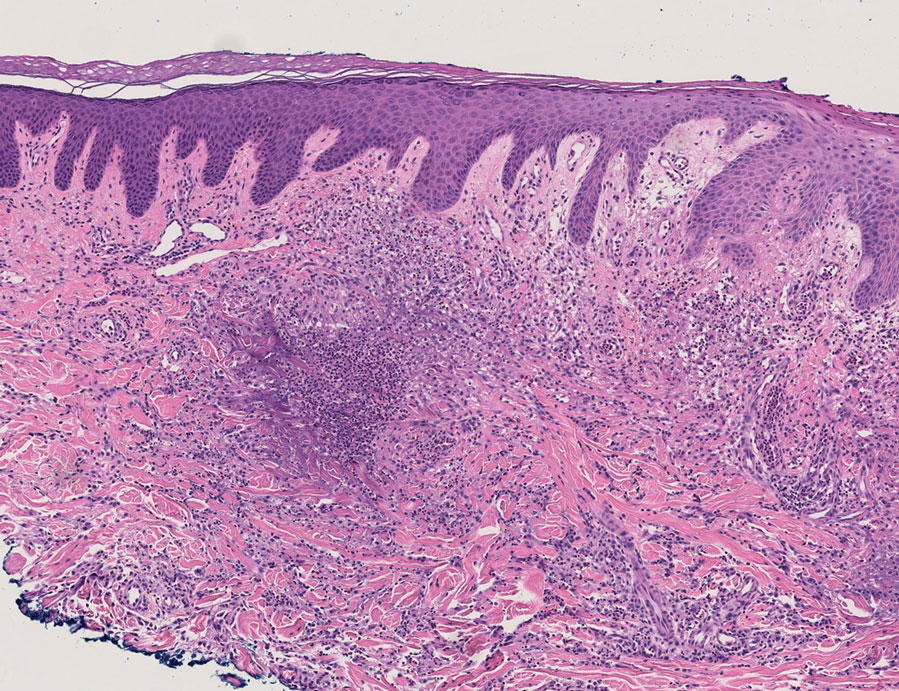

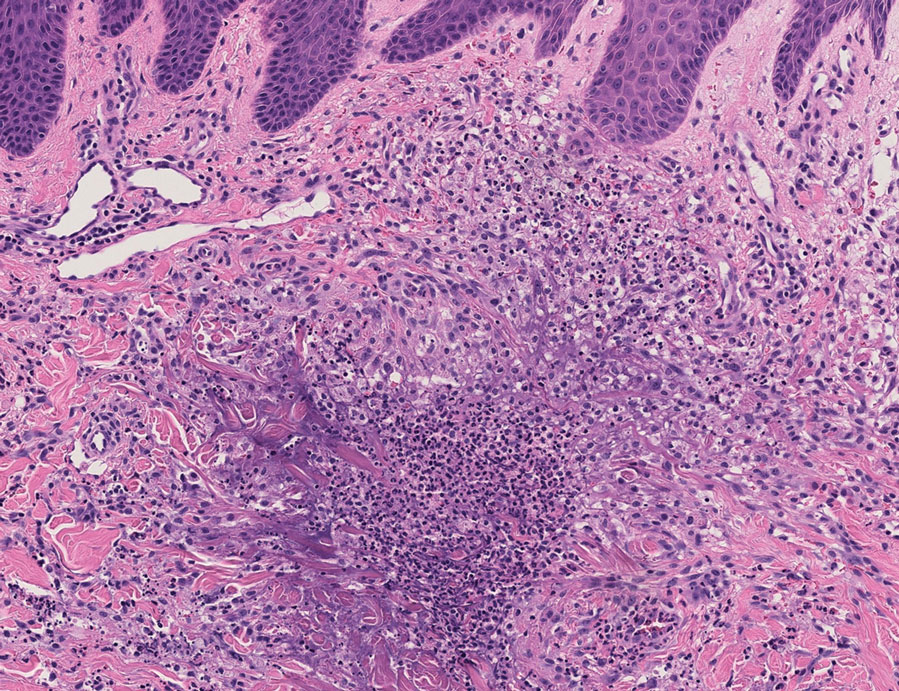

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

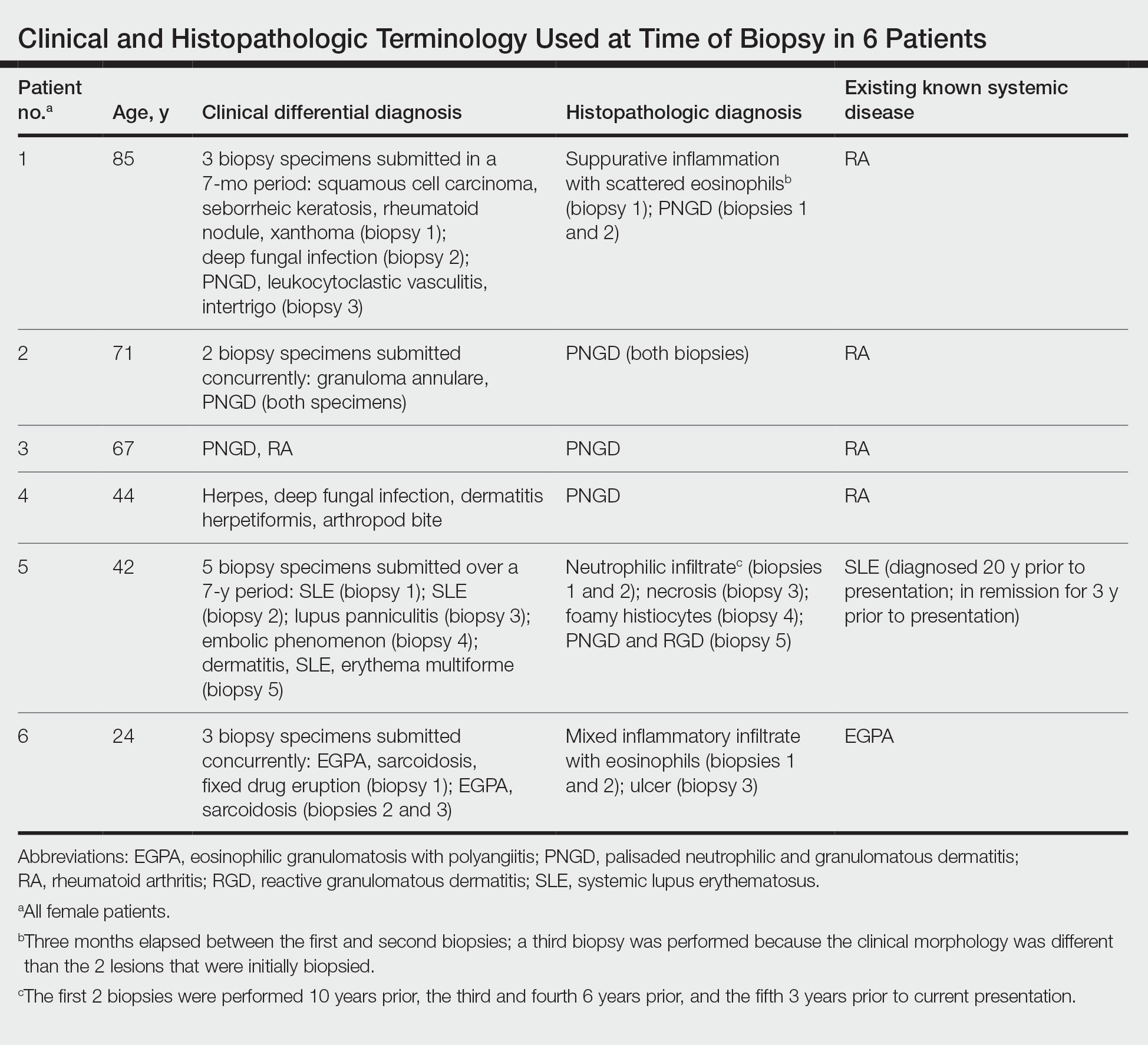

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1