To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

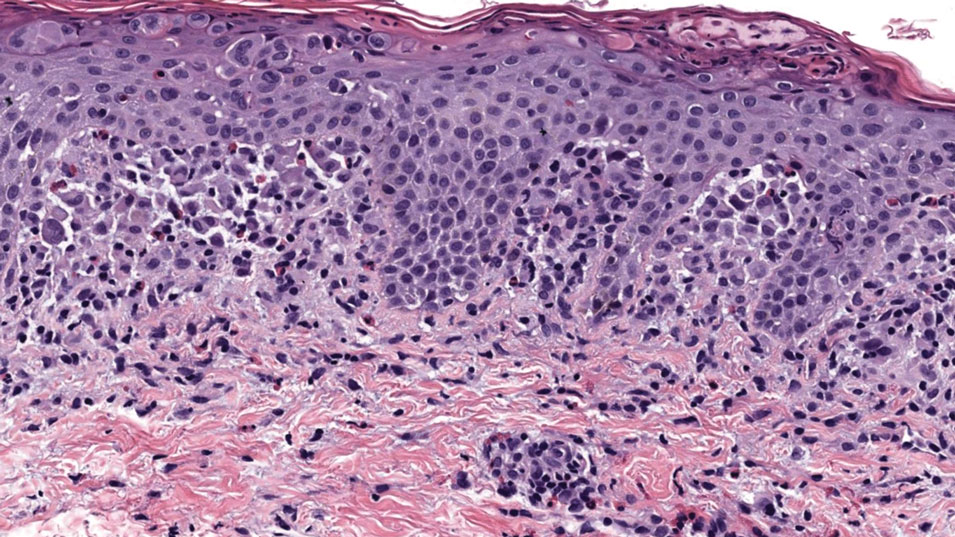

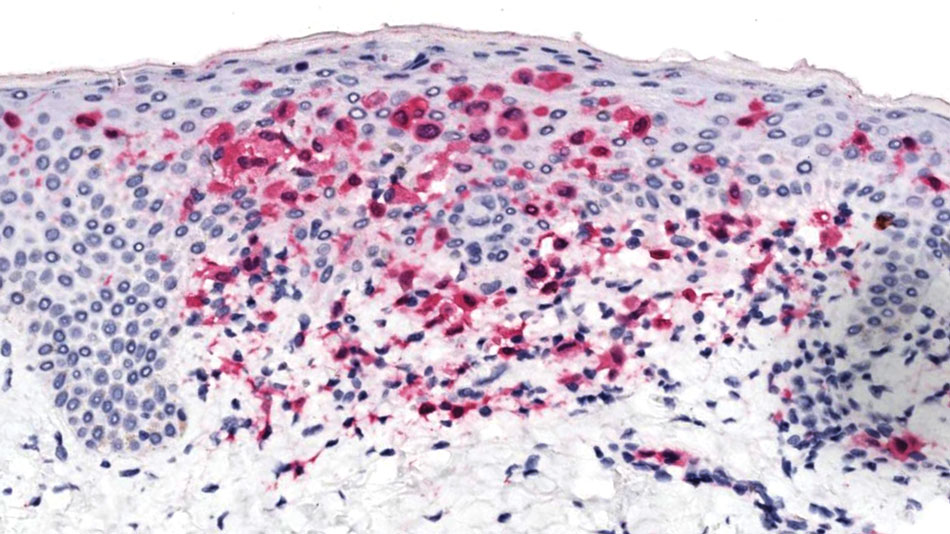

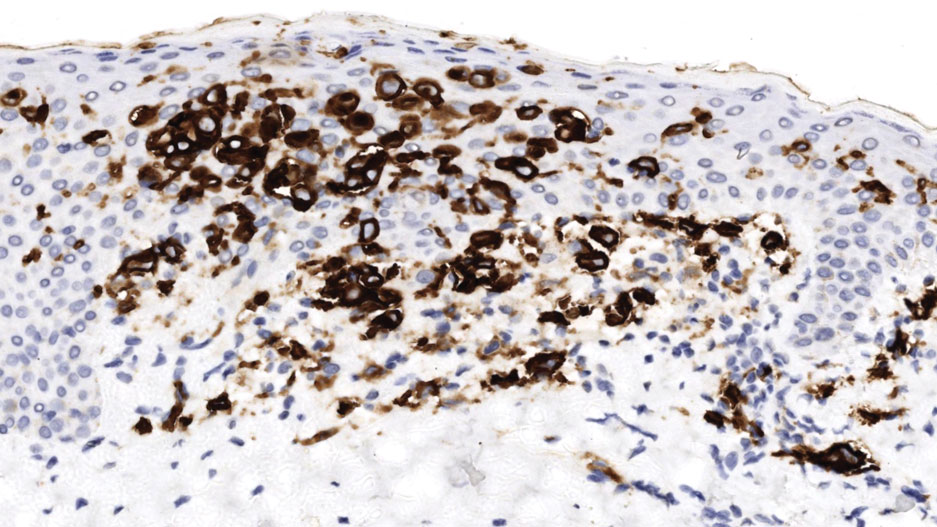

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

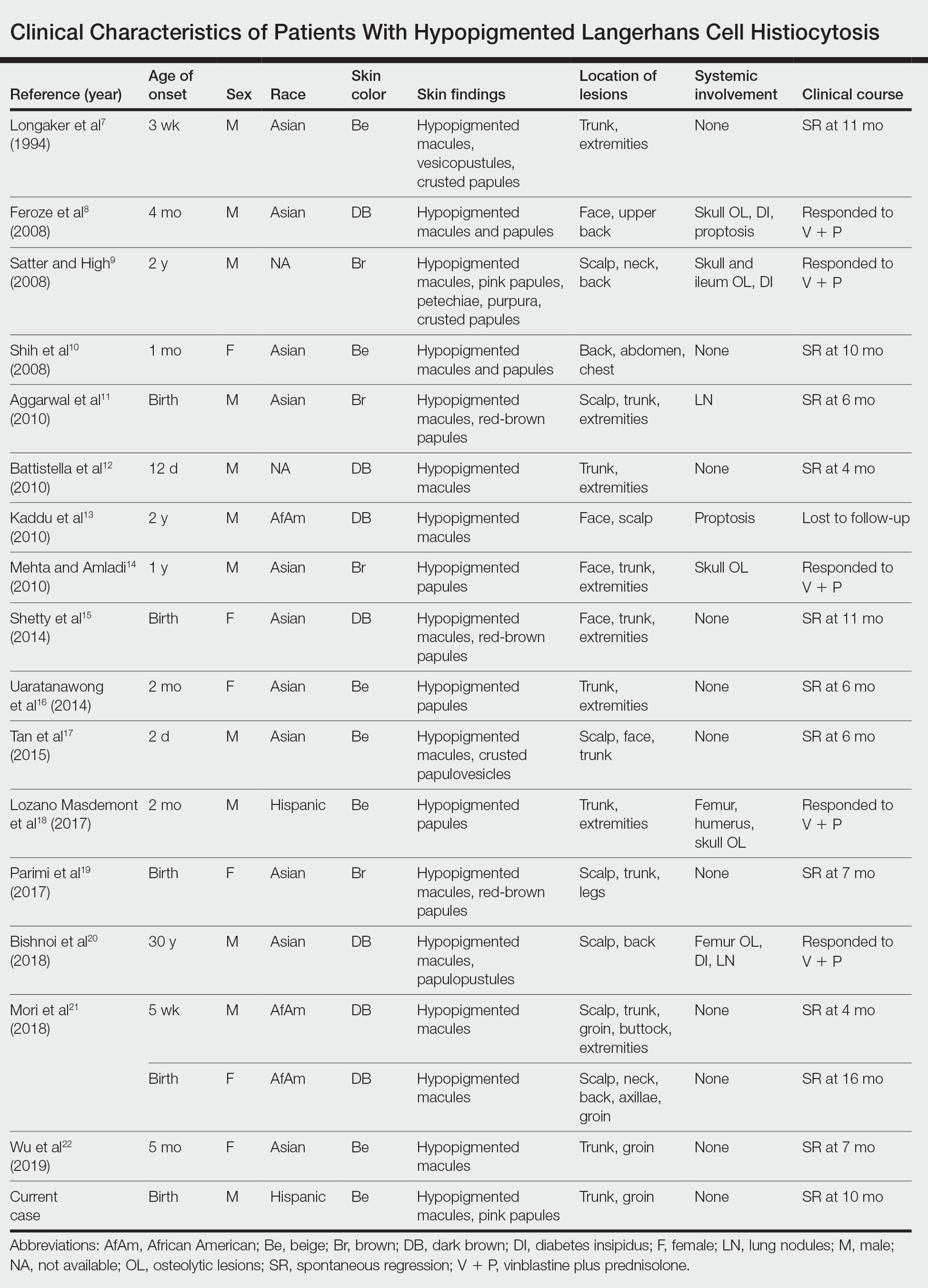

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.