Prurigo nodularis (PN)(also called chronic nodular prurigo, prurigo nodularis of Hyde, or picker’s nodules) was first characterized by James Hyde in 1909.1-3 Prurigo nodularis manifests with symmetrical, intensely pruritic, eroded, or hyperkeratotic nodules or papules on the extremities and trunk.1,2,4,5 Studies have shown that individuals with PN experience pruritus, sleep loss, decreased social functioning from the appearance of the nodules, and a higher incidence of anxiety and depression, causing a negative impact on their quality of life.2,6 In addition, the manifestation of PN has been linked to neurologic and psychiatric disorders; however, PN also can be idiopathic and manifest without underlying illnesses.2,6,7

Prurigo nodularis has been associated with other dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis (up to 50%), lichen planus, keratoacanthomas (KAs), and bullous pemphigoid.7-9 It also has been linked to systemic diseases in 38% to 50% of cases, including chronic kidney disease, liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, malignancies (hematopoietic, liver, and skin), and HIV infection.6,8,10

The pathophysiology of PN is highly complex and has yet to be fully elucidated. It is thought to be due to dysregulation and interaction of the increase in neural and immunologic responses of proinflammatory and pruritogenic cytokines.2,11 Treatments aim to break the itch-scratch cycle that perpetuates this disorder; however, this proves difficult, as PN is associated with a higher itch intensity than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.10 Therefore, most patients attempt multiple forms of treatment for PN, ranging from topical therapies, oral immunosuppressants, and phototherapy to the newest and only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of PN—dupilumab.1,7,11 Herein, we provide an updated review of PN with a focus on its epidemiology, histopathology and pathophysiology, comorbidities, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and current treatment options.

Epidemiology

There are few studies on the epidemiology of PN; however, middle-aged populations with underlying dermatologic or psychiatric disorders tend to be impacted most frequently.2,12,13 In 2016, it was estimated that almost 88,000 individuals had PN in the United States, with the majority being female; however, this estimate only took into account those aged 18 to 64 years and utilized data from IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (IBM Watson Health) from October 2015 to December 2016.14 More recently, a retrospective database analysis estimated the prevalence of PN in the United States to be anywhere from 36.7 to 43.9 cases per 100,000 individuals. However, this retrospective review utilized the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code; PN has 2 codes associated with the diagnosis, and the coding accuracy is unknown.15 Sutaria et al16 looked at racial disparities in patients with PN utilizing data from TriNetX and found that patients who received a diagnosis of PN were more likely to be women, non-Hispanic, and Black compared with control patients. However, these estimates are restricted to the health care organizations within this database.

In 2018, Poland reported an annual prevalence of 6.52 cases per 100,000 individuals,17 while England reported a yearly prevalence of 3.27 cases per 100,000 individuals.18 Both countries reported most cases were female. However, these studies are not without limitations. Poland only uses the primary diagnosis code for medical billing to simplify clinical coding, thus underestimating the actual prevalence; furthermore, clinical codes more often than not are assigned by someone other than the diagnosing physician, leaving room for error.17 In addition, England’s PN estimate utilized diagnosis data from primary care and inpatient datasets, leaving out outpatient datasets in which patients with PN may have been referred and obtained the diagnosis, potentially underestimating the prevalence in this population.18

In contrast, Korea estimated the annual prevalence of PN to be 4.82 cases per 1000 dermatology outpatients, with the majority being men, based on results from a cross-sectional study among outpatients from the Catholic Medical Center. Although this is the largest health organization in Korea, the scope of this study is limited and lacks data from other medical centers in Korea.19

Histopathology and Pathophysiology

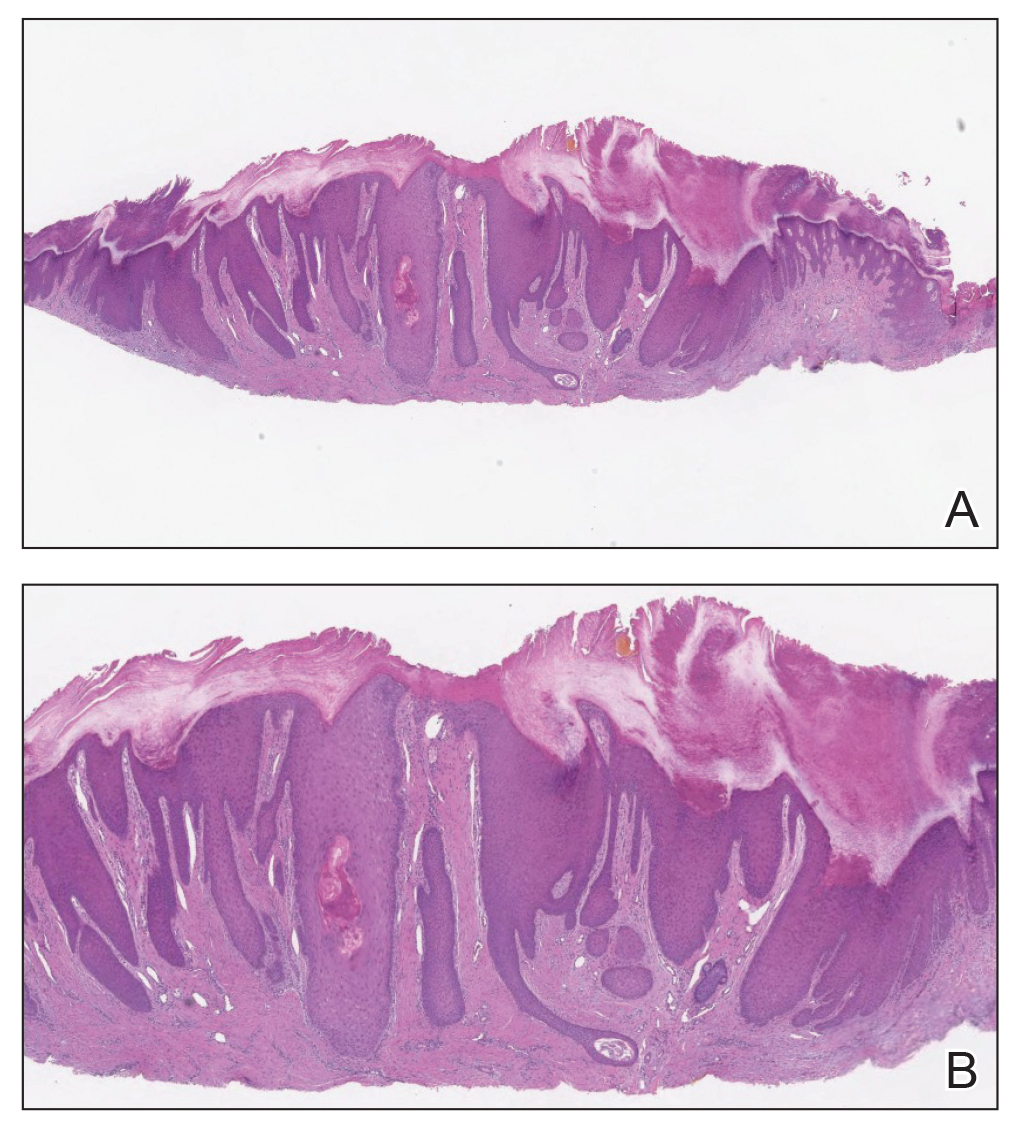

Almost all cells in the skin are involved in PN: keratinocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, collagen fibers, and nerve fibers.11,20 Classically, PN manifests as a dome-shaped lesion with hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with increased thickness of the papillary dermis consisting of coarse collagen with compact interstitial and circumvascular infiltration as well as increased lymphocytes and histocytes in the superficial dermis (Figure 1).20 Hyperkeratosis is thought to be due to either the alteration of keratinocyte structures from scratching or keratinocyte abnormalities triggering PN.21 However, the increase in keratinocytes, which secrete nerve growth factor, allows for neuronal hyperplasia within the dermis.22 Nerve growth factor can stimulate keratinocyte proliferation23 in addition to the upregulation of substance P (SP), a tachykinin that triggers vascular dilation and pruritus in the skin.24 The density of SP nerve fibers in the dermis increases in PN, causing proinflammatory effects, upregulating the immune response to promote endothelial hyperplasia and increased vascularization.25 The increase in these fibers may lead to pruritus associated with PN.2,26

Many inflammatory cytokines and mediators also have been implicated in PN. Increased messenger RNA expression of IL-4, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-31 has been described in PN lesions.3,27 Furthermore, studies also have reported increased helper T cell (TH2) cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13, in the dermis of PN lesions in patients without a history of atopy.3,28 These pruritogenic cytokines in conjunction with the SP fibers may create an intractable itch for those with PN. The interaction and culmination of the neural and immune responses make PN a complex condition to treat with the multifactorial interaction of systems.