Case

A 64-year-old man presented to the ED seeking assistance in withdrawing from his prescription of oxycodone, which he had been taking to manage chronic pain due to rheumatoid arthritis. He stated that he had discontinued the oxycodone approximately 4 days prior to presentation and over the past 3 days, had been experiencing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and diaphoresis. He noted that his symptoms were identical to those he had during previous unsuccessful attempts to wean himself from the narcotic medication. He denied any fever, dysuria, penile discharge, or any skin changes. Further evaluation revealed a remote history of a cholecystectomy and an appendectomy.

During the initial examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. His vital signs were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; blood pressure, 107/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate, 22 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The abdominal examination revealed moderate diffuse tenderness, mild distension without guarding or rebound, and some well-healed surgical scars.

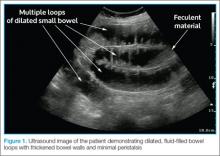

Based on the patient’s abnormal abdominal examination and history of abdominal surgeries, a bedside ultrasound was performed prior to any laboratory testing or other imaging studies. A curvilinear probe in the abdominal mode setting was used to scan all four quadrants of the abdomen, assessing both the sagittal and transverse planes. The ultrasound revealed dilated, fluid-filled bowel loops with thickened bowel walls, as well as minimal peristalsis (Figure 1).In light of the abnormal sonographic findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of a distal small bowel obstruction (SBO). Surgery services were consulted. As the patient’s current symptoms were believed to be the result of an SBO and not from narcotic withdrawal, surgery services instructed nothing by mouth and elected nonsurgical management. They placed a nasogastric tube and administered fluids and analgesics via IV. The patient was discharged 4 days after presentation to the ED, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Annually in the United States, less than 1% of all patients presenting to EDs are subsequently diagnosed with SBO.1 However, this disease comprises 15% of all surgical hospital admissions, costing upward of $1 billion in annual hospital charges.2 Moreover, patients with SBO suffer from a disproportionately high morbidity (eg, bowel strangulation, necrosis) and mortality than the general population,3-5 and delayed diagnosis is associated with a higher risk of bowel resection. One study by Bickell et al6 showed that only 4% of patients appropriately managed less than 24 hours after symptom onset required resection compared with 10% to 14% of patients managed more than 24 hours after symptom onset.

As most patients diagnosed with SBO are first seen in the ED, emergency physicians (EPs) have a distinctive role in lowering the likelihood of a poor outcome by making this diagnosis early.7 Multiple methods of diagnosing SBO are at the disposal of the clinician, including the history and physical examination, abdominal X-ray, ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The history and physical examination can be rapidly performed at the bedside in patients with suspected SBO. The factors typically associated with SBO include constipation, a previous history of abdominal surgeries, abnormal bowel sounds, and abdominal distension.3 However, these findings are not sufficient to accurately and adequately rule in or rule out disease.3,8,9

Diagnostic Imaging

While patient history and physical examination may be helpful in diagnosing SBO, imaging plays a critical role in the definitive diagnosis. The imaging modality that is the de facto gold standard for diagnosis is the CT scan.10 A meta-analysis by Taylor et al,3 which included 64-slice multidetector CT imaging studies (using both oral and IV contrast), demonstrated sensitivities of 93% to 96% and specificities of 93% to 100% in diagnosing SBO.

In patients in whom CT is contraindicated, MRI can be a useful alternative, with studies showing a similar diagnostic accuracy to 64-slice CT.13,14 Both CT and MRI are highly accurate in diagnosing SBO; however, there are disadvantages to their use. Such disadvantages include the inability to perform these studies at bedside; the length of time to perform these studies; the higher cost compared to other modalities; and, in CT, the adverse side effects of radiation and possible contrast reactions.

Bedside Ultrasound

Abdominal X-ray traditionally has been the initial choice in bedside imaging for SBO; however, a recent meta-analysis found this modality to have a summary sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 66%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.6, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.43 in diagnosing SBO.3 Based on these statistics, bedside ultrasound has recently ascended as a viable alternative to abdominal X-ray.