Symptoms in MSCC at presentation can be motor, sensory, and/or autonomic. Back pain varies depending on the site of metastasis, which can be referred, local, radicular, or a combination of all three.18 The primary complaint is pain in 83% to 96% of cases,19,20 though this is a nonspecific sign.

Back pain is typically experienced for a median of 62 days prior to treatment of MSCC, usually due to considerable delays in diagnosis and treatment21; patients presenting with radiculopathy are usually symptomatic an average of 9 weeks prior to diagnosis.22 Tenderness is often present over the affected area and, as with mechanical back pain, pain associated with MSCC may worsen with loads, which bear pressure on the vertebral column.23 In contrast to mechanical back pain, rest in a supine position frequently exacerbates pain in MSCC,17 often disrupting sleep. In addition, weakness follows pain with an estimated 35% to 85% of patients endorsing the symptom.24Previous studies have shown 40% to 64% of patients were not ambulatory at the time of diagnosis.19,25 Recent case series, however, report an increased number of ambulatory patients—possibly due to increased clinician awareness.26 In other cases, only 9% of patients were able to walk independently without aid.27 Loss of sensation, dense paraplegia, and incontinence are late findings and likely signal some degree of permanent disability.19

Misdiagnosis is a common issue in the ED setting. In an interesting retrospective study of 63 patients with spinal cord compression28 (not necessarily malignant), 18 (29%) were misdiagnosed.28 Consequently, there was a significant delay in diagnosis despite obvious neurological deficits at presentation.

Evaluation and Imaging

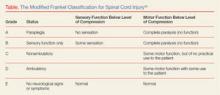

A detailed physical examination is essential to diagnosing MSCC. A thorough neurological examination, including sensation, strength, and reflexes should be carefully documented. If spinal instability is suspected, range-of-motion testing is contraindicated. The modified Frankel classification,29 adapted from the traumatic spine cord injury work by Frankel, et al,30 may be used to assess the degree of disability (Table).

Lu et al11 noted hyperreflexia and upward going Babinski reflex as common findings. Moreover, risk factors of decreased rectal sphincter tone and bladder were determinant for poor outcomes.

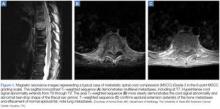

Incidental discovery of MSCC on imaging in the absence of neurological findings is rare. Approximately 26% to 29% of total metastatic deposits are occult and not visible on X-ray.4,10 Prior to the 1990s, spinal cord compression was diagnosed by my elography.31 Fortunately, this uncomfortable procedure has been replaced by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1).32 While gadolinium-enhanced MRI can help to determine intradural tumor or leptomeningeal disease, it is not required for cord compression studies. Unenhanced MRI is equal to myelography in detecting epidural disease and is more sensitive at detecting vertebral metastasis,33 justifying its use and reducing procedure time compared to gadolinium-enhanced studies.MRI studies should include the entire spine—not just the perceived area of interest— as up to 38% of patients have multiple-site metastases12 (Figure 1). Sensory deficits and mechanical pain may be present two to four vertebral levels away from the actual lesion.11 If MRI suggests cord compression, severity can be graded using the MSCC scale34 (Figure 2). Several scoring systems have been developed to aid in decision making concerning surgical treatment.

Management and Outcomes

The goal of therapy is symptom control and preservation of function. This requires a multidisciplinary approach and may involve radiation therapy and surgery, as well as medical efforts. Upon diagnosis and initiation of therapy, serial neurological evaluation should be undertaken. Neurovital signs should be scheduled to coincide with other nursing efforts to ease the burden of care and minimize patient discomfort.

The mainstay of medical therapy is treatment with corticosteroids.35 Initial trials have demonstrated that corticosteroids improve functional status in MSCC, but controversy exists regarding the effective dose. In a randomized, controlled trial by Sorensen et al,36 which sought to evaluate functional outcomes of highdose corticosteroids as an adjunct to radiotherapy, 57 patients received either high-dose dexamethasone or no corticosteroid therapy. Fifty-nine percent of patients in the dexamethasone group were ambulatory 6 months after treatment compared to 39% in the group who did not receive steroids.36

The use of high-dose corticosteroids was once a common practice, but is no longer considered standard of care and should be avoided based on increased side effects with no improvement in outcome compared with low-dose corticosteroids. 37 At our institution, moderate doses of corticosteroids are recommended concomitantly with radiation therapy or/and surgery. Our patients generally receive 10 mg of dexamethasone as a loading dose, followed by 16 mg daily in divided doses. Gastrointestinal (GI) prophylaxis should be initiated to reduce GI tract toxicity, and special attention should be given to glucose control in patients with diabetes.