What is the diagnosis?

Is additional imaging necessary, and if so, why?

An 83-year-old woman with history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presents to the ED with epigastric abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was obtained; a coronal reformatted image is shown above (Figure 1).

Answer

Mirizzi syndrome, partial obstruction of the common hepatic duct by a large gallstone at the gallbladder neck (as in this patient) or within the cystic duct, was first described by Argentinian surgeon Pablo Mirizzi in the mid-20th century. Although Mirizzi syndrome occurs in less than 3% of all patients with cholelithiasis, the inflammation and fibrosis associated with this condition can lead to cholecystobiliary or choledochobiliary fistula formation. Preoperatively unrecognized cases are associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared with uncomplicated cholelithiasis. Cholecystectomy in patients with Mirizzi syndrome is often performed via an open rather than laparoscopic approach, and biliary fistula may require surgical repair with choledochoduodenostomy. 1-3

The recommended initial imaging modality for patients with clinical signs of biliary obstruction (eg, jaundice and/or intermittent cholangitis) is right upper quadrant ultrasound based on its greater sensitivity for gallstone detection compared to CT and wider availability than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If ultrasound demonstrates central biliary ductal prominence with calculi at the gallbladder neck and/or cystic duct, further noninvasive imaging with MRI/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be considered to evaluate for Mirizzi syndrome, as well as to exclude more distal common bile duct obstruction/stricture that may not be visible sonographically.

Based on this patient’s nonspecific epigastric pain, CT imaging was evaluated before ultrasound. While the CT findings and elevated liver function tests suggested Mirizzi syndrome, MRCP was subsequently performed to better characterize the partial biliary obstruction, evaluate for biliary fistula, and exclude noncalcified stones within the biliary tree.

The coronal CT image demonstrates two calcified stones within the gallbladder—a large stone more superiorly at the gallbladder neck and a smaller stone more inferiorly at the gallbladder fundus (black arrows, Figure 2)—with diffuse gallbladder wall thickening/ edema, suspicious for acute cholecystitis. Focal narrowing of the common hepatic duct (white arrow, Figure 2) was caused by the larger stone as it crosses the gallbladder neck with postobstructive dilatation of the more proximal/superior aspect of the common hepatic duct (yellow arrow, Figure 2).

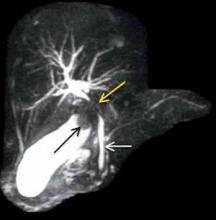

Maximum intensity projection from MRCP reveals the large gallstone at the gallbladder neck as a filling defect (black arrow, Figure 3), with focal compression of the adjacent common hepatic duct (yellow arrow, Figure 3). The more downstream common bile duct (white arrow, Figure 3) is of normal caliber without filling defect. Coronal single-shot fast spin echo image from the same examination again demonstrates narrowing of the common hepatic duct with associated upstream prominence of the central hepatic bile ducts (white arrow, Figure 4).

Given her advanced age, comorbidities, and lowimaging suspicion for biliary fistula, the patient in this case underwent successful laparoscopic, rather than open, cholecystectomy without complication.