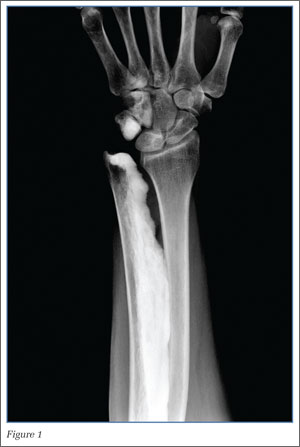

Radiographs of the left wrist demonstrated cortically based sclerosis of the ulna, triquetrum, and hamate; no fracture or dislocation was seen. This pattern of cortical bone formation, described as the “dripping candle wax” sign, is characteristic for melorheostosis, a rare nonhereditary mixed sclerosing bone dysplasia.

Sclerosing bone dysplasias include a wide range of both hereditary and nonhereditary skeletal abnormalities that result from a disturbance in the bone ossification pathway. These dysplasias can be categorized as disruptions in endochondral bone formation, disruptions in intramembranous bone formation, or mixed. First described by Leri and Joanny in 1922, there have been approximately 400 reported cases of melorheostosis since its initial identification.1,2

In melorheostosis, the distribution of lesions follows sclerotomes, skeletal regions supplied by a single spinal sensory nerve. The condition manifests as cortical and medullary hyperostosis involving one side of the bone (eg, medial or lateral) with a clear distinction between affected bone and the adjacent normal bone. As in this case, the radiographic appearance of melorheostosis is almost always sufficient for diagnosis.

Melorheostosis has no gender predilection and is usually diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood.5 While the etiology is unknown, genetic analyses have found a common loss-of-function mutation on chromosome 12q (LEMD3) associated with several sclerosing bone dysplasias, including melorheostosis, suggesting a common etiology.3 In addition, since melorheostosis typically has a sclerotomal distribution, some theories postulate that it represents an acquired defect of the spinal sensory nerves.1

Patients generally present with pain, stiffness, and occasionally joint swelling in the involved regions. Although any bone can be involved, the extremities are most often affected, with the disease frequently polyostotic, but rarely bilateral.4,5 In hyperostosis involving a joint, muscular atrophy, tendon and ligament shortening, and muscle contractures may be seen, which can limit range of motion.6 Some cases of leg-length discrepancy have also been described. Skeletal lesions may progress, but there is no reported risk of pathological fracture or malignant degeneration.7

Treatment is dependent on the patient’s age, location of involved bone, and specific symptoms. The major goals of treatment are pain relief and preserving or restoring full range of motion. Therapy is generally focused on conservative techniques such as analgesics, braces, and physical therapy. Occasionally, surgical treatment is necessary, including soft-tissue release, fasciotomy, tendon lengthening, and arthroplasty.8

In the ED setting, it is important to recognize melorheostosis as the source of pain as this condition may be confused with osseous neoplasm. Based on this patient’s underlying partially treated MS flare and the potential for recurring fall, admission was recommended for intravenous corticosteroids. The patient, however, was only amenable to a wrist splint and refused further treatment.

Dr Escalon is second-year postgraduate resident, the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Dr Loftus is an assistant professor of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.