Case

A 12-year-old boy presented to the ED via emergency medical services after he was struck by motor vehicle while skateboarding without a helmet or other safety equipment. He was thrown approximately 10 feet, but experienced no loss of consciousness, pain, or active bleeding at the site of the accident. Unaccompanied by family, he arrived to the ED fully immobilized on a long back board. His field vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP), 100/65 mm Hg; heart rate (HR) 105 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The patient had an estimated Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 14, with one point removed due to confusion.

Primary examination showed an intact airway with equal breath sounds bilaterally, and pulses were equal in all extremities with audible heart sounds. The patient was able to move all extremities, and showed no obvious deformities or bleeding. He was neurologically intact, with equal strength and sensation. He did, however, elicit some confusion during the examination, continuously stating it was “all his fault” and asking the medical staff where he was. This confusion persisted even after repeated reorientation. His vital signs remained stable, with slight tachycardia (BP, 105/67 mm hg; HR 100 beats/minute; RR, 17 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile; pulse oxygen saturation, 99%). An abbreviated history revealed no allergies, medications, or past medical history. When questioned, the patient had no recollection of the accident or the last time he had eaten.

A secondary survey was significant for a small contusion/abrasion on the patient’s forehead but an otherwise normal head, ear, eyes, nose, and throat examination and no cervical c-spine tenderness. The patient denied any chest wall tenderness, but there was a dramatic palpable defect in the right chest wall, with profound asymmetry when compared to the left chest wall. No sharp, bony edges could be palpated, nor could any crepitance be felt. Breath sounds were reexamined and remained equal and nonlabored, and the patient continued to have a stable oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The rest of the secondary survey was negative, and c-spine, pelvic, and portable chest X-rays were all negative for acute findings.

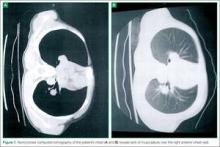

Due to the physical examination findings on the chest wall, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed with contrast (Figure). The chest CT was normal, except for a lack of musculature over the right anterior chest wall. The patient’s mother arrived shortly after imaging studies, at which time he was reexamined. When interviewing his mother for further history, she stated that her son had been diagnosed with mild Poland Syndrome as a child, and that he has always had a chest deformity. All other studies, including a noncontrast CT of the brain, were normal. The child quickly improved during his 6-hour observation in the ED, and he was subsequently discharged home with the diagnosis of a concussion.

Discussion

Poland syndrome, also known as hand and ipsilateral thorax syndrome, is a rare congenital disorder with unknown etiology.1,2 The condition was first officially described in 1841 by Alfred Poland at Guy’s Hospital in London, though reports exist as early as 1826. Poland, a medical student, made the discovery while examining the cadaver of a hanged convict.

The occurrence of Poland syndrome is estimated to be from 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 75,000 to 100,000 by some reports,1-4 with a higher incidence in males than females (3:1 ratio) and 75% right-sided dominance.2 The syndrome is primarily described as unilateral, but there is one case report of suspected bilateral involvement.1 The components of the syndrome consist of aplasia of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle, hypoplasia of the pectoralis minor muscle, decreased development of breast and subcutaneous tissue, and a variety of ipsilateral hand abnormalities, including shortened carpels and phalanges, and syndactyly. The syndrome is quite variable, with different individuals eliciting combinations of the above components.

Poland syndrome was initially believed to be a nonfamilial disorder due to its sporadic nature, as illustrated by a case report of an isolated affected identical twin.3 However, enough cases of familial involvement have been reported that there is a proposed theory of an inheritable trait. Although over 250 patients with this syndrome have been described, there is no clear cause.2 The current theory of etiology is felt to be due to a lack of blood flow in the subclavian artery, or one of its branches, early in the development of the fetus, around the end of the sixth week of development. Individuals can have mild to severe manifestations, ranging as mild (eg, only pectoralis involvement), to severe (eg, rib hypoplasia, complete absence of ipsilateral hand, dextrocardia, lung herniation). Case reports of high functioning athletes with the disorder show that there is not necessarily functional impairment.