Intravascular hemolysis in the presence of infection should prompt emergency physicians (EPs) to consider Clostridium perfringens septicemia and to act quickly to treat the infection. C perfringens septicemia is a rare, rapidly fatal disease with a reported mortality rate of at least 70%.1 Its expeditious lethality is due to a combination 7-minute doubling time of the organism and its production of a multitude of virulent toxins.1

This disease is deceptive: Patients may not appear to be severely ill and may be hemodynamically stable, not meeting systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, yet they rapidly decompensate. No interventions have been shown to reliably change outcome; however, the best hope for survival lays in early identification and definitive treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and surgical intervention for source control. The authors present a fatal ED case of massive acute intravascular hemolysis due to C perfringens septicemia, the result of a cryptic liver abscess.

Case

A 74-year-old man with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension was transferred from an outside hospital to a tertiary-care referral center for leukocytosis and hyperbilirubinemia, where he had presented with fatigue and jaundice. A year prior, he had a cholecystectomy complicated by accidental hepatic artery ligation necessitating biliary tract reconstruction, but had been well since that event.

At the outside hospital, blood tests revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 21.0 x 109/L and elevated values on liver function tests with an elevated indirect hyperbilirubinemia. A right upper quadrant ultrasound showed a poorly defined hyperechoic mass behind the liver, but no bile-duct dilation or stones.

On arrival, the patient’s vital signs were: temperature, 100.4°F; heart rate, 92 beats/minute; blood pressure, 187/98 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. An electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay with strain pattern. He was awake, comfortable, and conversant and oriented to place and person, but not to time. He was markedly jaundiced with scleral icterus, dry mucosal membranes, and foul breath. His neck was supple and nontender. His heart had a regular rate and rhythm, without murmur, rubs, or gallops, and his lungs were bilaterally clear to auscultation. The patient’s obese abdomen was soft and nontender, without rebound or guarding. He moved in a coordinated manner, and had no clonus or asterixis.

Repeat laboratory evaluation revealed a WBC of 32.2 x109/L, an elevated troponin level of 0.30 ng/mL, and an increased brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of 636.2 pg/mL. Prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR) were normal. The chemistry test was reported as hemolyzed. Blood samples were redrawn three additional times, but each time the laboratory reported that each sample appeared progressively more hemolyzed and they were unable to obtain testable serum (Figure 1).

During his ED workup, the patient became more pale and jaundiced and began to produce bright red urine. The authors suspected that his hemolyzed blood samples were not due to blood draw artifact, but to intravascular hemolysis. A review of the blood smear showed gram-positive positive bacilli and ghost cells, commonly observed in hemolysis. Repeat laboratory tests showed interval increases in partial thromboplastin time, PT, and INR, and a D-dimer value of 3,621 ng/mL. Fibrinogen could not be measured due to gross hemolysis.

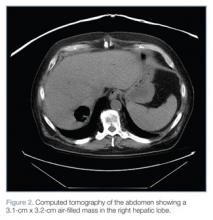

Empiric IV vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were administered, and computed tomography (CT) studies of the brain and abdomen were ordered. The CT of the brain was normal; however, CT of the abdomen revealed an air-filled abscess in the right hepatic lobe and air in the left hepatic lobe and biliary tree without biliary dilation or wall thickening (Figure 2).

After discussion with cardiology, the medical intensive care team, and general surgery services, the patient was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) with a plan to percutaneously drain the abscess the next morning.

Six and a half hours after arriving at the ED, the patient became acutely confused, tachypneic (RR, 22 breaths/minute) and tachycardic (HR, 102 beats/minute). On arrival to the SICU, he became unresponsive and pulseless. Resuscitation attempts were unsuccessful and the patient died.

Discussion

C perfringens is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus known for causing gas gangrene and is normally found in the human gastrointestinal (GI) and genital tracts. Individuals most at risk for C perfringens septicemia have underlying hepatobiliary or genitourinary tract disease, malignancy, immunosuppression, DM, or recent history of GI or genitourinary surgery.2,3

Hemolysis has been observed in 7% to 15% of C perfringens bacteremias.3 This is caused by C perfringens’ primary toxin, phospholipase C lecithinase (α-toxin), which splits lecithin in the red blood-cell membrane thereby damaging its structural integrity and causing hemolysis.4 Other virulent factors of C perfringens are β-, ε-, and τ- toxins, all of which cause capillary leakage by damaging the vascular endothelium.5