Switching HIV-infected children aged 3 and older from a recommended first-line antiretroviral treatment to efavirenz-based therapy may offer advantages, according to a new study in JAMA.

The study, based on a single-center open-label trial involving 298 South African children and published online Nov. 3, found that changing the HIV treatment regimen from ritonavir-boosted lopinavir-based therapy to efavirenz-based therapy was noninferior regarding rates of viral rebound and viral failure.

As a long-term maintenance treatment, efavirenz has several potential advantages over ritonavir-boosted lopinavir therapy. It requires once-daily rather than twice daily administration and doesn’t have the unpleasant taste of ritonavir-boosted lopinavir syrup, which would improve adherence and thus effectiveness. Efavirenz also may avoid some metabolic toxicities of the latter treatment and may simplify cotreatment for tuberculosis, a common coinfection among children with HIV in third-world countries. And it doesn’t require cold storage to maintain long-term stability, said Dr. Ashraf Coovadia of the University of the Witwatersrand and the Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, both in Johannesburg, and his associates.

There have been anecdotal reports of clinicians switching young pediatric patients to efavirenz, which is the recommended therapy for older children and adults, even though no data supported this practice until now. To shed light on the issue, the investigators compared the two treatment regimens in 298 children (average age, 4.3 years) who had been exposed to nevirapine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission and, after birth, had been maintained on ritonavir-boosted lopinavir-based therapy for an average of 3.5 years. A total of 148 of these children were randomly assigned to continue this recommended regimen and 150 were switched to efavirenz-based therapy; all were followed for 48 weeks.

Efavirenz-based therapy proved noninferior regarding both primary efficacy endpoints: viral rebound and viral failure. The probability of viral rebound, defined as more than 50 copies of HIV RNA per mL of plasma, was 17.6% for the efavirenz group and 28.4% for the ritonavir-boosted lopinavir group. The probability of viral failure, defined as more than 1,000 copies of HIV RNA per mL of plasma, was 2.7% and 2.0%, respectively. These data “support the safety and efficacy of switching to efavirenz,” Dr. Coovadia and his associates said (JAMA. 2015;314[17]:1808-17. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13631).

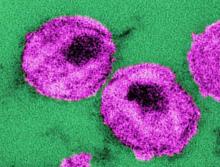

The lipid profiles of children taking efavirenz were better, with lower levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. CD4 cell counts and CD4 cell percentages remained in the normal range for both study groups, and there were no significant differences between the two in weight-for-age or height-for-age scores, rates of anemia or neutropenia, skin manifestations, or scores on a measure of emotional/behavioral problems. Alanine aminotransferase elevations were more common with efavirenz, as was nausea.

The adverse neuropsychiatric effects of efavirenz are well-known. After 4 weeks of treatment, 26% of children taking efavirenz had trouble sleeping or had nightmares, compared with no children in the other study group. However, this difference disappeared by 8 weeks. Two children developed seizure disorders presumed to be related to efavirenz. Both were found to have genetic mutations known to be associated with delayed drug clearance or abnormally high blood levels of efavirenz, and the seizures resolved after the drug was discontinued.