The good news for nonpregnant women who contract Zika infection is that the infection is not thought to pose any risk to future pregnancies. Currently, there is no evidence that a fetus conceived after maternal viremia has resolved would be at risk for infection. Still, many unanswered questions remain about Zika infection during pregnancy. For example, it’s currently unknown how often infection is transmitted from an infected mother to her fetus, or if infection is more severe at a particular point in gestation.

Although Zika virus has been isolated from breast milk, no infections have been linked to breastfeeding, and mothers are encouraged to continue to nurse, even in areas with widespread transmission. Infection with Zika at the time of birth or later in childhood has not been linked to microcephaly. Beyond that, the long-term health outcomes of infants and children with Zika virus infection are unknown.

“How far north do you think the virus will spread?” one mom asked me. “Do I need to be worried?”

For public health officials, that’s the sixty-four thousand dollar question. To date, there have been no cases acquired as a result of a mosquito bite in the United States, but the edge of the outbreak continues to creep north. Local transmission of the virus was reported in Cuba on March 14.

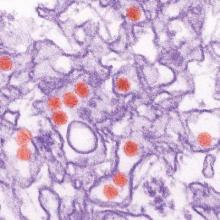

As of March 16, 2016, 258 travel-associated Zika virus cases have been diagnosed in the United States, including 18 in pregnant women. Six of these were sexually transmitted. Theoretically, “onward transmission” from one of these cases could occur if the right kind of mosquito bites an infected person during the period of active viremia and then bites someone else, transferring a tiny amount of the virus-contaminated blood.

According to CDC experts, “Texas, Florida, and Hawaii are likely to be the U.S. states with the highest risk of experiencing local transmission of Zika virus by mosquitoes.” Although this estimate is based on prior experience with similar viruses, the principal vector of Zika, Aedes aegypti, has been identified as far west as California and in a number of states across the South, including my home state of Kentucky. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes also have been proven competent vectors for Zika virus transmission and are more widely distributed throughout the continental United States.

In a thoughtful review published in JAMA Pediatrics, “What Pediatricians and Other Clinicians Should Know About Zika Virus,” Dr. Mark W. Kline and Dr. Gordon E. Schutze noted that up to two-thirds of the U.S. population live in an area where Aedes mosquitoes are present at least part of the year (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb 18. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0429). Fortunately, transmission of dengue and chikungunya, two other viruses carried by the same insect, is still very uncommon. Public health experts are urging individuals with Zika virus infection to avoid mosquito bites during the first week of illness, to protect others.

We should start now counseling our patients and families to avoid mosquito bites at home and abroad. Besides Zika virus, mosquitoes transmit several pathogens in the United States each year, including West Nile virus, LaCrosse encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and dengue.

Any collections of standing water should be eliminated, as these can be mosquito breeding grounds. These include flower pots, buckets, barrels, and discarded tires. The water in bird baths and pet dishes should be changed at least weekly, and children’s wading pools should be drained and stored on their side after use.

To the extent practical, exposed skin should be covered with long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks when individuals are in areas with mosquito activity. To enhance protection, clothing can be treated with permethrin, or pretreated clothing can be worn. An FDA-registered insect repellent should be applied to exposed skin, especially during hours of highest mosquito activity. Zika-carrying mosquitoes bite during the day, or dawn to dusk. Effective repellents include DEET, picaridin, IR3535, and oil of lemon eucalyptus, although families should read labels carefully as instructions for use vary, as does the recommended time period of reapplication. Combination sunscreen/insect repellent products are not recommended as repellent usually does not need to be reapplied as often as sunscreen. Parents also should be reminded not to use oil of lemon eucalyptus–containing products on children under 3 years of age.

“We’re going to get a lot more questions as the weather turns warmer,” said a colleague of mine. “I’m just waiting for the first call about a child who develops fever and a rash after a mosquito bite. Parents will wonder if it could be Zika.”