The care of women with female sexual disorders has made great strides since Masters and Johnson first began their study in 1957. In 2000, the Sexual Function Health Council of the American Foundation for Urologic Disease defined the classification system for female sexual dysfunction, which was eventually published and officially defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR.1 There are now definitions for sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorder, and sexual pain disorders.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) has complex physiologic and psychological components that require a detailed screening, history, and physical examination. Our goal in this review is to provide family physicians with insights and practical advice to help screen, diagnose, and treat female sexual dysfunction, which can have a profound impact on patients’ most intimate relationships.

Understanding the types of female sexual dysfunction

Most women consider sexual health an important part of their overall health.2 Factors that can disrupt normal sexual function include aging, socioeconomics, and other medical comorbidities. FSD is common in women throughout their lives and refers to various sexual dysfunctions including diminished arousal, problems achieving orgasm, dyspareunia, and low desire. Its prevalence is reported as high as 20% to 43%.3,4

The World Health Organization and the US Surgeon General have released statements encouraging health care providers to address sexual health during a patient’s annual visits.5 Unfortunately, despite this call to action, many patients and providers are initially hesitant to discuss these problems.6

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5) provides the definition and diagnostic guidelines for the different components of FSD. Its classification of sexual disorders was simplified and published in May 2013.7 There are now only 3 female dysfunctions as opposed to 5 in DSM-IV.

- Female hypoactive desire dysfunction and female arousal dysfunction were merged into a single syndrome labeled female sexual interest/arousal disorder.

- The formerly separate dyspareunia (painful intercourse) and vaginismus are now called genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

- Female orgasmic disorder remains as a category and is unchanged.

To qualify as a dysfunction, the problem must be present more than 75% of the time, for more than 6 months, causing significant distress, and must not be explained by a nonsexual mental disorder, relationship distress, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Substance- or medication-induced sexual dysfunction falls under “Other Dysfunctions” and is defined as a clinically significant disturbance in sexual function that is predominant in the clinical picture. The criteria for substance- and medication-induced sexual dysfunction are unchanged and include neither the 75% nor the 6-month requirement. The diagnosis of sexual dysfunction due to a general medical condition and sexual aversion disorder are absent from the DSM-5.7

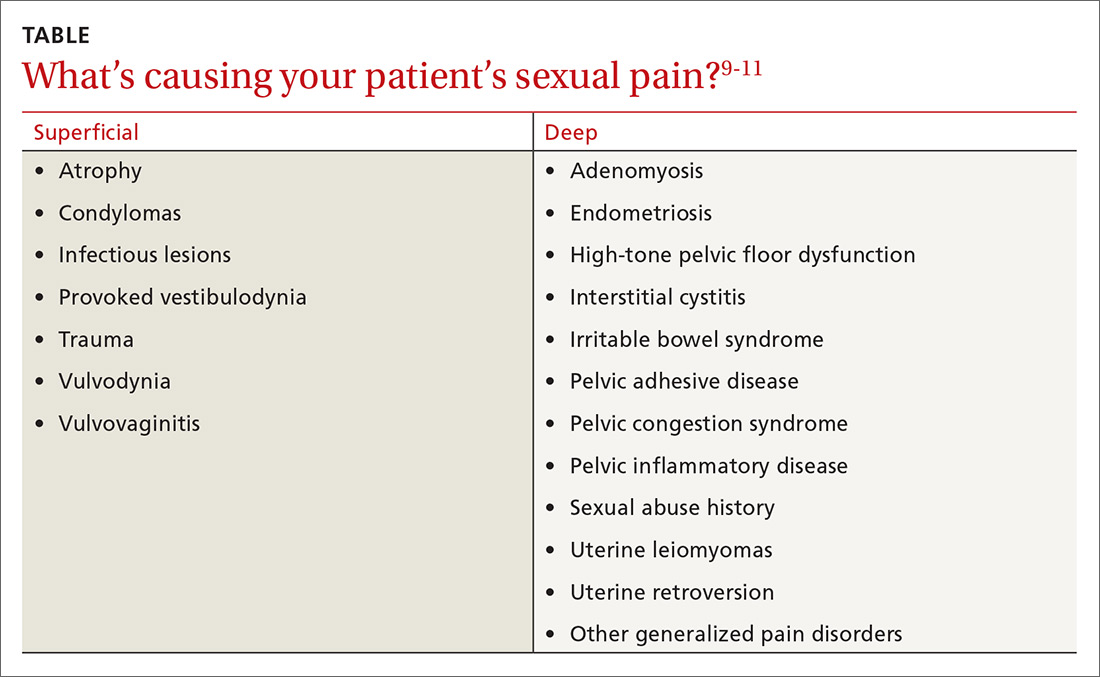

A common symptom. Female sexual disorders can be caused by several complex physiologic and psychological factors. A common symptom among many women is dyspareunia. It is seen more often in postmenopausal women, and its prevalence ranges from 8% to 22%.8 Pain on vaginal entry usually indicates vaginal atrophy, vaginal dermatitis, or provoked vestibulodynia. Pain on deep penetration could be caused by endometriosis, interstitial cystitis, or uterine leiomyomas.9

The physical examination will reproduce the pain when the vulva or vagina is touched with a cotton swab or when you insert a finger into the vagina. The differential diagnosis is listed in the TABLE.9-11

Evaluating the patient

Initially, many patients and providers may hesitate to discuss sexual dysfunction, but the annual exam is a good opportunity to broach the topic of sexual health.

Screening and history

Clinicians can screen all patients, regardless of age, with the help of a validated sex questionnaire or during a routine review of systems. There are many validated screening tools available. A simple, integrated screening tool to use is the Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women (BSSC-W), created by the International Consultation in Sexual Medicine.12 Although recommended by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,9 the BSSC-W is not validated. The questionnaire includes 4 questions that ascertain personal information regarding an individual’s overall sexual function satisfaction, the problem causing dysfunction, how bothersome the symptoms are, and if the patient is interested in discussing it with her provider.12

It’s important to obtain a detailed obstetric and gynecologic history that includes any sexually transmitted diseases, sexual abuse, urinary and bowel complaints, or surgeries. In addition, you’ll want to differentiate between various types of dysfunctions. A thorough physical examination, including an external and internal pelvic exam, can help to rule out other causes of sexual dysfunction.