Diagnosis: Interstitial lung disease

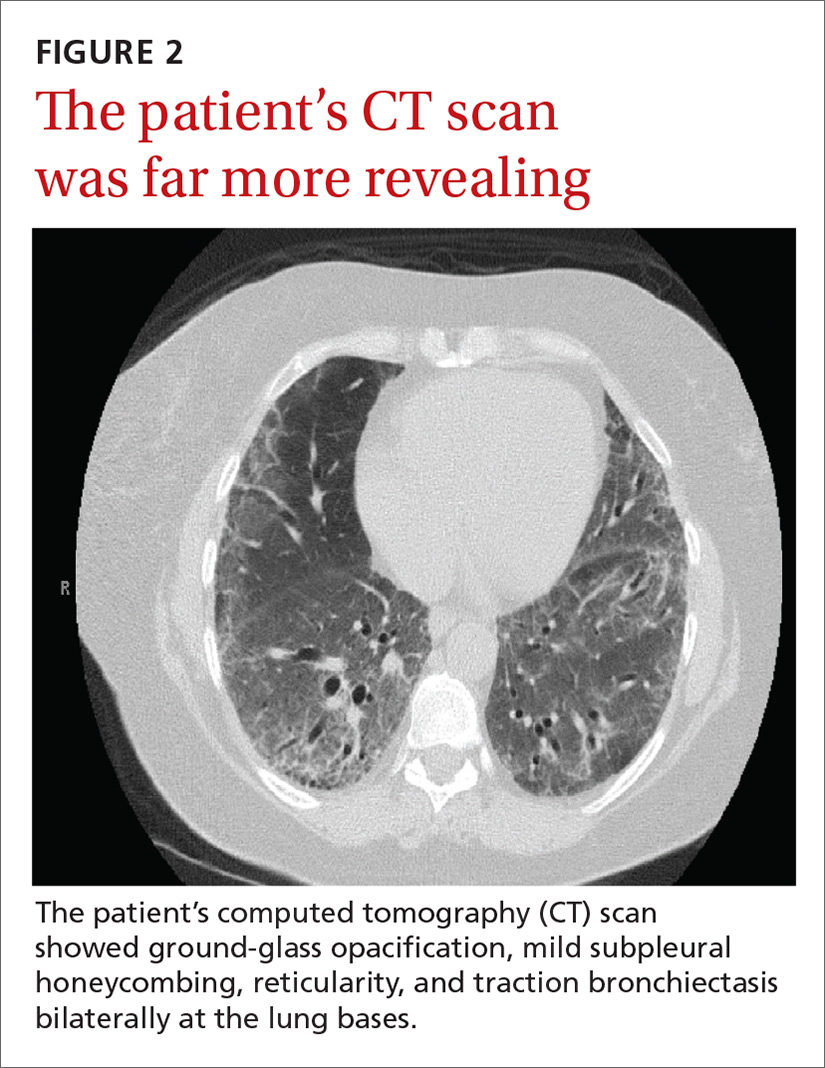

Given the patient’s worsening respiratory status, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered (FIGURE 2). Review of the CT scan showed ground-glass opacification, mild subpleural honeycombing, reticularity, and traction bronchiectasis bilaterally at the lung bases. Bronchoscopy with lavage was performed to rule out infectious etiologies and was negative. These findings, along with the patient’s medical history of RA and use of methotrexate, led us to diagnose interstitial lung disease (ILD) in this patient.

ILD refers to a group of disorders that primarily affects the pulmonary interstitium, rather than the alveolar spaces or pleura.1 The most common causes of ILD seen in primary care are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, connective tissue disease, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis secondary to drugs (such as methotrexate, citalopram, fluoxetine, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins), radiation, or occupational exposures. (Textile, metal, and plastic workers are at a heightened risk, as are painters and individuals who work with animals.)1 In 2010, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis had a prevalence of 18.2 cases per 100,000 people.2 Determining the underlying cause of ILD is important, as it may influence prognosis and treatment decisions.

The most common presenting symptoms of ILD are exertional dyspnea, cough with insidious onset, fatigue, and weakness.1,3 Bear in mind, however, that patients with ILD associated with a connective tissue disease may have more subtle manifestations of exertional dyspnea, such as a change in activity level or low resting oxygen saturations. The pulmonary exam can be normal or can reveal fine end-inspiratory crackles, and may include high-pitched, inspiratory rhonchi, or “squeaks.”1

When a diagnosis of ILD is suspected, investigation should begin with high-resolution CT (HRCT).1.3-5 In patients for whom a potential cause of ILD is not identified or who have more than one potential cause, specific patterns seen on the HRCT can help determine the most likely etiology.5 Chest x-ray has low sensitivity and specificity for ILD and can frequently be misinterpreted, as occurred with our patient.1

Rule out other causes of dyspnea

The differential diagnosis for dyspnea includes:

Heart failure. Congestive heart failure can present with acutely worsening dyspnea and cough, but is also commonly associated with orthopnea and/or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. On physical examination, findings of volume overload such as pulmonary crackles, lower extremity edema, and elevated jugular venous pressure are additional signs that heart failure is present.

Pulmonary embolism (PE). Patients with PE commonly present with acute dyspnea, chest pain, and may also have a cough. Additional risk factors for PE (prolonged immobility, fracture, recent hospitalization) may also be present. A Wells score and a D-dimer test can be used to determine the probability of a patient having PE.

Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD exacerbations commonly present with a productive cough and worsening dyspnea. Pulmonary exam findings include wheezing, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, and poor air movement.

Infection (including coccidioidomycosis in the desert southwest, where this patient lived). Our patient was initially treated for pneumonia because she had reported fevers associated with dyspnea and cough along with an elevated white blood cell count. Chest x-ray findings in patients with pneumonia can reveal either lobar consolidation or interstitial infiltrates.

Failure to respond to treatment of the more common causes of dyspnea, as occurred with our patient, should prompt consideration of ILD, particularly in those who have a history of connective tissue disease. Once a diagnosis of ILD is made, referral to a pulmonary specialist is advised.1,3