Researchers estimate that approximately 10.2 million Americans have osteoporosis, and an additional 43 million have low bone density.1 Equally stark are the ramifications of these numbers. About one out of every 2 Caucasian women will experience an osteoporosis-related fracture at some point in their lifetime, as will approximately one in 5 men.2 Although African American women tend to have a higher bone mineral density (BMD) than white women throughout their lives, those who have osteoporosis have the same elevated risk for fractures as Caucasians.

Osteoporotic fractures are associated with increased risk of disability, mortality, and nursing home placement. Given the aging population, researchers expect annual direct costs from osteoporosis to reach $25.3 billion by 2025.3

Family physicians (FPs) can have a meaningful impact on the extent to which this condition affects the population. To that end, we’ve put together a brief summary of the screening recommendations to keep in mind and a comparison of the different agents used to treat and prevent osteoporosis. The reference tables throughout will put these details at your fingertips.

Screening recommendations vary, Dx doesn’t require BMD testing

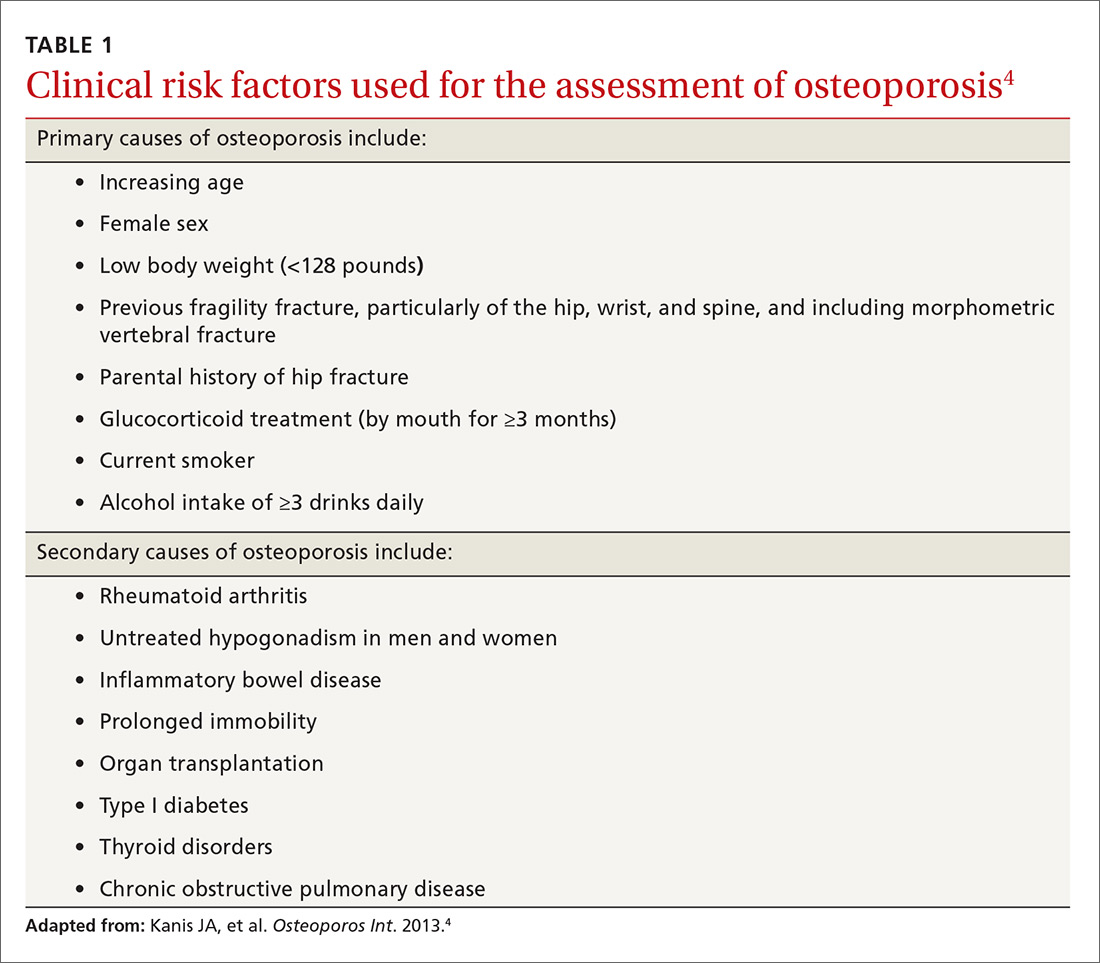

Guidelines for screening for osteoporosis vary considerably by professional organization. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening all women ≥65 years, and younger women whose fracture risk is the same, or greater than, that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors (TABLE 14).5 In addition, the USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for osteoporosis in men.5

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends that BMD testing be performed in all women ≥65 years and in men ≥70 years.6 In terms of frequency, NOF recommends BMD testing one to 2 years after initiating therapy to reduce fracture risk and every 2 years thereafter. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends BMD screening for women no more than every 2 years starting at age 65 years.7 It also recommends selective screening in women younger than 65 years of age if they are postmenopausal and have other risk factors for osteoporosis.7

The most recent guideline regarding osteoporosis was published in May 2017 by the American College of Physicians (ACP) and endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians.8 But the guideline focuses on treatment rather than screening.

Although guidelines vary by society, most experts agree with BMD assessment in all women ≥65 years and postmenopausal women <65 years if one or more of the risk factors identified in TABLE 14 are present.

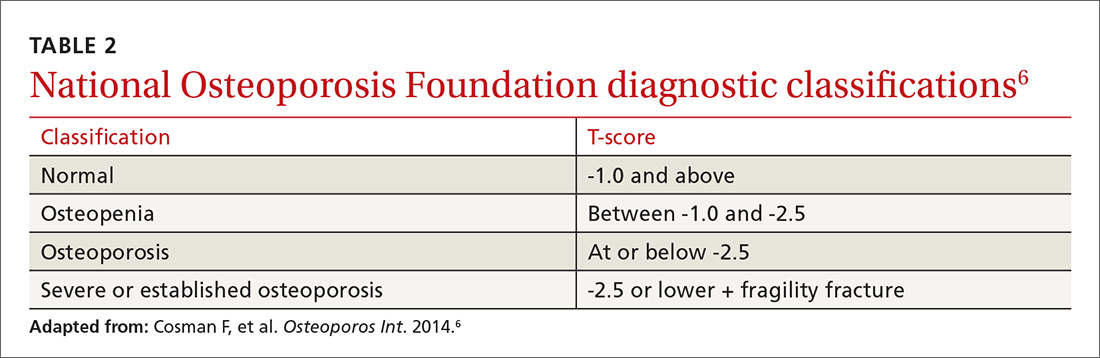

Diagnosis. Osteoporosis can be diagnosed using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and T-score (TABLE 26),9 but BMD testing is not always necessary to establish the diagnosis. For example, osteoporosis can be diagnosed clinically in both men and women who have sustained a hip fracture (with or without BMD testing). Osteoporosis may also be diagnosed in patients with osteopenia (determined by DXA and T-score) who have had a vertebral, proximal humeral, or pelvic fracture. Generally speaking, a detailed history and physical together with BMD assessment, vertebral imaging to diagnose vertebral fractures, and, when appropriate, the World Health Organization’s 10-year estimated fracture probability, are all utilized to establish patients’ fracture risk.6,10

Treatment: Which agents and for how long?

Once a patient is diagnosed with osteoporosis, answering the following questions will help with selection of the best therapy for the patient:

- Where on the body is BMD the lowest (vertebral, nonvertebral, or hip) and, consequently, at highest risk for a fracture?

- Does the patient have any conditions that would interfere with therapy (difficulty swallowing, esophageal/gastrointestinal irritation)? This is important, as certain agents are associated with severe esophagitis.

- Does the patient have any issues that would prevent adherence? Adherence may improve with therapy that is administered less frequently (weekly, monthly, once every 3 months, or annually).

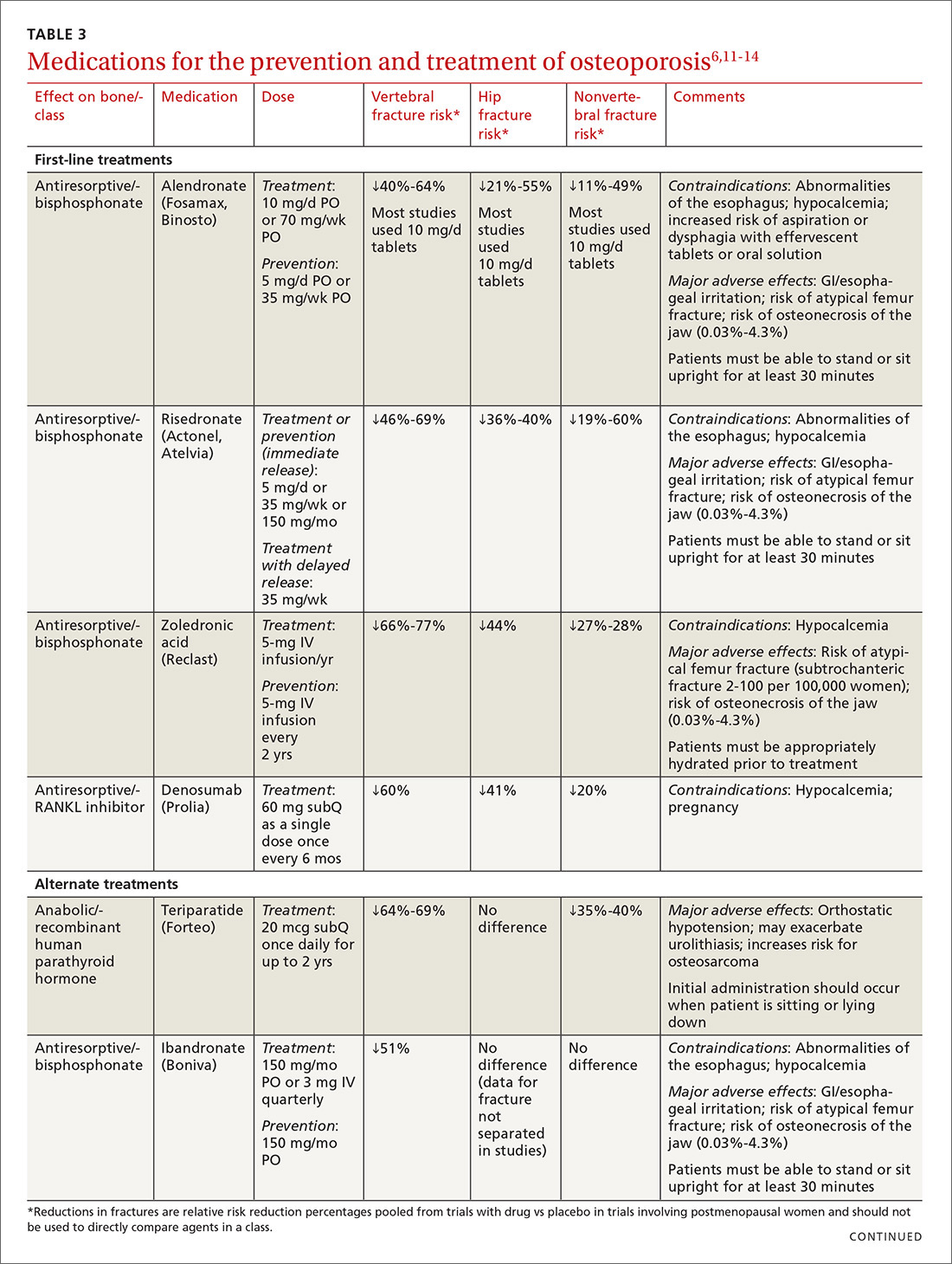

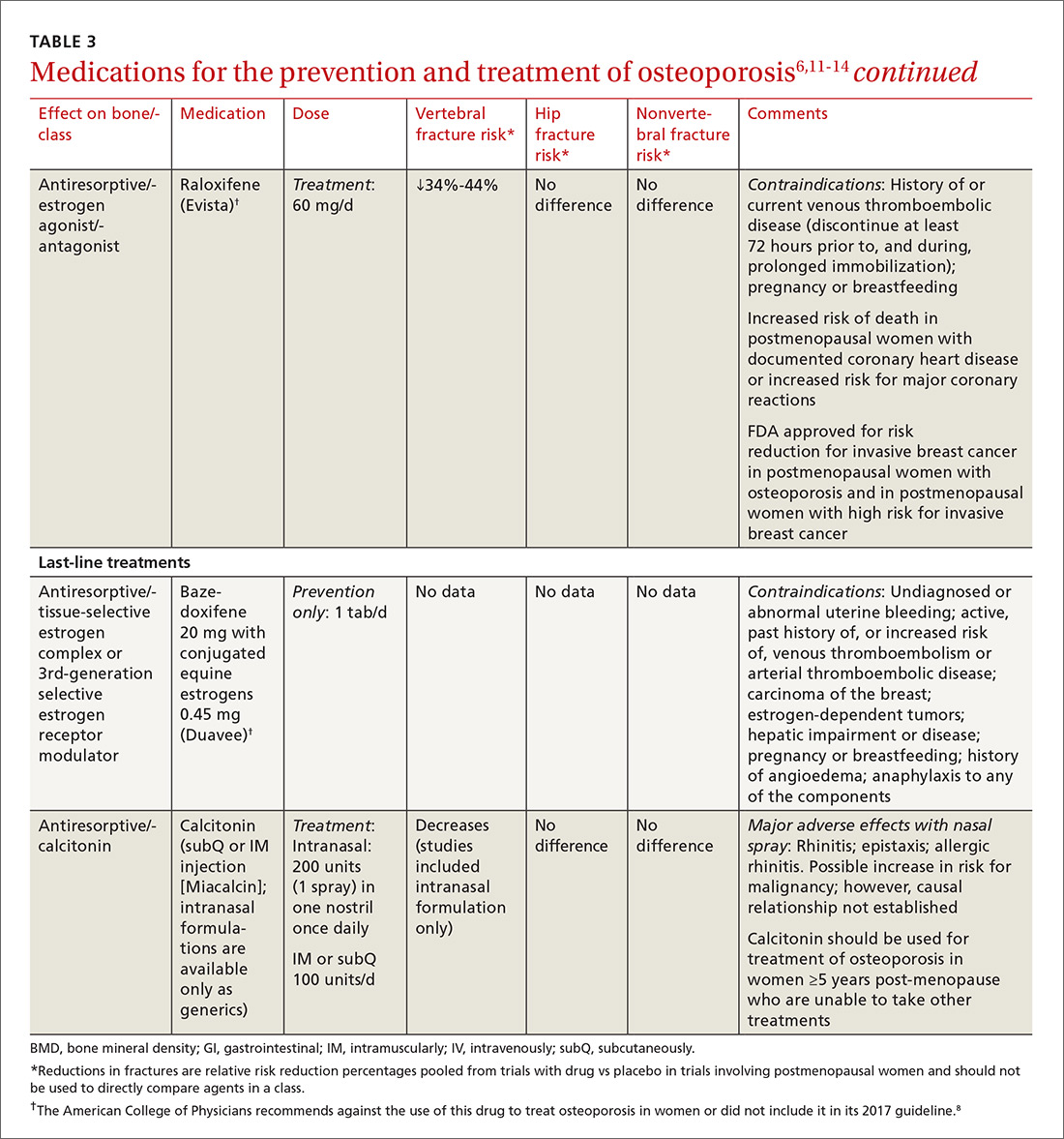

TABLE 36,11-14 lists the prescription medications used to treat and prevent osteoporosis, their effect on the risk of vertebral, hip, and nonvertebral fractures, and contraindications/major adverse effects. First-line therapies are recommended based on clinical trials comparing the medication to placebo and evaluating their effectiveness in lowering the risk of vertebral, hip, and nonvertebral fractures.15 Given the absence of studies comparing these drugs to one another, TABLE 36,11-14 should not be used to make direct comparisons.

A new monoclonal antibody, romosozumab, has shown statistically significant decreases in the risk of new vertebral and nonvertebral fractures compared to alendronate after 12 months of use.16 However, there was a statistically significant higher number of patients who had a cardiac ischemic event or revascularization while taking romosozumab compared with those taking alendronate in the one-year double-blind period of the study.16 As of press time, the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved romosozumab.