Addressing caregiver stress, anxiety disorders afterward

Regardless of the setting in which FPs work, witnessing or being directly involved in a traumatic event puts one at risk for symptoms—or a full diagnosis—of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, or anxiety or mood disorders.24,25 Although findings vary, studies have found that as many as 12% of ED personnel meet the criteria for PTSD26,27 and 12% to 15% report having been threatened physically.28,29 More than half of physicians in another study had witnessed a physical attack.30

Physicians and other health care personnel who have experienced a traumatic incident, or offered help to another during an incident, may attempt to cope through avoidance, cutting down on work hours, leaving the work setting in which the event took place, or leaving the profession altogether.29,31,32

There is a paucity of methodologically sound research with regard to prevention and treatment of PTSD symptoms in this population.24 According to a 2002 Cochrane review, the effectiveness of individual, single-session debriefing does not have solid research support,33 and there are concerns about potential harms due to reliving the traumatic event when sessions are led by poorly trained debriefing staff.34-36

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), however, holds promise in terms of facilitating a return to pretrauma functioning based on studies of first responders.34,35 This may be because CISD follows a specific protocol and that group sessions may capitalize on the social support/camaraderie within a group that has undergone a traumatic event.34,35 It is important that those providing debriefing and support be well-trained.35

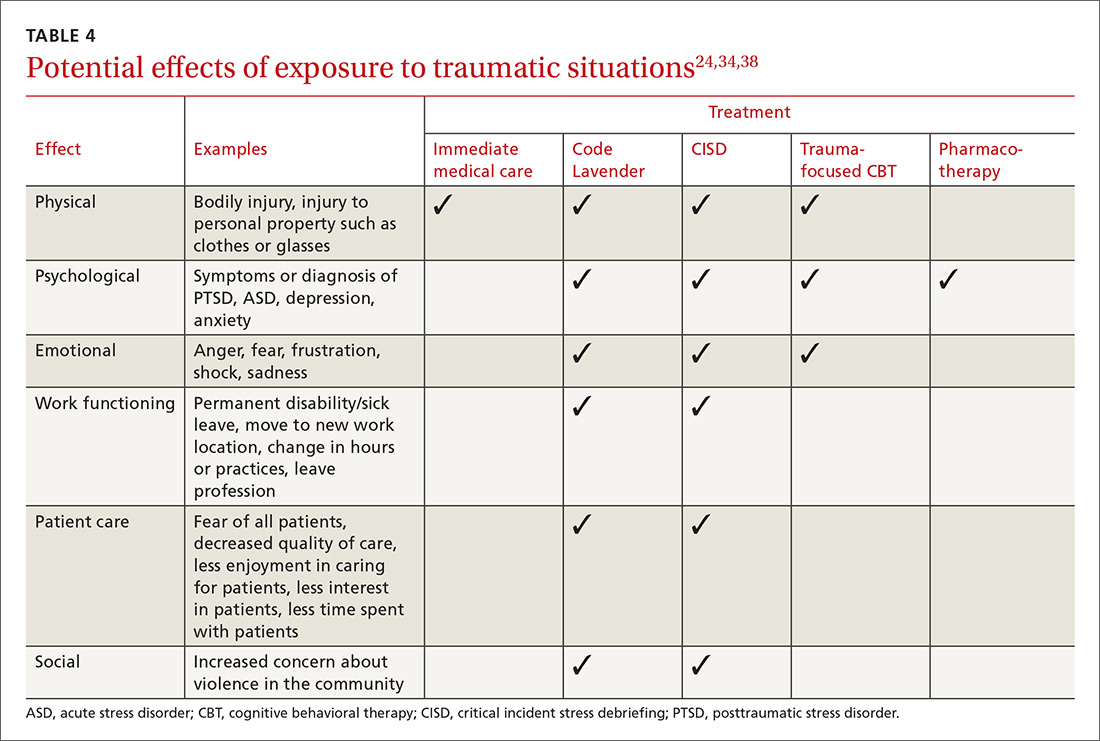

Debriefing, however, is not always sufficient, and those who appear to be affected on an ongoing basis may require individual treatment for PTSD symptoms. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as trauma-focused psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, may be considered37 (TABLE 424,34,38).

Ongoing support in the workplace. The Cleveland Clinic has developed a “Code Lavender” to combat stress in the workplace. Like a Code Blue for medical emergencies, a Code Lavender is called when a health care worker is in need of emotional or spiritual support.38 A provider who initiates the call is met by a team of holistic nurses within 30 minutes. The team provides Reiki and massage, healthy snacks and water, and lavender arm bands to remind the individual to relax for the rest of the day. Further opportunities for spiritual support, mindfulness training, counseling, and yoga may also be made available.

CASE Sensing that the situation with my patient might escalate, I lowered my voice, relaxed my shoulders, leaned casually against the desk, and asked him to tell me how I could best help him. As he spoke, I offered him a seat (by gesturing to the chair). I did this for 2 reasons: to move him away from blocking my exit from the room, and to put him at a lower level than me so that he was entirely in my view. I didn’t interrupt him as he spoke. I just nodded or tilted my head to show I was listening. In my mind, I played out the various scenarios that could ensue.

Fortunately, I was able to get him to relax enough for an assessment, which involved a more relevant history and the exam, which he agreed to once an aide had come into the room. He did not exhibit the concerning signs of flushed skin, dilated pupils, shallow rapid respirations, or perspiration. He did have a comorbid behavioral health issue, which we were able to address. His earlier behavioral indicators of agitation were controlled with verbal and physical cues on my part. Our conversation didn't reveal an intent to harm himself or others. In this case, physical restraints were not required. Throughout the encounter the door was left open, and the patient was reminded that we were there to help.

Once he left, I made the relevant notes in the chart regarding his agitated state at the start of the visit and his final state at the end of the visit so as to assist any other providers. We (TIM, MG) also held a quick debrief after the encounter with the office staff and decided that we needed to create a policy and protocol regarding how to handle such situations in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, Family Medicine Department, Southside Hospital, 301 East Main Street, Bay Shore, NY 11706; tmalize@northwell.edu.