The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis no longer needs to include a trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to an updated international consensus statement published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

“An initial rationale for the PPI trial was to distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease, but it is now known that these conditions have a complex relationship and are not necessarily mutually exclusive,” wrote Evan S. Dellon, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his associates. According to current evidence, “PPIs are better classified as a treatment for esophageal eosinophilia that may be due to eosinophilic esophagitis than as a diagnostic criterion,” they said.

Diagnostic guidelines for eosinophilic esophagitis were published first in 2007 and were updated in 2011. The guideline authors recommended either pH monitoring or an 8-week trial of high-dose PPI therapy to rule out inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

But subsequent publications described patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia who responded to PPIs and lacked classic GERD symptoms. Guidelines called this condition “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” and considered it a separate entity from GERD.

However, an “evolving body of research” shows that eosinophilic esophagitis can overlap with GERD, Dr. Dellon and his associates wrote. Furthermore, each of these conditions can trigger the other. Eosinophilic esophagitis can decrease esophageal compliance, leading to secondary reflux, while gastroesophageal reflux can erode the esophageal epithelium, triggering antigen exposure and eosinophilia.

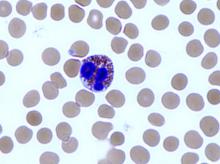

Therefore, Dr. Dellon and his associates recommended defining eosinophilic esophagitis as signs and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and an esophageal biopsy showing at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field, or approximately 60 eosinophils per millimeter, with infiltration limited to the esophagus. They stressed the importance of esophageal biopsy even if endoscopy shows normal mucosa. “As per prior guidelines, multiple biopsies from two or more esophageal levels, targeting areas of apparent inflammation, are recommended to increase the diagnostic yield,” they added. “Gastric and duodenal biopsies should be obtained as clinically indicated by symptoms, endoscopic findings in the stomach or duodenum, or high index of suspicion for a mucosal process.”

Physicians should increase their suspicion of eosinophilic esophagitis if patients have other types of atopy or endoscopic findings of “rings, furrows, exudates, edema, stricture, narrowing, and crepe-paper mucosa,” they added. In addition to GERD, they recommended looking carefully for other conditions that can trigger esophageal eosinophilia, such as pemphigus, drug hypersensitivity reactions, achalasia, and Crohn’s disease with esophageal involvement.

To create the guideline, Dr. Dellon and his associates searched PubMed for studies of all designs and sizes published from 1966 through December 2016. Teams of experts on specific topics then reviewed and discussed relevant literature. In May 2017, 43 reviewers met for 8 hours to present and discuss conclusions. There was 100% agreement to remove the PPI trial from the diagnostic criteria, the experts noted.

The authors disclosed financial support from the International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Diseases Researchers (TIGERS), The David and Denise Bunning Family, and the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. Dr. Dellon disclosed consulting relationships and receiving research funding from Adare, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire among others. The majority of his coauthors also disclosed relationships with numerous medical companies.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul 12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.