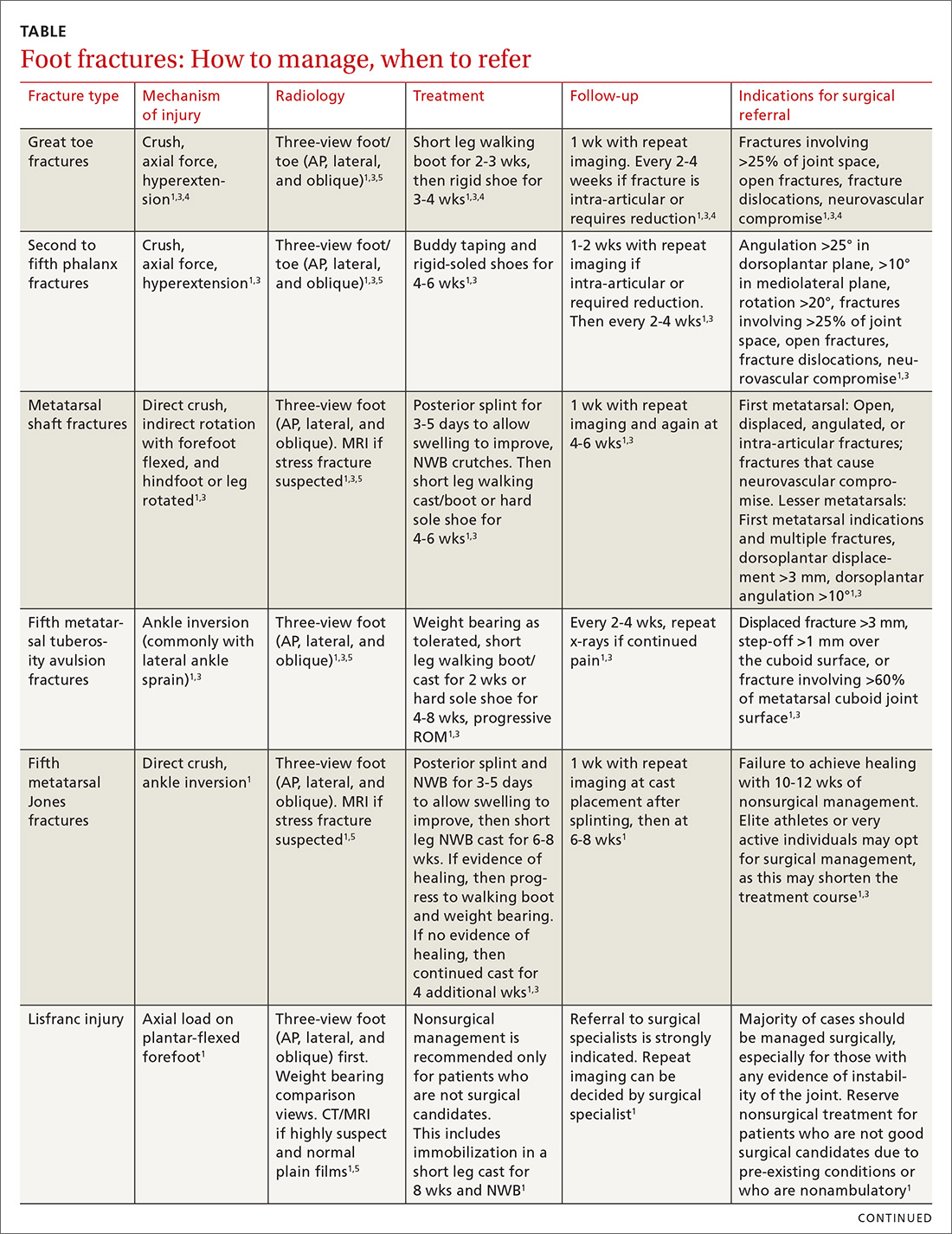

The evaluation and management of acute musculoskeletal conditions are frequently handled by primary care providers.1 It’s estimated that up to 14% of orthopedic complaints encountered by family physicians involve fractures,2 and approximately 15% of these are foot fractures.2 Diagnosis requires radiographic evaluation, but ultrasound is proving useful, too. This article reviews the diagnosis and management of adult foot fractures, with an emphasis on when advanced imaging and referral are indicated (TABLE1,3-10).

Phalanx fractures: The most common foot fractures

Phalanx fractures typically occur by crush injury, hyperextension, or direct axial force (eg, stubbing the toe).3 Patients with phalanx fractures typically present with pain at or near the site of injury, edema, ecchymosis, and erythema. Throbbing pain is characteristic, and dependent position may worsen the pain.1 Emergently evaluate any fracture causing tenting of the skin, protrusion from the skin, or neurovascular compromise, and attempt realignment to regain neurovascular function.

Most patients with phalanx fractures have point tenderness over the site of the fracture; however, this may also occur with contusions. Placing a gentle loading force along the long axis of the bone distal to the injury may help you differentiate between a contusion and a fracture.4 Pain observed with axial loading of the bone during examination points to a fracture rather than a contusion.

Differential diagnosis

Obtain imaging, including anterior-posterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views at a minimum, for all patients in whom you suspect fractures.5 Multiple fractures of the phalanges are common; therefore, always thoroughly examine the phalanges adjacent to the injured one.

Sesamoid bone fractures are uncommon but do occur and are usually due to direct injury from jumping or landing. The most common sesamoid to be injured is the medial sesamoid of the great toe, although the lateral sesamoid can also be injured. Bipartite sesamoids can occur and may confuse the examiner due to their similar appearance on x-rays to a sesamoid fracture.1 These normal variants often appear smooth and are commonly bilateral as opposed to the jagged or abrupt edges of a fracture. Stress fractures occur as well and are typically due to overuse-type injuries.

Other causes of pain similar to that experienced with phalanx fractures include soft tissue injuries to adjacent ligaments, tendons, and muscles. To help discern the cause of pain, evaluate nail beds for subungual hematomas, indicating injury to the nail bed causing bleeding and pressure under the nail. Obvious deformities of the toes or metatarsal-phalangeal joints signal the possibility of a fracture-dislocation. First metatarsophalangeal (MTP) sprain (“turf toe,” a condition common in athletes who hyperextend the toe, such as when pushing off from hard surfaces like turf) and gout can also present with acute pain in the first phalanx.

Treatment

Due to the role of the great toe in weight bearing and balance, great toe fractures are sometimes managed differently than fractures in Toes 2 through 5. Proper alignment and healing from a fracture in the first toe are critical to prevent future pain and other sequelae. Refer for orthopedic evaluation great toe fractures with displacement, angulation, rotational deformity, neurovascular compromise, >25% involvement of the joint space, or obvious dislocation.1 If referral is not indicated, treat great toe fractures with a short leg walking cast/boot for 2 to 3 weeks followed by buddy taping and use of a hard-soled shoe for 3 to 4 weeks.1

Continue to: With regard to the lesser toes...