THE CASE

A 4-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with genital discomfort and dysuria of 6 months’ duration. The patient’s mother said that 3 days earlier, she noticed a tear near the child’s clitoris and a scab on the labia minora that the mother attributed to minor trauma from scratching. The pediatrician was concerned about genital trauma from sexual abuse and referred the patient to the emergency department, where a report with child protective services (CPS) was filed. The mother reported that the patient and her 8-year-old sibling spent 3 to 4 hours a day with a babysitter, who was always supervised, and the parents had no concerns about possible sexual abuse.

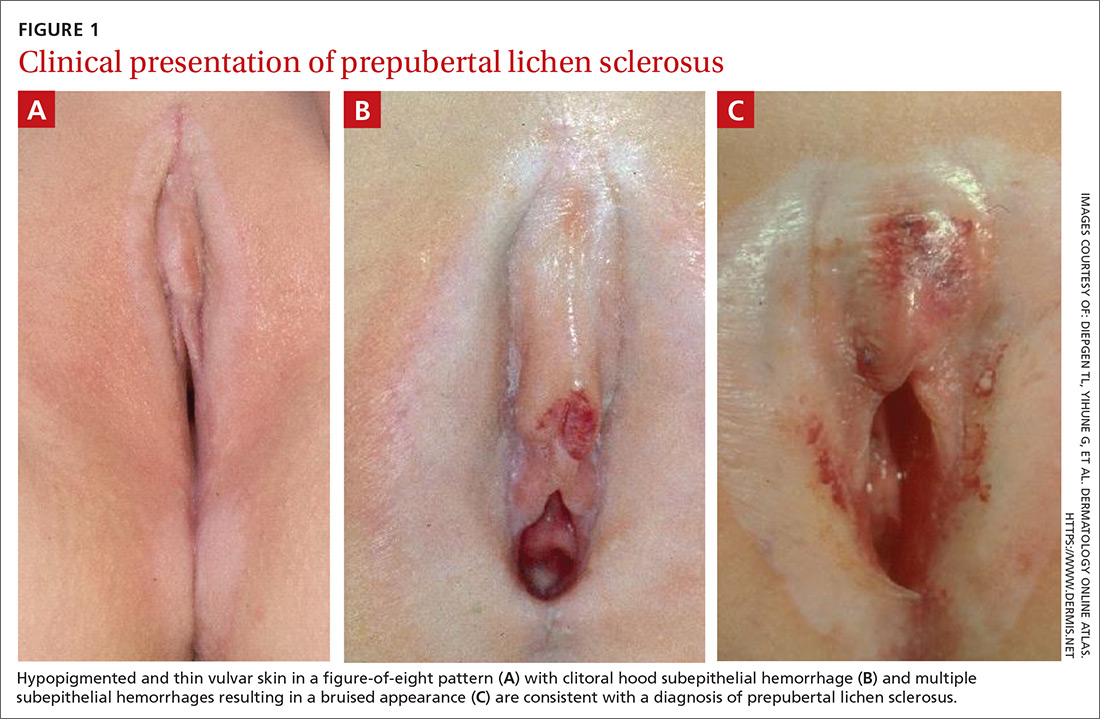

Physical examination by our institution’s Child Protection Team revealed clitoral hood swelling with subepithelial hemorrhages, a blood blister on the right labia minora, a fissure and subepithelial hemorrhages on the posterior fourchette, and a thin depigmented figure-of-eight lesion around the vulva and anus.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Since the clinical findings were consistent with prepubertal lichen sclerosus (LS), the CPS case was closed and the patient was referred to Pediatric Gynecology. Treatment with high-potency topical steroids was initiated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 2 weeks, then once daily for 2 weeks. She was then switched to triamcinolone ointment 0.01% twice daily for 2 weeks, then once daily for 2 weeks. These treatments were enough to stop the LS flare and decrease the anogenital itching.

DISCUSSION

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that primarily presents in the anogenital region; however, extragenital lesions on the upper extremities, thighs, and breasts have been reported in 15% to 20% of patients.1 Lichen sclerosus most commonly affects females as a result of low estrogen and may occur during puberty or following menopause, but it also is seen in males.1,2 The estimated prevalence of LS in prepubertal girls is 1 in 900.3 The effects of increased estrogen exposure on LS during puberty are not entirely clear. Lichen sclerosus previously was thought to improve with puberty, since it is not as common in women of reproductive age; however, studies have shown persistent symptoms after menarche in some patients.4-6

The pathogenesis of LS is multifactorial, likely with an autoimmune component, as it often is associated with other autoimmune findings such as thyroiditis, alopecia, pernicious anemia, and vitiligo.2 Diagnosis of prepubertal LS usually is made based on a review of the patient’s history and clinical examination. Presenting symptoms may include pruritus, skin irritation, vulvar pain, dysuria, bleeding from excoriations, fissures, and constipation.1,3,7

On physical examination, LS can present on the anogenital skin as smooth white spots or wrinkled, blotchy, atrophic patches. The skin around the vaginal opening and anus is thin and often is described as resembling parchment or cigarette paper in a figure-of-eight pattern (FIGURE 1A). Vulvar and anal fissures and subepithelial hemorrhages with the appearance of blood blisters also can be found (FIGURE 1B).8 Affected areas are fragile and susceptible to minor trauma, which may result in bruising or bleeding (FIGURE 1C).

Over time, scarring can occur and may result in disruption of the anogenital architecture—specifically loss of the labia minora, narrowing of the introitus, and burying of the clitoris.1,2 These changes can be similar to the scarring seen in postmenopausal women with LS.

Continue to: The differential diagnosis...