Several screening tools are available for exploring a patient’s suicidality. Unfortunately, most of them are supported by limited evidence of effectiveness in identifying suicide risk.8-10 An exception is the well-researched and commonly used Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).18,19 In a comparative study conducted at 2 primary care clinics, researchers found that the suicide item included in the PHQ-9 provided poor sensitivity but moderate specificity (60% and 84%, respectively),20 while the C-SSRS showed high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96%-100%) in accurately identifying various suicidal self-injurious behaviors above and beyond what was identified through a structured clinical interview.20 Free copies of the C-SSRS, training materials, and follow-up assessments in multiple languages can be obtained on The Columbia Lighthouse Project Web site (http://cssrs.columbia.edu/).19

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

While there is debate regarding whom to screen for suicide, the importance of intervention when a patient is revealed to be at risk is clear. After completing a comprehensive suicide risk assessment, designate the patient’s level of risk as high, moderate, or low, and follow a stepped approach to clinical care (see the Assessment and Interventions with Potentially Suicidal Patients table (page 31) at https://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/Final%20National%20Suicide%20Prevention%20Toolkit%202.15.18%20FINAL.pdf).11 Provide any patient at risk, regardless of level, with contact information for local crisis and peer support as well as national resources (National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, (800) 273-TALK (8255), https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/; Crisis Text Line, Text HOME to 741741, https://www.crisistextline.org/).

When a patient is at high risk for suicide and reports an imminent plan or intent, ensure their safety through inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and then close follow-up upon hospital discharge. First encourage voluntary hospitalization in a collaborative discussion with the patient; resort to involuntary hospitalization only if the patient resists.

What not to do. When the patient does not require immediate hospitalization, evidence recommends against contracting for patient safety via a written contract or requiring patients to verbally guarantee that they will not commit suicide upon leaving a provider’s office.21 Concerns about such contracts include a lack of evidence supporting their use, decreased vigilance by health care workers when such contracts are in place, and questions regarding informed consent and competence.21 Instead, engage a patient who is at moderate or low risk in safety planning, and meet with the patient frequently to discuss continued safety planning through close follow-up (or with a behavioral health provider if available).10-12,22 With patients previously identified as at high risk for suicide who return from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, continue to screen them for suicide at subsequent visits and engage them in collaborative safety planning.

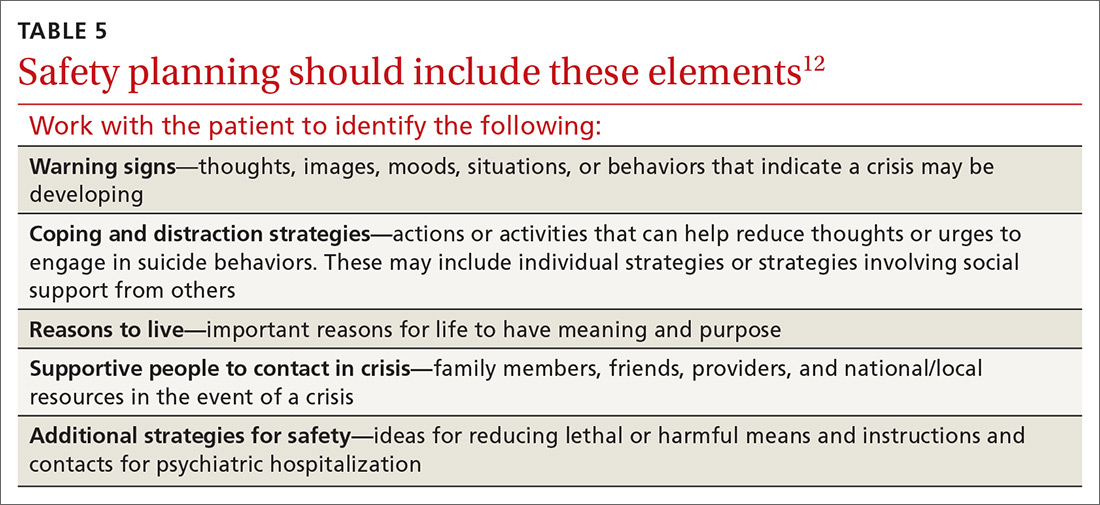

Safety planning (TABLE 512), also known as crisis response planning, is considered a best practice and effective suicide prevention intervention by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention.23 Safety planning involves a collaboration between patient and physician to identify risk factors and protective factors along with crisis resources and strategies to reduce engagement in suicide behaviors.12,22

Continue to: THE CASE