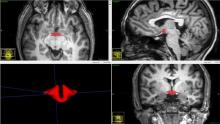

CHICAGO – Women taking oral contraceptives had, on average, a hypothalamus that was 6% smaller than those who didn’t, in a small study that used magnetic resonance imaging. Pituitary volume was also smaller.

Though the sample size was relatively small, 50 women in total, it’s the only study to date that looks at the relationship between hypothalamic volume and oral contraceptive (OC) use, and the largest examining pituitary volume, according to Ke Xun (Kevin) Chen, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Using MRI, Dr. Chen and his colleagues found that hypothalamic volume was significantly smaller in women taking oral contraceptives than those who were naturally cycling (b value = –64.1; P = .006). The pituitary gland also was significantly smaller in those taking OCs (b = –92.8; P = .007).

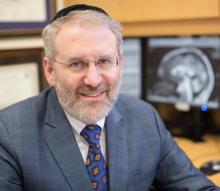

“I was quite surprised [at the finding], because the magnitude of the effect is not small,” especially in the context of changes in volume of other brain structures, senior author Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, said in an interview. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a volume loss of 4% annually can be expected.

However, “it’s not shocking to me in a negative way at all. I can’t tell you what it means in terms of how it’s going to affect people,” since this is a cross-sectional study that only detected a correlation and can’t say anything about a causative relationship, he added. “We don’t even know that [OCs] cause this effect. ... It’s plausible that this is just a plasticity-related change that’s simply showing us the effect of the drug.

“We’re going to be much more careful to consider oral contraceptive use as a covariate in future research studies; that’s for sure,” he said.

Although OCs have been available since their 1960 Food and Drug Administration approval, and their effects in some areas of physiology and health have been well studied, there’s still not much known about how oral contraceptives affect brain function, said Dr. Lipton, professor of neuroradiology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Montefiore medical system, New York.

The spark for this study came from one of Dr. Lipton’s main areas of research – sex differences in susceptibility to and recovery from traumatic brain injury. “Women are more likely to exhibit changes in their brain [after injury] – and changes in their brain function – than men,” he said.

In the present study, “we went at this trying to understand the effect to which the hormone effect might be doing something in regular, healthy people that we need to consider as part of the bigger picture,” he said.

Dr. Lipton, Dr. Chen (then a radiology resident at Albert Einstein College of Medicine), and their coauthors constructed the study to look for differences in brain structure between women who were experiencing natural menstrual cycles and those who were taking exogenous hormones, to begin to learn how oral contraceptive use might modify risk and susceptibility for neurologic disease and injury.

It had already been established that global brain volume didn’t differ between naturally cycling women and those using OCs. However, some studies had shown differences in volume of some specific brain regions, and one study had shown smaller pituitary volume in OC users, according to the presentation by Dr. Chen, who is now a radiology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Accurately measuring hypothalamic volume represents a technical challenge, and the effect of OCs on the structure’s volume hadn’t previously been studied.

Sex hormones, said Dr. Lipton, have known trophic effects on brain tissue and ovarian sex hormones cross the blood brain barrier, so the idea that there would be some plasticity in the brains of those taking OCs wasn’t completely surprising, especially since there are hormone receptors that lie within the central nervous system. However, he said he was “very surprised” by the effect size seen in the study.

The study included 21 healthy women taking combined oral contraceptives, and 29 naturally cycling women. Participants’ mean age was 23 years for the OC users, and 21 for the naturally cycling women. Body mass index and smoking history didn’t differ between groups. Women on OCs were significantly more likely to use alcohol and to drink more frequently than those not taking OCs (P = .001). Participants were included only if they were taking a combined estrogen-progestin pill; those on noncyclical contraceptives such as implants and hormone-emitting intrauterine devices were excluded, as were naturally cycling women with very long or irregular menstrual cycles.

After multivariable statistical analysis, the only two significant predictors of hypothalamic volume were total intracranial volume and OC use. For pituitary volume, body mass index and OC use remained significant.

In addition to the MRI scans, participants also completed neurobehavioral testing to assess mood and cognition. An exploratory analysis showed no correlation between hypothalamic volume and the cognitive testing battery results, which included assessments for verbal learning and memory, executive function, and working memory.

However, a moderate positive association was seen between hypothalamic volume and anger scores (r = 0.34; P = .02). The investigators found a “strong positive correlation of hypothalamic volume with depression,” said Dr. Chen (r = 0.25; P = .09).

The investigators found no menstrual cycle-related changes in hypothalamic and pituitary volume among naturally cycling women.

Hypothalamic volume was obtained using manual segmentation of the MRIs; a combined automated-manual approach was used to obtain pituitary volume. Reliability was tested by having 5 raters each assess volumes for a randomly selected subset of the scans; inter-rater reliability fell between 0.78 and 0.86, values considered to indicate “good” reliability.

In addition to the small sample size, Dr. Chen acknowledged several limitations to the study. These included the lack of accounting for details of OC use including duration, exact type of OC, and whether women were taking the placebo phase of their pill packs at the time of scanning. Additionally, women who were naturally cycling were not asked about prior history of OC use.

Also, women’s menstrual phase was estimated from the self-reported date of the last menstrual period, rather than obtained by direct measurement via serum hormone levels.

Dr. Lipton’s perspective adds a strong note of caution to avoid overinterpretation from the study. Dr. Chen and Dr. Lipton agreed, however, that OC use should be accounted for when brain structure and function are studied in female participants.

Dr. Chen, Dr. Lipton, and their coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The authors reported no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Chen K et al. RSNA 2019. Presentation SSM-1904.