THE CASE

A 78-year-old man with a history of diabetes and hypertension was referred to the outpatient surgical office with a chief complaint of “tail bone pain” that had started after a fall a year earlier. The patient complained that the pain was worse when sitting and at nighttime. He also admitted to a 7-lb weight loss over the past 2 months without change in diet or appetite. He denied symptoms of incontinence, urinary retention, sharp stabbing pains in the lower extremities, night sweats, or anorexia.

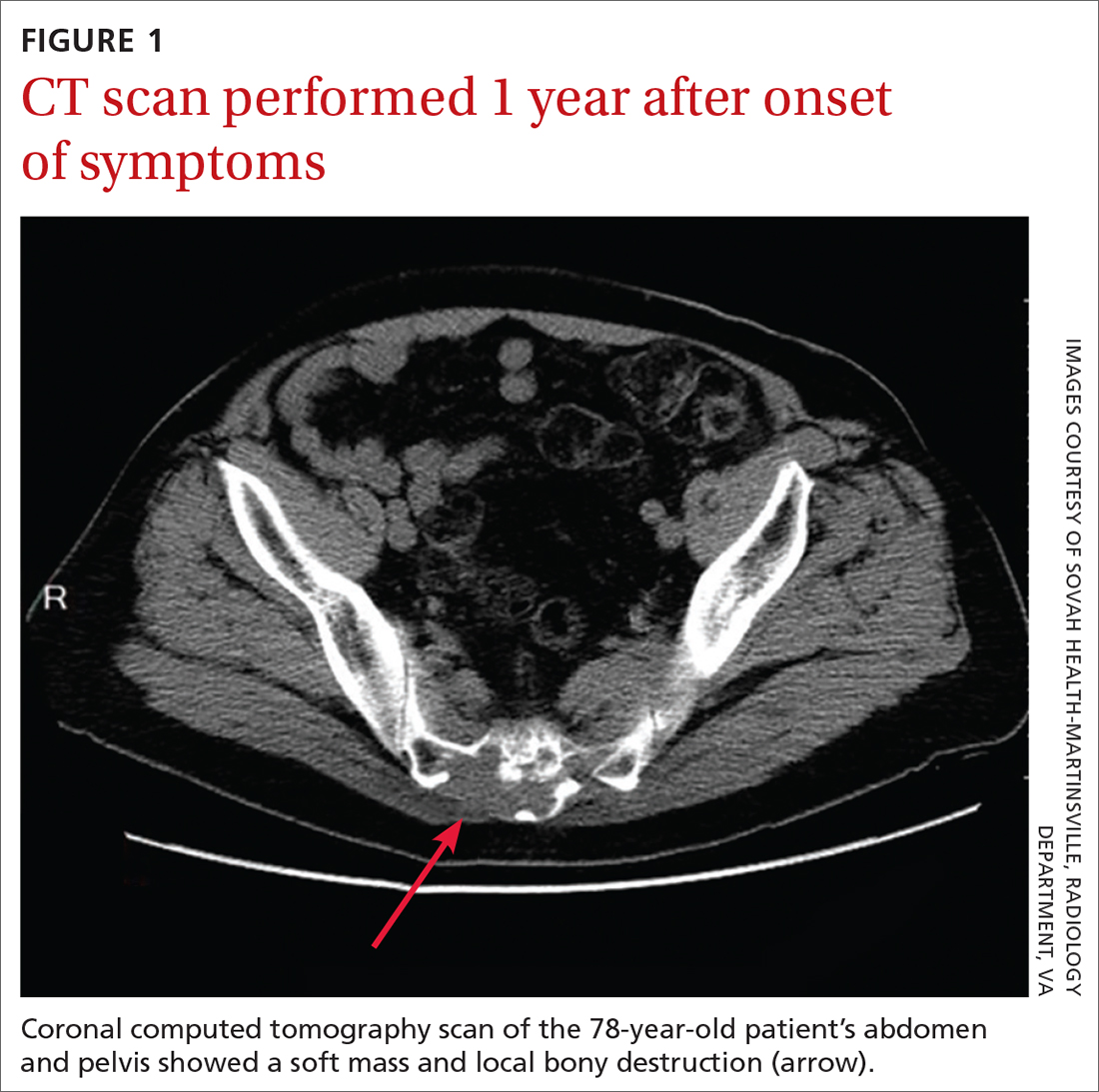

The patient first visited an urgent care facility on the day after the fall because he was experiencing pain in his “tail bone” region while riding his lawn mower. A pelvic x-ray was performed at that time and showed no coccyx fracture. He received a steroid injection in the right sacroiliac joint, which provided some relief for a month. Throughout the course of the year, he was given 6 steroid injections into his sacroiliac joint by his primary care provider (PCP) and clinicians at his local urgent care facility. One year after the fall, the patient’s PCP ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis, which revealed a 4.6 x 7.5–cm soft-tissue mass with bony destruction of the lower sacrum and coccyx that extended into the sacral and coccygeal canal (FIGURE 1).

On exam in our surgical office, the patient was found to be alert and oriented. His neurologic exam was unremarkable, with an intact motor and sensory exam and no symptoms of cauda equina syndrome. During palpation over the lower sacrum and coccyx, both tenderness and a boggy, soft mass were observed. Nerve impingement was most likely caused by the size of the mass.

THE DIAGNOSIS

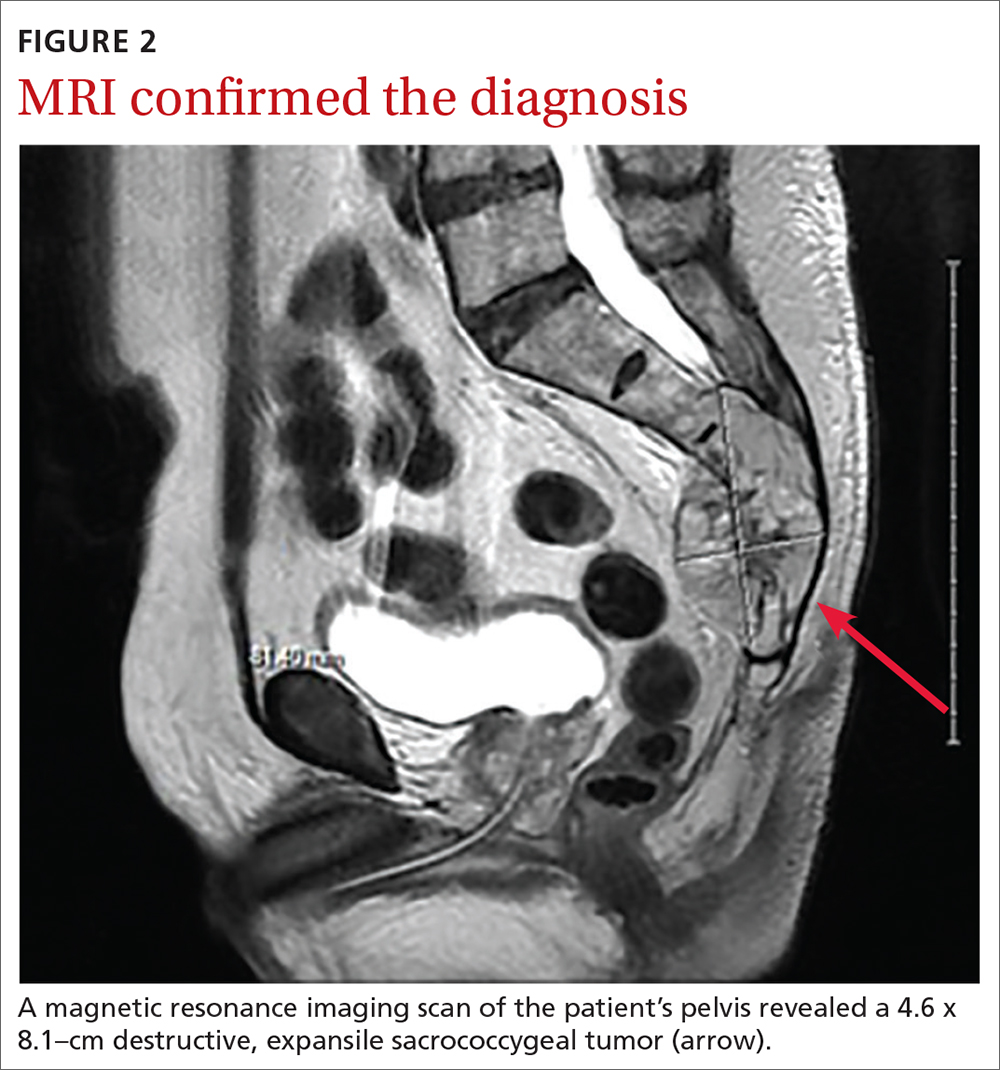

Biopsy revealed a large tan-gray, gelatinous, soft-tissue mass that was necrotizing through the lower sacrum. The diagnosis of a sacral chordoma was confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis, which demonstrated a 4.6 × 8.1–cm destructive expansile sacrococcygeal tumor with an exophytic soft-tissue component (FIGURE 2). The tumor also involved the piriformis and gluteus maximus muscles bilaterally.

DISCUSSION

Chordomas are rare, malignant bone tumors that grow slowly and originate from embryonic remnants of the notochord.1 They are most commonly seen in the sacrococcygeal segment (50%) but are also seen in the spheno-occipital synchondrosis (30%-35%) and other spinal segments such as C2 and lumbar spine.2 Chordomas are typically seen in middle-aged patients, with sacral chordomas occurring predominantly in men compared to women (3:1).2

Slow to grow, slow to diagnose

The difficulty with diagnosing sacral chordomas lies in the tendency for these tumors to grow extremely slowly, making detection challenging due to a lack of symptoms in the early clinical course. Once the tumors cause noticeable symptoms, they are usually large and extensively locally invasive. As a result, most patients experience delayed diagnosis, with an average symptom duration of 2.3 years prior to diagnosis.3

Reexamining a common problem as a symptom of a rare condition

The most commonly manifesting symptom of sacral chordomas is lower back pain that is typically dull and worse with sitting.3,4 Since lower back pain is the leading cause of disability, it is difficult to determine when back pain is simply a benign consequence of aging or muscular pain and when it is, in fact, pathologic.5 A thorough history and physical are crucial in making the distinction.

Continue to: Clinical red flags...