THE CASE

A 52-year-old man with a history of hypertension and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope. He reported that the syncope occurred soon after he stood up to go to the kitchen to make dinner but was without prodrome or associated symptoms. He recalled little of the event, and the episode was unwitnessed. He had a few bruises on his arms but no significant injuries.

On questioning, he reported occasional palpitations but no changes in his normal exercise tolerance. His only medication was lisinopril 10 mg/d.

In the ED, his vital signs, physical exam (including orthostatic vital signs), basic labs (including troponin I), and a 12-lead EKG were normal. After a cardiology consultation, he was discharged home with a 30-day ambulatory rhythm monitor.

A few days later, while walking up and down some hills, he experienced about 15 seconds of chest pain accompanied by mild lightheadedness. Thinking it might be related to his GERD, he took some over-the-counter antacids when he returned home, since these had been effective for him in the past.

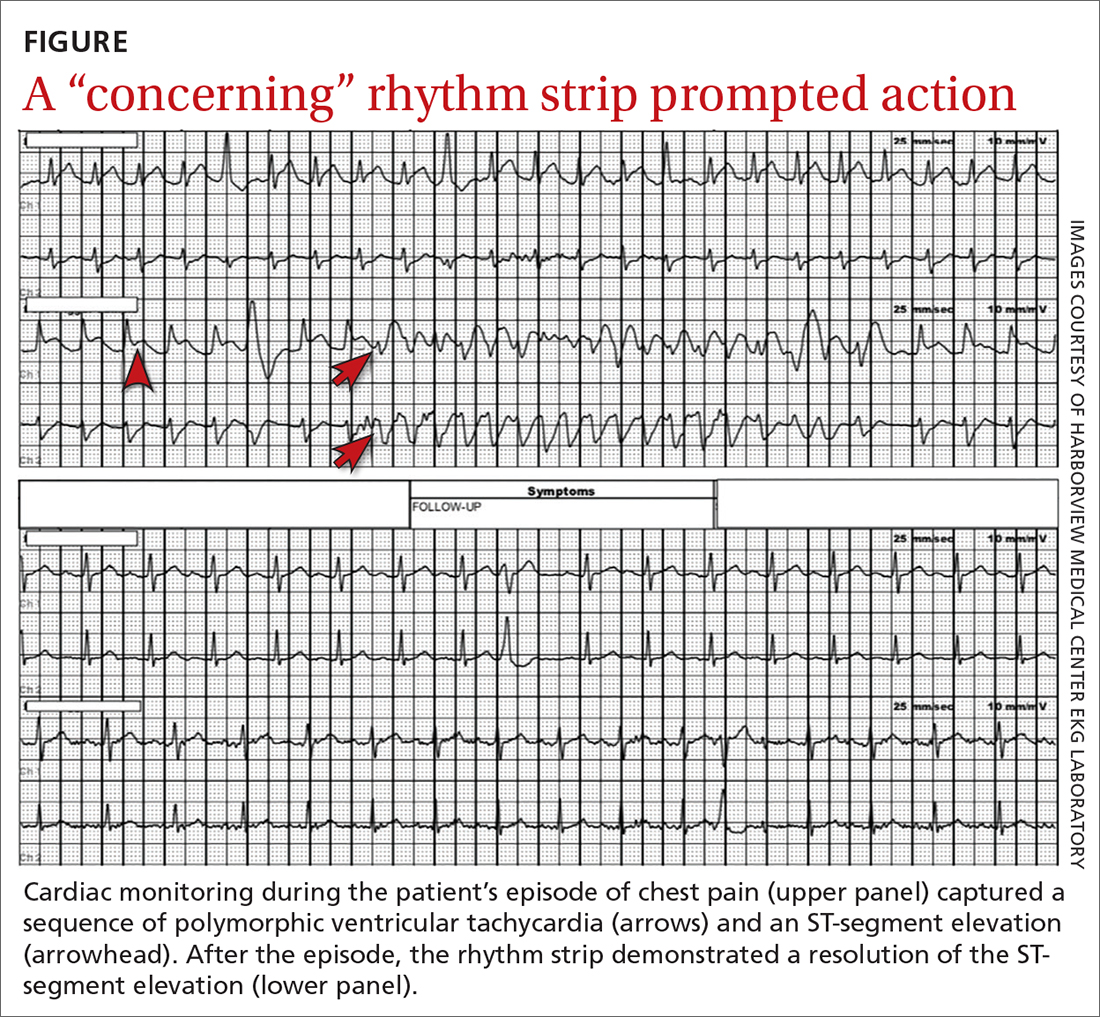

However, the rhythm monitoring company contacted the EKG lab to transmit a concerning strip (FIGURE). They also reported that the patient had been contacted and reported no further symptoms.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Most notable on the patient’s rhythm strip was a continuously varying QRS complex, which was indicative of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and consistent with the patient’s syncope and other symptoms. Less obvious at first glance was an ST-segment elevation in the preceding beats. Comparison to a post-episode tracing (FIGURE) highlights the abnormality. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia resolves in 1 of 2 ways: It will either stop on its own (causing syncope if it lasts more than a few seconds) or it will devolve into ventricular fibrillation, causing cardiac arrest.1

The combination of these findings and the clinical scenario prompted a recommendation that the patient report to the ED for admission (his wife drove him). He was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for continuous telemetry monitoring, and a cardiac catheterization was ordered. The procedure revealed a 99% thrombotic mid-right coronary artery lesion, for which aspiration thrombectomy and uncomplicated stenting were performed.

Continue to: DISCUSSION