Anxiety. As with other pain disorders, anxiety develops around pain triggers.10,15 When expecting sexual activity, patients can experience extreme worry and panic attacks.10,15,16 The distress of sexual encounters can interfere with physiologic arousal and sexual desire, impacting all phases of the sexual response cycle.1,2

Relationship issues. Difficulty engaging in or avoidance of sexual activity can interfere with romantic relationships.2,10,16 Severe pain or vaginismus contractions can prevent penetration, leading to unconsummated marriages and an inability to conceive through intercourse.10 The distress surrounding sexual encounters can precipitate erectile dysfunction in male partners, or partners may continue to demand sexual encounters despite the patient’s pain, further impacting the relationship and heightening sexual distress.10 These stressors have led to relationships ending, patients reluctantly agreeing to nonmonogamy to appease their partners, and patients avoiding relationships altogether.10,16

Devalued self-image. Difficulties with sexuality and relationships impact the self-image of patients with dyspareunia. Diminished self-image may include feeling “inadequate” as a woman and as a sexual partner, or feeling like a “failure.”16 Women with dyspareunia often have more distress related to their body image, physical appearance, and genital self-image than do women without genital pain.17 Feeling resentment toward their body, or feeling “ugly,” embarrassed, shamed, “broken,” and “useless” also contribute to increased depressive symptoms found in patients with dyspareunia.16,18

Making the diagnosis

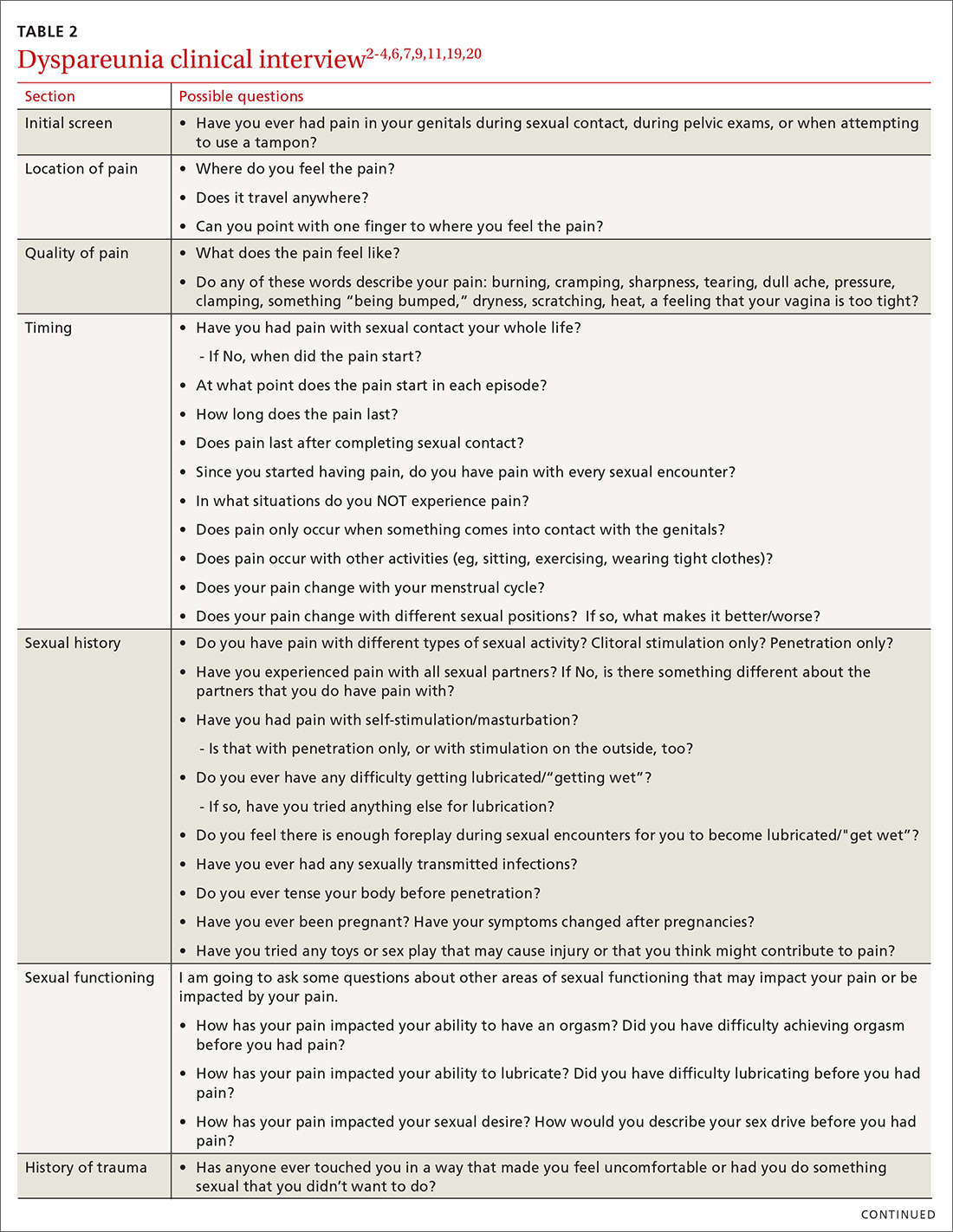

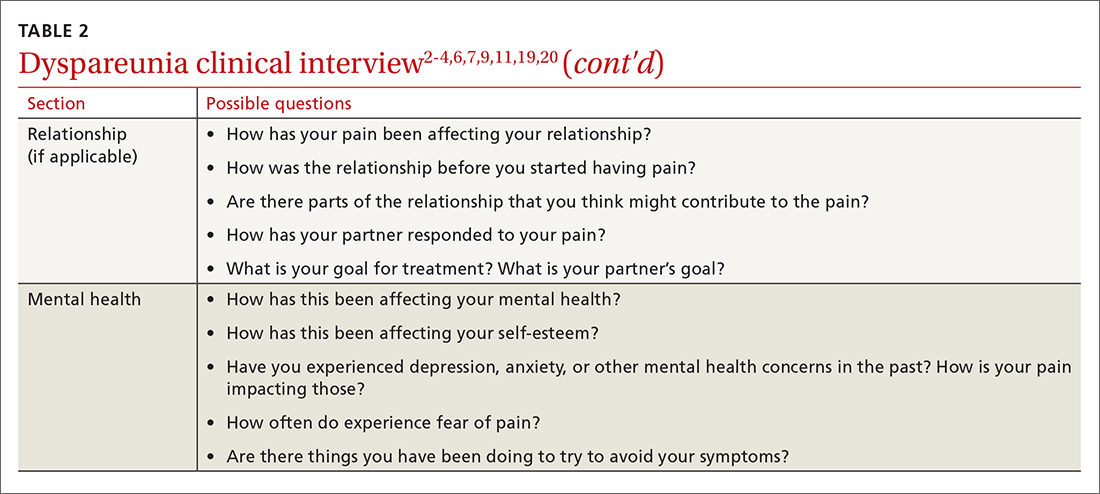

Most patients do not report symptoms unless directly asked2,7; therefore, it is recommended that all patients be screened as a part of an initial intake and before any genital exam (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20).4,7,21 If this screen is positive, a separate appointment may be needed for a thorough evaluation and before any attempt is made at a genital exam.4,7

Items to include in the clinical interview

Given the range of possible causes of dyspareunia and its contributing factors and symptoms, a thorough clinical interview is essential. Begin with a review of the patient’s complete medical and surgical history to identify possible known contributors to genital pain.4 Pregnancy history is of particular importance as the prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia is 35%, with risk being greater for patients who experienced dyspareunia symptoms before pregnancy.22

Knowing the location and quality of pain is important for differentiating between possible diagnoses, as is specifying dyspareunia as lifelong or acquired, superficial or deep, and primary or secondary.1-4,6 Confirm the specific location(s) of pain—eg, at the introitus, in the vestibule, on the labia, in the perineum, or near the clitoris.2,4,6 A diagram or model may be needed to help patients to localize pain.4

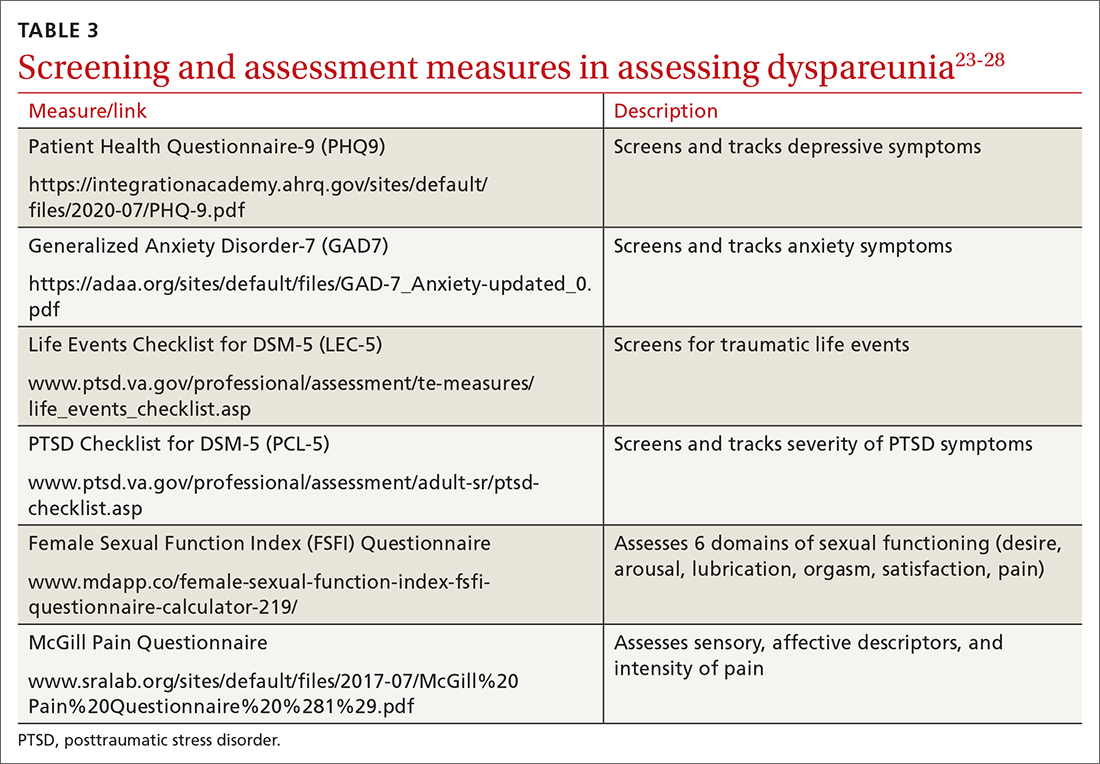

To help narrow the differential, include the following elements in your assessment: pain quality, timing (eg, initial onset, episode onset, episode duration, situational triggers), alleviating factors, symptoms in surrounding structures (eg, bladder, bowel, muscles, bones), sexual history, other areas of sexual functioning, history of psychological trauma, relationship effects, and mental health (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20 and Table 323-28). Screening for a history of sexual trauma is particularly important, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that women with a history of sexual assault had a 42% higher risk of gynecologic problems overall, a 74% higher risk of dyspareunia, and a 71% higher risk of vaginismus than women without a history of sexual assault.29 Using measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index or the McGill Pain Questionnaire can help patients more thoroughly describe their symptoms (TABLE 323-28).3

Continue to: Guidelines for the physical exam