Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

FM, the second most common disorder seen in rheumatologic practice after OA, is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 20 patients (approximately 5 million Americans) in the primary care setting.38,39 The condition has a high female-to-male preponderance (3.4% vs 0.5%).40 While the primary symptom of FM is chronic pain, patients commonly present with fatigue and sleep disturbance.41 Comorbid conditions include headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and mood disturbances (most commonly anxiety and depression).

Several studies have explored reasons for the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of FM. One important factor is ongoing skepticism among some physicians and the public, in general, as to whether FM is a real disease. This issue was addressed by a study by White and colleagues,42 who estimated and compared the point prevalence of FM and related disorders in Amish vs non-Amish adults. The authors hypothesized that if litigation and/or compensation availability have a major impact on FM prevalence, then there would be a near zero prevalence of FM in the Amish community. And yet, researchers found an overall age- and sex-adjusted FM prevalence of 7.3% (95% CI; 5.3%-9.7%); this was both statistically greater than zero (P < .0001) and greater than 2 control populations of non-Amish adults (both P < .05).

Many physicians consider FM fundamentally an emotional disturbance, and the high preponderance of FM in female patients may contribute to this misconception as reports of pain and emotional distress by women are often dismissed as hysteria.43 Physicians often explore the emotional aspects of FM, incorrectly diagnosing patients with depression and subsequently treating them with a psychotropic drug.39 Alternatively, they may focus on the musculoskeletal presentations of FM and prescribe analgesics or physical therapy, both of which do little to alleviate FM.

To make the correct diagnosis of FM, the American College of Rheumatology created a specific set of criteria in 1990, which was updated in 2010.44 For a diagnosis of FM, a patient must have at least a 3-month history of bilateral pain above and below the waist and along the axial skeletal spine. Although not included in the updated 2010 criteria, many clinicians continue to check for tender points, following the 1990 criteria requiring the presence of 11 of 18 points to make the diagnosis.

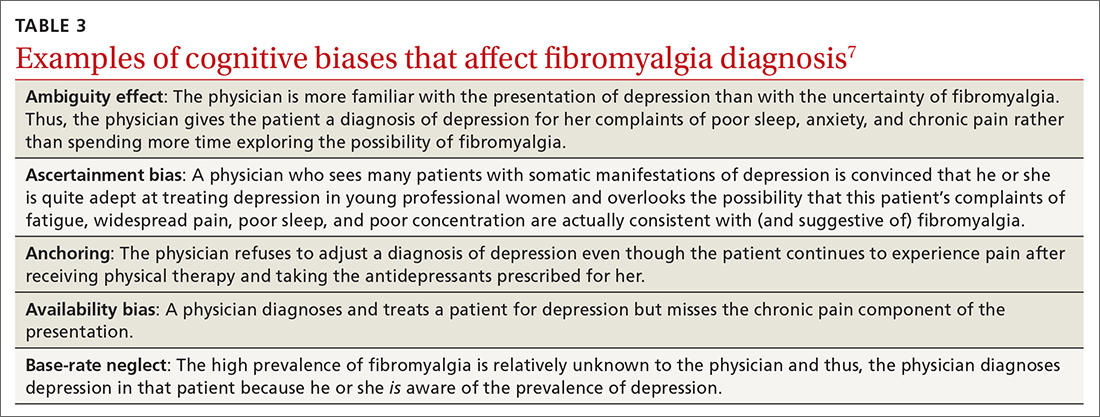

At least 3 cognitive biases relating to FM apply: anchoring, availability, and fundamental attribution error (see table 3).7 Anchoring occurs when the PCP settles on a psychiatric diagnosis of exaggerated pain syndrome, muscle overuse, or OA and fails to explore alternative etiology. Availability bias may obscure the true diagnosis of FM. Since PCPs see many patients with RA or OA, they may overlook or dismiss the possibility of FM. Attribution error happens when physicians dismiss the complaints of patients with FM as merely due to psychological distress, hysteria, or acting out.43

Patients with FM, who are often otherwise healthy, often present multiple times to the same PCP with a chief complaint of chronic pain. These repeat presentations can result in compassion fatigue and impact care. As Aloush and colleagues40 noted in their study, “FM patients were perceived as more difficult than RA patients, with a high level of concern and emotional response. A high proportion of physicians were reluctant to accept them because they feel emotional/psychological difficulties meeting and coping with these patients.”In response, patients with undiagnosed FM or inadequately treated FM may visit other PCPs, which may or may not result in a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We can do better

Primary care physicians face the daunting task of diagnosing and treating a wide range of common conditions while also trying to recognize less-common conditions with atypical presentations—all during a busy clinic workday. Nonetheless, we should strive to overcome internal (eg, cognitive bias and fund-of-knowledge deficits) and external (eg, time constraints, limited resources) pressures to improve diagnostic accuracy and care.

Each of the 4 disease states we’ve discussed have high rates of missed and/or delayed diagnosis. Each presents a unique set of confounders: PMR with its overlapping symptoms of many other rheumatologic diseases; OC with its often vague and misleading GI symptomatology; LBD with overlapping features of AD and Parkinson disease; and FM with skepticism. As gatekeepers to health care, it falls on PCPs to sort out these diagnostic dilemmas to avoid medical errors. Fundamental knowledge of each disease, its unique pathophysiology and symptoms, and varying presentations can be learned, internalized, and subsequently put into clinical practice to improve patient outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul D. Rosen MD, Brooklyn Hospital Center, Department of Family Medicine, 121 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11201; drpaulie2000@hotmail.com