Benzodiazepines (BZDs) and Z-hypnotics have been available for decades, yet uncertainties about their use remain. They are prescribed and overprescribed most often for anxiety and insomnia, for which they have value but also the potential for significant adverse consequences, notably physiologic dependence. Use of these agents should be limited, and planned deprescribing is a fundamental aspect of prescribing.

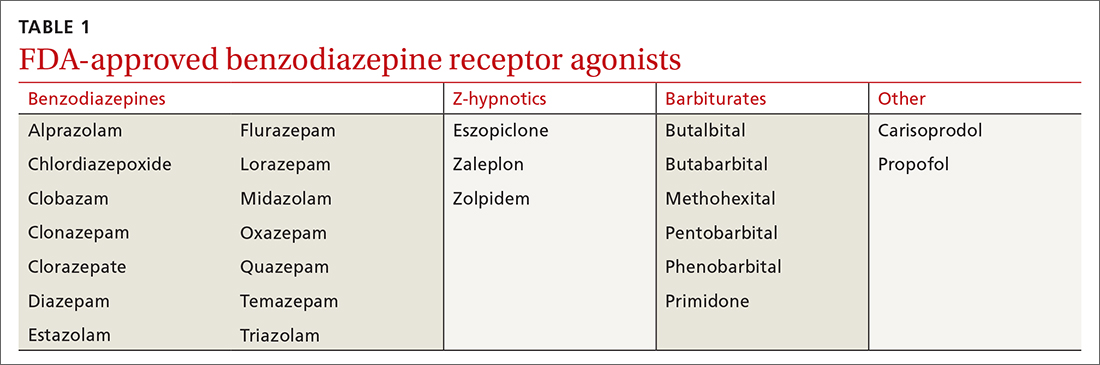

A brief history. BZDs are a subset of benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs), which enhance the inhibitory effect of centrally acting γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) at the GABAA receptor through allosteric modulation. In 1960, the first BZD, chlordiazepoxide, was marketed for clinical use, and as other agents in the class became available, BZDs supplanted the more toxic barbiturates, another BZRA subset (TABLE 1). By the late 1970s, BZDs had risen to the top of most prescribed medications, with one agent in particular—diazepam (Valium)—earning a reputation as “mother’s little helper,” a phrase derived from a Rolling Stones' song with that title produced in 1966.1

With recognition of the problems associated with BZDs, their popularity diminished somewhat but remained high. BZDs were listed under Schedule IV by the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1975 due to the risk for addiction, and on the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria list in 1991 because of significant adverse consequences in the elderly. Researchers began to question their use as early as the 1970s, and the landmark Ashton Manual, guidance for patients and clinicians alike, was published in 2002.2

Currently, there are 14 BZDs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as well as 3 Z-hypnotics, termed such as they include the letter “z” in their generic names (TABLE 1). In recent years, BZD prescribing has risen; a 2019 study found that 1 of 8 American adults reported using a BZD in the previous year.3

Limited benefits of benzodiazepine receptor agonists

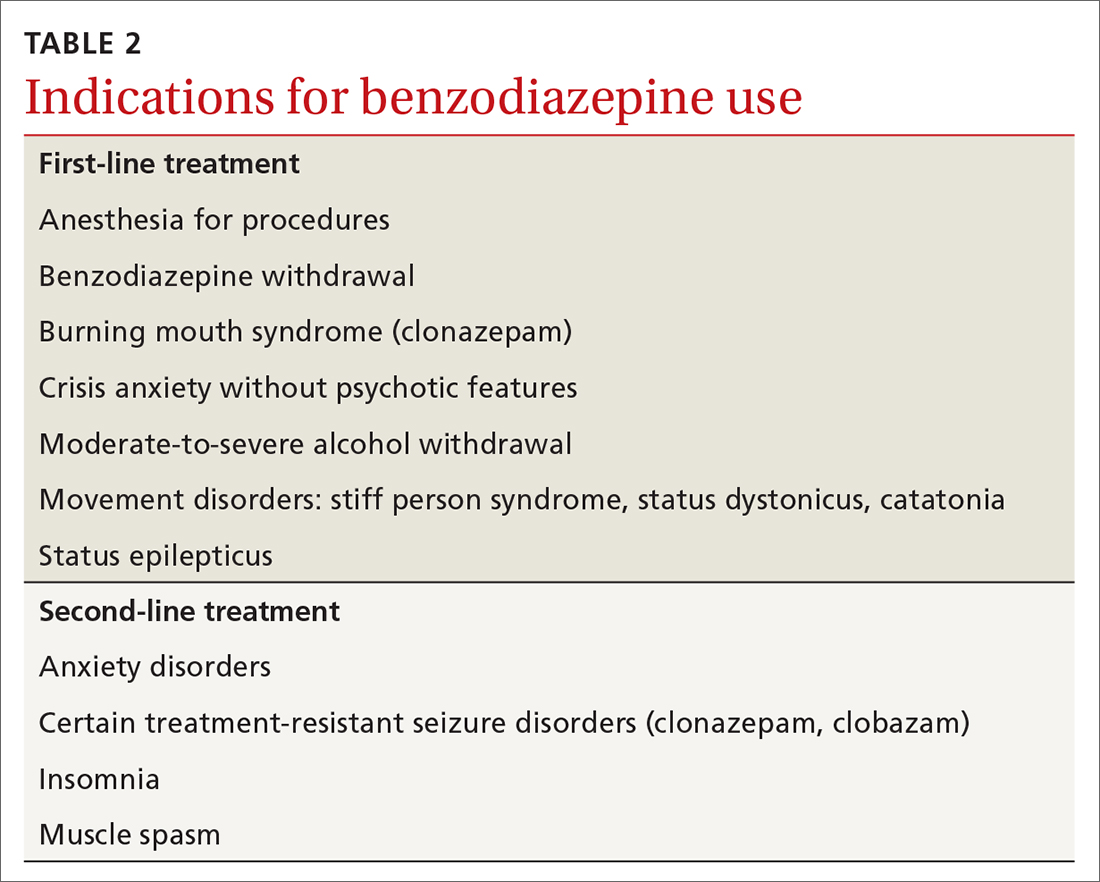

BZRAs can be of benefit in a limited range of medical conditions, including some for which they are first-line considerations. (See TABLE 2 for a list of indications for BZDs.) They are most often prescribed for anxiety and insomnia, although they are not first-line treatments for these conditions and should be prescribed only when symptoms limit a patient’s daily functioning.

BZRAs are not intended for long-term use. In recent decades, the percentage of patients prescribed BZRAs has doubled, and more than 80% of these patients indicate usage for more than 6 months.4 Evidence, however, does not support long-term daily use.

Observation periods in most studies are far shorter than the number of years over which BZDs are actually prescribed, and flawed research methodology has introduced the risk of bias. Specifically, the generalizability of reported outcomes must be qualified, since efficacy trials performed under ideal study conditions (eg, exclusion criteria to minimize confounders) differ from circumstances seen in clinical practice. Conclusions are also limited by the inherent bias of pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and unavailability of unpublished trials that may have demonstrated unfavorable results.

Continue to: Insomnia