Three conditions seen in primary care—gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection, and Barrett esophagus (BE)—evolve in a gastric acid environment and are treated in part through gastric acid suppression. While GERD is a risk factor for the development of BE, H pylori is not associated with BE.1 Patients with H pylori are actually less likely to have GERD symptoms.2,3 In this article, we describe similarities and differences in patient presentations, diagnostic testing, and management, and review screening recommendations.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

GERD is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms of regurgitation and heartburn or the presence of one of its known complications (esophagitis, peptic strictures, or BE).2,4 Chest pain is also common. Atypical symptoms are dysphagia, bleeding, chronic cough, asthma, chronic laryngitis, hoarseness, wheezing, teeth erosions, belching, and bloating.2,5-7

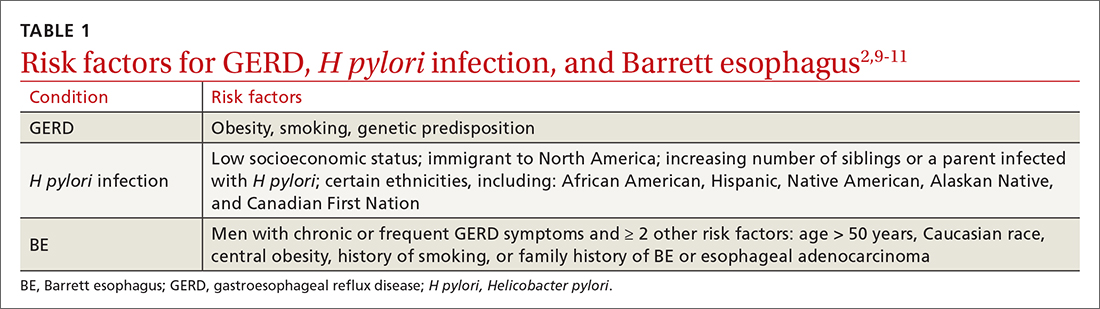

The worldwide prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in adults is 14.8%.8 When using a stringent definition of GERD—weekly symptoms occurring for at least 3 months—prevalence drops to 9.4%.9 GERD symptoms vary markedly by geographic location; the highest rates are in Central America (19.6%) and the lowest rates are in Southeast Asia (7.4%).8TABLE 12,9-11 lists risk factors for GERD.

GERD results from dysfunction of the esophagogastric junction that permits regurgitation of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus. Normally, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxes temporarily with gastric distention; when this relaxation is frequent and prolonged, it causes GERD.2,12 Several medications, particularly those with anticholinergic effects (eg, tricyclic antidepressants) can decrease LES tone and contribute to symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often linked to dyspepsia and gastritis and should be avoided in patients who have symptoms of GERD. Pathologic reflux can also occur in conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as obesity and pregnancy, and with esophageal dysmotility, hiatal hernia, and delayed gastric emptying.5 When gastric contents travel proximally, this contributes to extraesophageal symptoms, such as chronic cough, asthma, laryngitis, dyspepsia, bloating, and belching.2,4

Treatment

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most effective treatment for GERD, but lifestyle modifications are also recommended for all patients.2,6,13-16 Consider selective elimination of beverages and foods that are commonly associated with heartburn (eg, alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, citrus, and spicy foods) if patients note a correlation to symptoms.5,6,13 Also, advise weight loss and smoking cessation, as appropriate, and suggest that the patient elevate the head of their bed when sleeping.

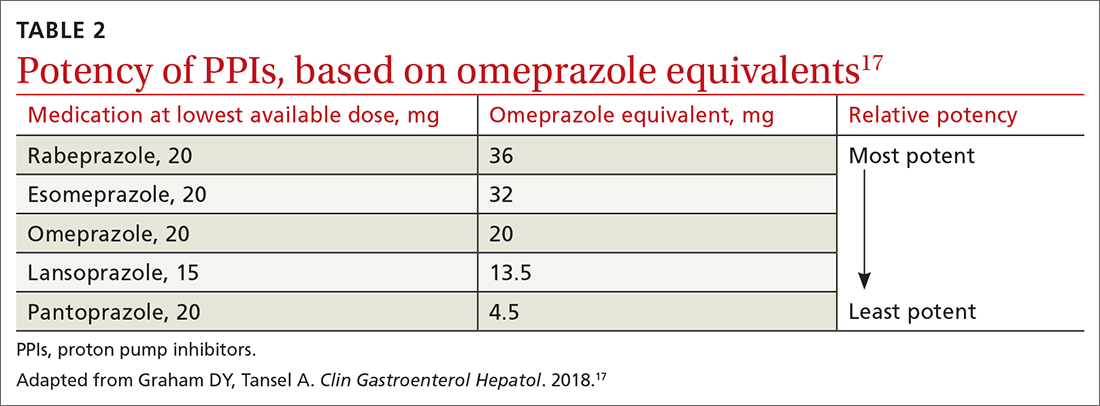

All PPIs are equally effective in suppressing acid when given at equivalent doses (TABLE 217), so they can be used interchangeably.17 Treat uncomplicated GERD with a once-daily PPI 30 to 60 minutes prior to a meal for 4 to 8 weeks. If treatment is effective, you’ll want to try to reduce or stop the medication after the 4- to 8-week period. (It’s worth noting that the benefits of treatment for those with extraesophageal GERD are less predictable than for those with heartburn or esophagitis symptoms.5)

If GERD symptoms reemerge after the PPI is stopped, the medication can be restarted but should be limited to the least potent effective dose, no matter if it is taken daily or only as needed.2,6,17 In patients with esophagitis, you may need to continue PPI treatment indefinitely at the lowest possible dose given the increased risk of recurrent esophagitis.2,13,16

Continue to: Keep in mind...