Is there evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease?

Initial screening can be completed by obtaining the patient’s history and conducting a physical examination. Patients reporting chest pain or discomfort (or any anginal equivalent), dyspnea, syncope, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, signs of tachyarrhythmia/bradyarrhythmia, intermittent claudication, exertional fatigue, or new exertional symptoms should all be considered for cardiovascular stress testing. Patients with a diagnosis of renal disease or either type 1 or type 2 diabetes should also be considered for cardiovascular stress testing.

Ready to prescribe exercise? Cover these 4 points

When prescribing any exercise plan for older adults, it is important for clinicians to specify 4 key components: frequency, intensity, time, and type (this can be remembered using the acronym “FITT”).23 A sedentary adult should be encouraged to engage in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, for 15 minutes 3 times per week. The key with a sedentary adult is appropriate follow-up to monitor progression and modify activity to help ensure the patient can achieve the goal number of minutes per week. It can be helpful to share the “next step” with the patient, as well (eg, increase to 4 times per week after 2 weeks, or increase by 5 minutes every week). For the intermittent exerciser, a program of moderate exercise, such as using an elliptical, for 30 to 40 minutes 5 times per week is a recommended prescription. FITT components can be tailored to meet individual patient physical readiness.23

Frequency. While the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a specific frequency of physical activity throughout the week, it is important to remember that some older adults will be unable to meet these recommendations, particularly in the setting of frailty and comorbidities (TABLE 22). In these cases, the guidelines simply recommend that older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and comorbidities allow. Some exercise is better than none, and generally moving more and sitting less will yield health benefits for older adult patients.

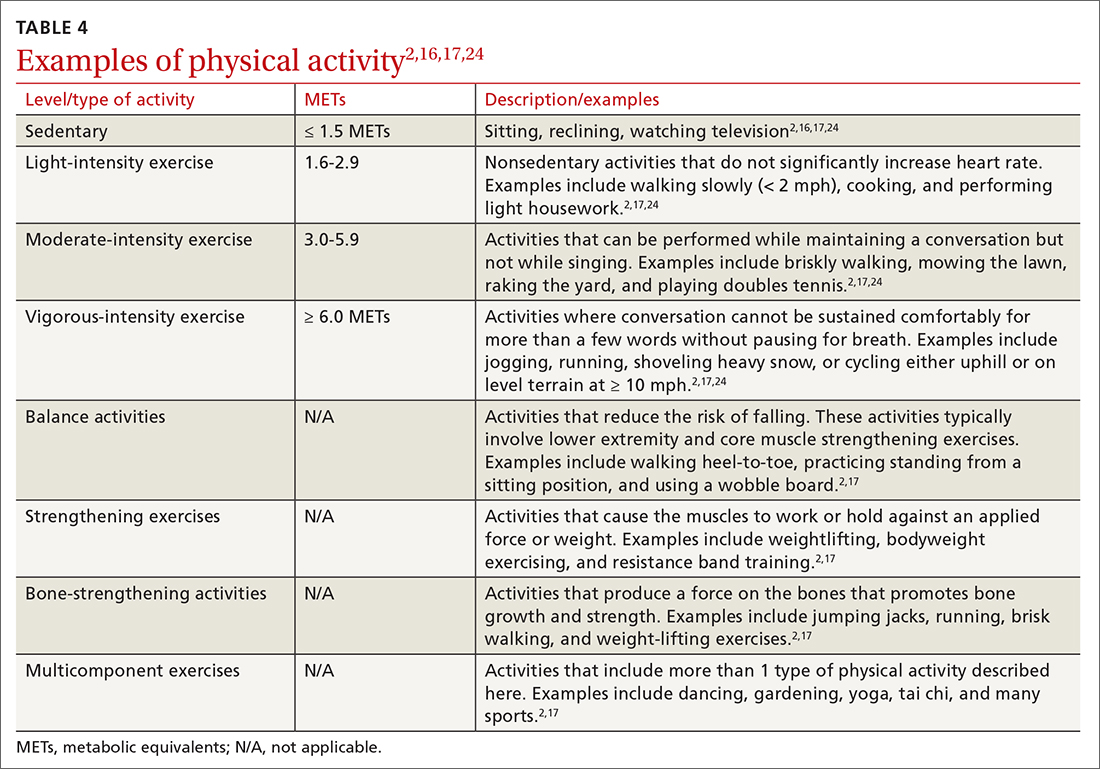

Intensity is a description of how hard an individual is working during physical activity. An older adult’s individual capacity for exercise intensity will depend on many factors, including their comorbidities. An activity’s intensity will be relative to a person’s unique level of fitness. Given this heterogeneity, exercise prescriptions should be tailored to the individual. Light-intensity exercise generally causes a slight increase in pulse and respiratory rate, moderate-intensity exercise causes a noticeable increase in pulse and respiratory rate, and vigorous-intensity exercise causes a significant increase in pulse and respiratory rate (TABLE 42,16,17,24).2

The “talk test” is a simple, practical, and validated test that can help one determine an individual’s capacity for moderate- or vigorous-intensity exercise.23 In general, a person performing vigorous-intensity exercise will be unable to talk comfortably during activity for more than a few words without pausing for breath. Similarly, a person will be able to talk but not sing comfortably during moderate-intensity exercise.3,23

Continue to: Time