Nearly 40 antihyperglycemic agents have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since the approval of human insulin in 1982.1 In addition, existing antihyperglycemic medications are constantly gaining FDA approval for new indications for common type 2 diabetes (T2D) comorbidities. For example, in addition to their glycemic benefits, the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have been approved for use in patients with T2D and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to reduce the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; canagliflozin), risk for hospitalization for heart failure (dapagliflozin), and cardiovascular death (empagliflozin).2-4

The plethora of new agents and new data for existing agents, coupled with the annual release of guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and practice recommendations from several other professional organizations,5-7 make it challenging for family physicians to stay current and provide the most up-to-date, evidence-based care. In this article, we provide advice on how to approach the screening, diagnosis, and evaluation of T2D, and on how to manage newly diagnosed T2D.

Screening, Dx, and evaluation: A quick review

Screening

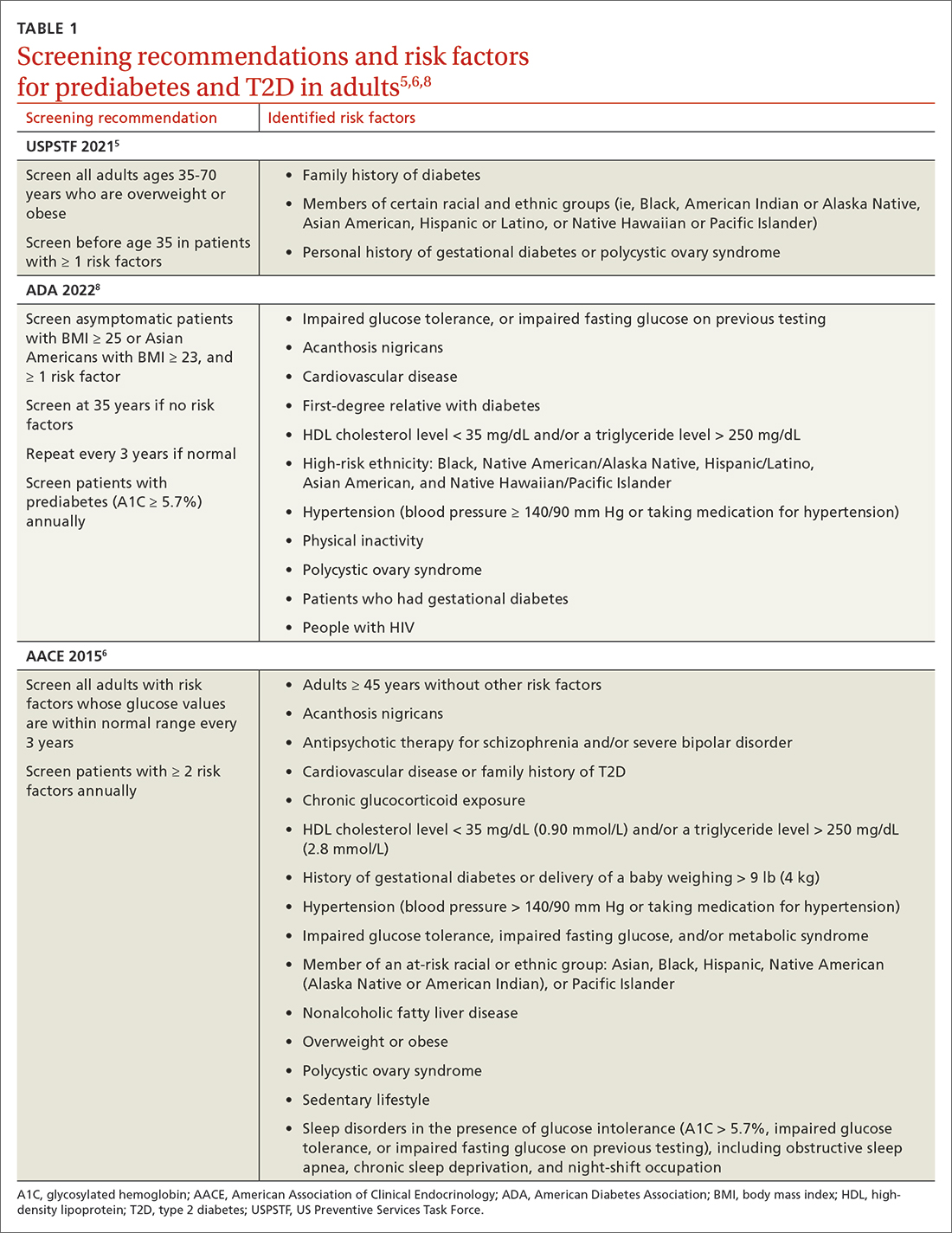

Screening recommendations vary among professional organizations (TABLE 15,6,8). The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese. Clinicians also can consider screening patients with a higher risk for diabetes.5 The ADA suggests screening all adults starting at 35 years, regardless of risk factors.8 Asymptomatic adults of any age with overweight or obesity and 1 or more risk factors should be screened.8 The American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) recommends screening adults of any age who have risk factors.6 If the screening result is normal, repeat testing in 3 years is appropriate, unless there is a change in symptoms or risks.5,8 Annual testing can be considered in patients with ≥ 2 risk factors or with prediabetes (glycosylated hemoglobin [A1C] ≥ 5.7%).6,8

Making the diagnosis

The initial diagnosis of diabetes can be made by a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L); a 2-hour plasma glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.0 mmol/L) following an oral glucose tolerance test; or an A1C level ≥ 6.5%. Prioritize lab-drawn A1C measurements over point-of-care tests to diagnose T2D. In patients with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia, a random plasma glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.0 mmol/L) is also diagnostic. Generally, these tests are considered equally appropriate in screening for diabetes and may be used to detect prediabetes. In the absence of clear symptoms of hyperglycemia, the diagnosis of diabetes requires 2 abnormal screening test results, either via 1 blood sample (such as an abnormal A1C and glucose) or 2 separate blood samples of the same test. Further evaluation is advised if there is discordance between the 2 samples.8

Extended evaluations

Patients with newly diagnosed T2D require a thorough evaluation for comorbidities and complications of diabetes. Refer patients to an ophthalmologist for a dilated eye examination, with subsequent exams occurring every 1 to 2 years.6,9 Additional referrals for diabetes education, family planning for women of reproductive age, and dental, social, or mental health services may be clinically appropriate.9

Setting goals for glycemic control

Glycemic control is commonly monitored by the A1C level and by blood glucose monitoring either through traditional point-of-care glucometers or continuous glucose monitors (CGMs).10 Generally, CGMs provide more glycemic data than traditional glucometers and may cue patients to choose healthier dietary options and engage in physical exercise.11 Patients with T2D who use CGMs exhibit lower A1Cs, greater time in glycemic range, and reduced hypoglycemic episodes.11 Generally, CGMs are reserved for patients with type 1 diabetes and patients with T2D who use multiple daily injections, subcutaneous insulin infusions, or basal insulin only.12 Most professional organizations recommend that clinicians consider patient-specific factors to set individualized glycemic goals.6,10,13,14 For example, more stringent glycemic goals could be pursued for patients with longer life expectancy, shorter disease duration, absence of complications (eg, nephropathy, neuropathy, or cardiovascular disease), fewer comorbid conditions, lower hypoglycemia risk, or higher cognitive function.6

More specific A1C goals vary by professional organization. For nonpregnant adults, the ADA recommends an A1C goal of < 7% and a preprandial blood glucose level of 80 to 130 mg/dL (4.4-7.2 mmol/L).10 However, a lower A1C goal may be appropriate if it can be attained safely without causing hypoglycemia or other adverse effects.10 The AACE suggests an A1C goal of ≤ 6.5% and a fasting blood glucose level of < 110 mg/dL when it can be achieved safely.6 More stringent A1C goals may reduce long-term micro- and macrovascular complications—especially in patients with newly diagnosed T2D.10 While older studies such as the ACCORD trial found increased mortality in groups with more stringent glycemic targets, they did not include newer agents (SGLT2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] receptor agonists) that reduce cardiovascular events by mechanisms outside their glycemic-lowering effect. With these newer agents, more aggressive A1C goals can be targeted safely in select patients, particularly those with long life expectancy.10 Both the ADA and AACE recommend a less stringent A1C goal of 7% to 8% for patients with limited life expectancy or risks (eg, a history of hypoglycemia) that outweigh expected benefits.6,10

Continue to: Lifestyle modifications