The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

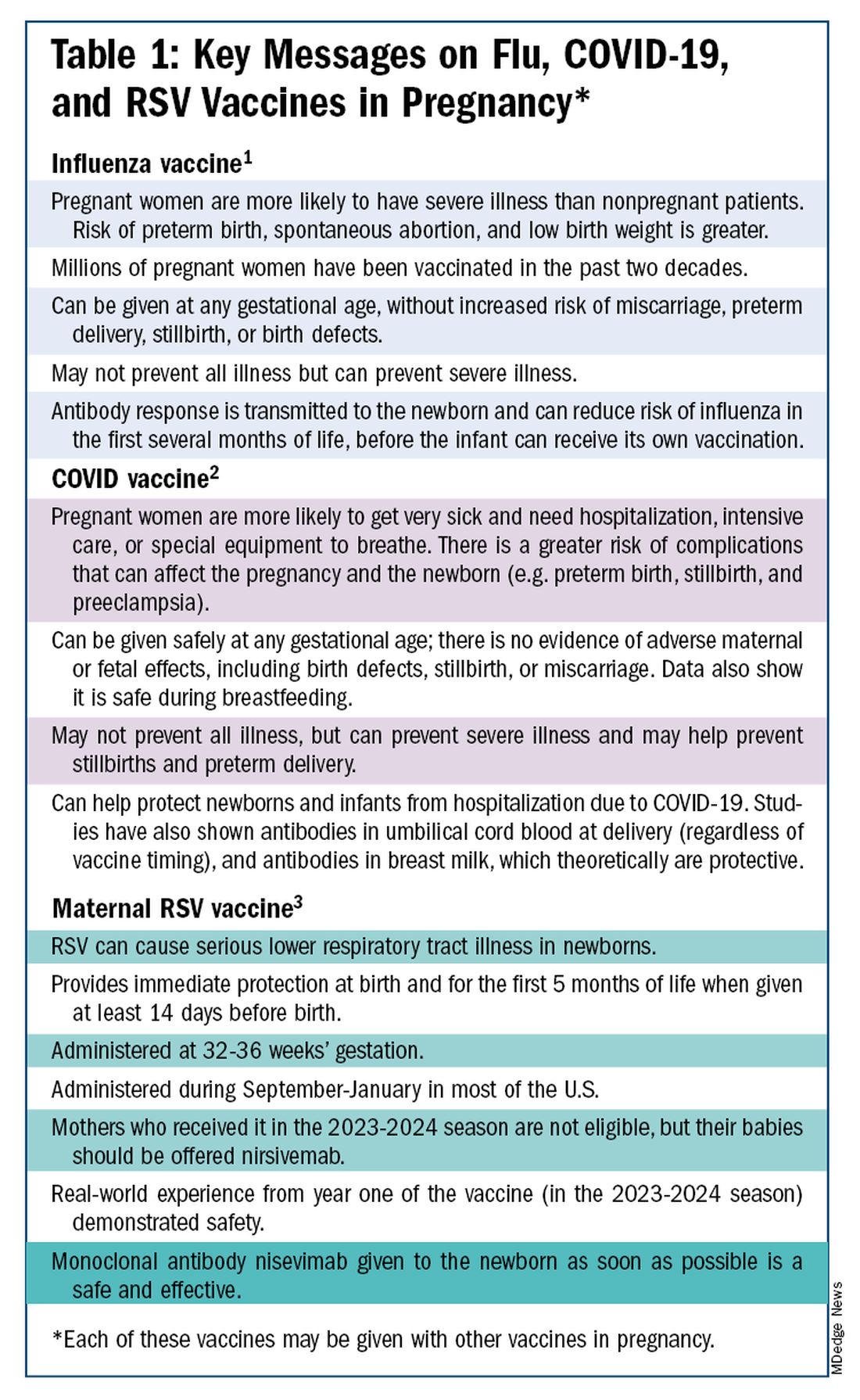

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

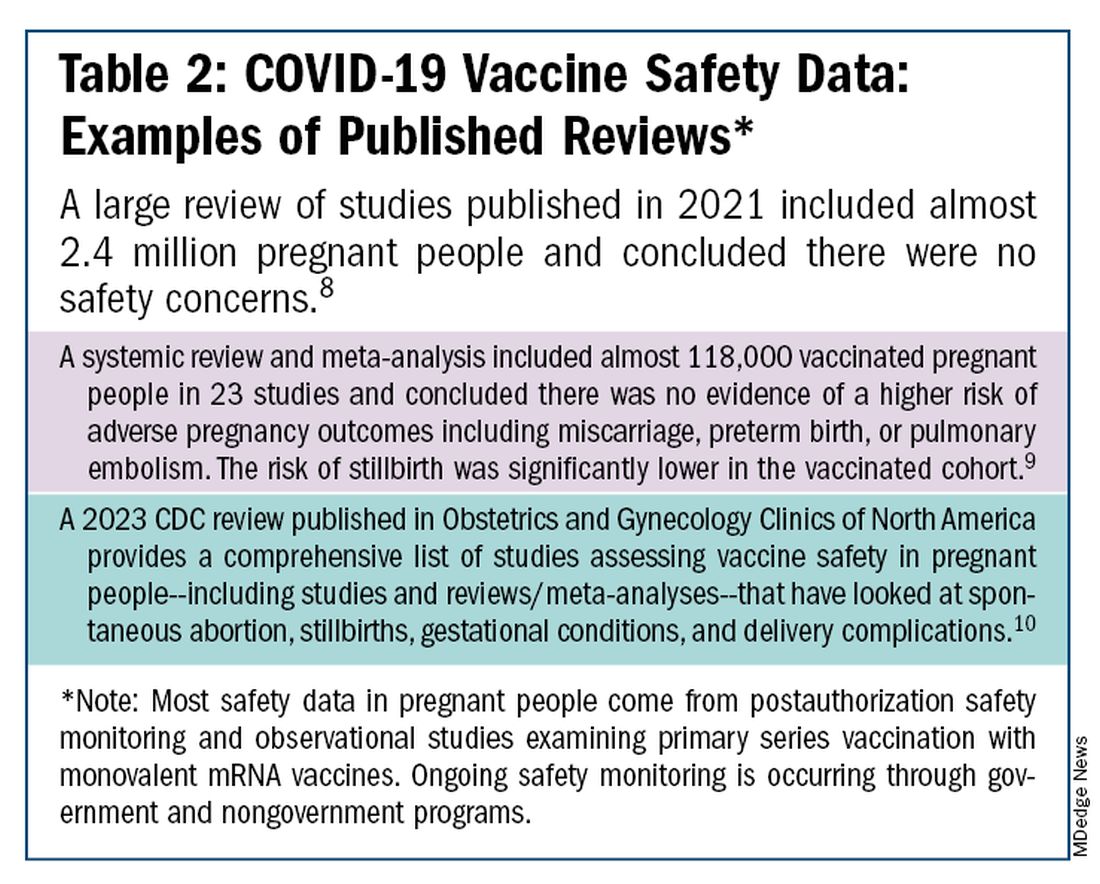

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.