DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

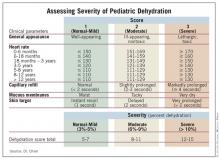

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.