There are tools that can be used to screen patients for risk. Among those are the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients With Pain (SOAPP); the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT); the Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk Efficacy (DIRE) test; and the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM), which is used for patients already taking opioids.

These tests all are simple and take only 1 to 10 minutes to administer. They can be given by any physician, including primary care physicians, he said.

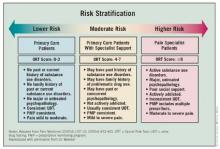

Once all the factors are taken into account, patients can be stratified according to risk. Lower-risk patients – those with moderate pain and no personal or family history of substance use disorders – can be managed by primary care physicians. Those at moderate risk may need the addition of a pain specialist. The higher-risk patients will need consultations with mental health professionals and pain physicians.

Monitoring higher-risk patients may require urine drug testing and prescription monitoring programs. Pharmacists should be kept in the loop to see whether patients are shopping around. Family and friends can be invaluable sources to help identify risky behaviors.

Physicians need to do a better job of titrating opioids and determining proper dosing. Many patients have died at initiation of opioid therapy, or from rotating from one drug to another, he said. Patients should not be allowed to determine how much of a long-acting medication they can take.

So how do doctors mitigate risk? The first order of business is to treat the pain. "Uncontrolled pain, untreated pain, I believe is the number one reason for aberrant behavior," said Dr. Webster. Physicians cannot eliminate all pain, however, so education also is crucial.

Physicians also have a duty to monitor pain patients. "You don’t just put someone on an opioid and think you’ve done your job," said Dr. Webster. A doctor would not stop managing a diabetic; pain patients need long-term management, he said.

Dr. Webster reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.