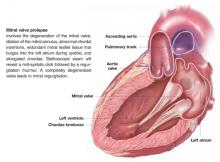

Patients with suspected mitral valve prolapse (MVP) ( Figure 1 ) should undergo echocardiography before any procedure that may place them at risk for bacteremia. Patients with MVP and documented absence of mitral regurgitation or valvular thickening likely do not need antibiotic prophylaxis against subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). Patients with MVP with documented mitral regurgitation, valvular thickening, or an unknown degree of valvular dysfunction may benefit from antibiotics during procedures that often lead to bacteremia (strength of recommendation: C).1

FIGURE 1 Mitral valve prolapse

Evidence summary

Only disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion address prevention for endocarditis. A randomized trial would require an estimated 6000 patients to demonstrate benefit.2

Endocarditis occurs in MVP at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 patient-years.3 However, MVP is the most common predisposing/precipitating cause of native valve endocarditis.4,5 In animal models, antibiotics prevent endocarditis following experimental bacteremia. The antibiotic can be administered either just before or up to 2 hours after the bacteremic event.2 It is worth noting that most bacteremia is not associated with medical procedures. Since endocarditis is often fatal, recommendations have been developed based on these animal models. Estimates of effectiveness of prophylaxis from case-control studies in humans (not limited to patients with MVP) estimate effectiveness from 49% to 91%.2

For patients with MVP who do not have evidence of mitral regurgitation on physical examination or echocardiography, the risk of morbidity may be greater from antibiotic therapy than the risk of endocarditis. Prophylaxis for these patients is not recommended. Patients with MVP associated with regurgitation are at moderate risk and may benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis.

Recommendations from others

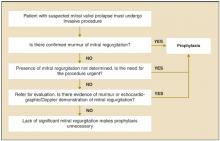

The American Heart Association has published recommendations in 1985,6 1990,7 and 1997.1 The 1997 recommendations are summarized in Figure 2 . The Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis published similar recommendations in 2000.8 Recommended prophylactic regimens appear in Table 1. Table 2 shows a modified list of procedures for which prophylaxis is recommended.

FIGURE 2

Determining the need for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with mitral valve prolapse

TABLE 1

Recommended prophylactic regimens for mitral valve prolaspe

| Situation | Medication | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental, oral, respiratory, esophageal procedures | 1 hour before procedure | ||

| Standard prophylaxis | Amoxicillin | Adult:2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| Allergy to penicillin | Clindamycin | Adult: 600 mg | Child: 20 mg/kg |

| Cephalexin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg | |

| Azithromycin | Adult: 500 mg | Child: 15 mg/kg | |

| Genitourinary or non-esophageal gastrointestinal procedures | |||

| Moderate-risk patients | Amoxicillin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| 1 hour before procedure | |||

| Moderate-risk patients allergic to penicillin | Vancomycin | Adult: 1 g IV | Child: 20 mg/kg IV |

| Administer over 1-2 hrs; complete 30 minutes before procedure | |||

| High-risk patients | Add gentamicin to amoxicillin or vancomycin | 1.5 mg/kg (up to 120 mg) IV to be completed 30 minutes before procedure. If not allergic to penicillin, give penicillin give penicillin, give amoxicillin 1 g 6 hours after | |

| Modified from Dajani 1997.1 | |||

TABLE 2

Procedures for which endocarditis prophylaxis is, or is not, recommended

| Endocarditis prophylaxis recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy |

| Surgical operations that involve respiratory mucosa |

| Bronchoscopy with a rigid bronchoscope |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices |

| Esophageal stricture dilation |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with biliary obstruction |

| Biliary tract surgery |

| Surgical operations that involve intestinal mucosa |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Prostatic surgery |

| Cystoscopy |

| Urethral dilation |

| Endocarditis prophylaxis not recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Endotracheal intubation |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, with or without biopsy |

| Tympanostomy tube insertion |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Endoscopy with or without gastrointestinal biopsy |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Circumcision |

| Vaginal hysterectomy |

| Vaginal delivery |

| Cesarean section |

| In uninfected tissue |

| Incision or biopsy of surgically scrubbed skin |

| Urethral catheterization |

| Uterine dilatation and curettage |

| Therapeutic abortion |

| Sterilization procedures |

| Insertion or removal of intrauterine devices |

| Cardiac |

| Transesophageal echocardiography |

| Cardiac catheterization, including balloon angioplasty and coronary stents |

| Implanted cardiac pacemakers, implanted defibrillators |

| Modified from Dajani et al, 1997.1 |

Guidelines assist decision-making regarding who needs SBE prophylaxis

David M. Bercaw, MD

Christiana Care Health Systems, Wilmington, Del

It is unfortunate, but not surprising, that the evidence for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP is disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion. Too often, the easy thing to do in a busy practice is not necessarily in the best interest of either the patient or the public. However—despite the low incidence of SBE—the high mortality of the disease and community standard of care often drive clinicians to write that prescription for antibiotics.

With the improved resolution and sensitivity of newer generations of echocardiograms, clinicians often face the dilemma of the patient with MVP and “trivial” or “mnimal” mitral regurgitation. Unfortunately, no guidelines assist us in our decision-making regarding these patients. Another consideration for the clinician is the American Heart Association’s recommendation for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP and thickened leaflets, regardless of whether there is associated mitral valve regurgitation.

One significant change that should lessen the frequency of unnecessary antibiotic prescribing was published recently. The echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing MVP were changed in the 2003 updated guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American Society of Echocardiography. Valve prolapse of 2 mm or more above the mitral annulus is required for diagnosis.10 This change has effectively lowered the prevalence of MVP from 4% to 8% of the general population down to 2% to 3%.