Q: Why might you and the house staff have been vague about the cause of the hypoglycemia? What should you say now?

A:_____________________________________________________

Discussing prescribing errors is uncomfortable. In this instance, you the primary doctor may have been reluctant because your office appeared to be most responsible for the mistake. And the residents also may have been reluctant to say anything that might appear critical of the primary doctor’s office. Evidence suggests that most physicians prefer not to discuss the details of errors or even to use the term “error.” They prefer less emotive language.15 In contrast, there is some evidence to suggest that patients and families would like to be informed when an error occurs in their care.15,18

As the primary care physician discovered in this case, correcting a medication error often depends on informing the patient. The negative impacts of disclosure (including the possibility of litigation and other sanctions, and the potential for loss of trust) are the subject of much debate.19-21

Ultimately, the decision to disclose an error must be based on risks and benefits to both patient and physician. If you decide to disclose, choose words carefully. And be careful to avoid apportioning blame. As this case illustrates, adverse events can have many contributing factors, and, in most cases, further investigation is required before a full explanation can be given. Therefore it is generally recommended that when disclosure is made, you should limit the discussion to the known facts. Further disclosure can always be made at a later date if warranted, when more objective information is available.

FIGURE 2 Hospital discharge instructions

A closer examination of what went wrong

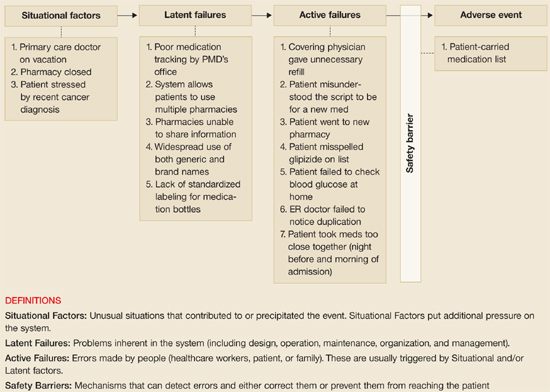

In this case, unusual situations, system problems, and errors by individuals combined to cause recurrent hypoglycemia and unnecessary hospitalization. James Reason has provided a framework in which a case such as this may be analyzed systematically. It is called the Adverse Event Trajectory,22 and its application to this case is depicted in FIGURE 3. Each contributing factor is categorized according to the framework and written onto the diagram in such a way as to provide a summary of the whole event. This format has been used successfully as a teaching tool for family medicine residents.23

The main advantage of this analysis is that it clearly separates human errors (Active Failures) and system problems (Latent Failures, and the lack of Safety Barriers). Often, human error is chiefly blamed for adverse events and little effort is made to look beyond this. However, if we accept that “to err is human”24 and that most errors have roots in systemic problems, then the Adverse Event Trajectory framework can focus our attention on areas more likely to yield workable solutions.

Preventing recurrent errors usually is best assured by (1) correcting latent failures and (2) creating effective safety barriers. The strategies in TABLE 2 that involve changing systems (such as implementing electronic prescribing as part of an electronic medical record) are more likely to be effective than those that change behavior only (such as encouraging patients to use one pharmacy exclusively). However, system strategies also tend to be more expensive and difficult to implement than the latter. Perhaps it is most appropriate to use a combination of approaches listed in TABLE 2.

As implied under “Safety Barriers” in FIGURE 3, an effective patient-carried medication list had the potential to protect this patient from harm. Possible strategies for implementing such a barrier have been discussed above.

Items 2 and 3 under “Latent Failures” apply to the pharmacy level, and solutions would likely require legislation. Restricting access to one pharmacy exclusively would probably have prevented the duplication in our case. However, if such restriction were enforced unilaterally by a payer, it could make that payer less competitive since patients may value the freedom of changing pharmacies at will.

A more realistic alternative is to give pharmacies access to one another’s databases or even to create a central database to which all pharmacies would have access, with the patient’s permission. Clearly confidentiality issues would need to be addressed before such a program was implemented. And there would likely be opposition from the large pharmacy chains who might see this approach as a threat.

FIGURE 3 Adverse event trajectory: Breaking down the process into revealing components

The value of this analytic technique is in identifying and categorizing all factors (not just human error) that potentially contribute to untoward events. Efforts aimed at correcting or improving factors under “Latent Failures” or “Safety Barriers” are usually most fruitful.