Rule out structural causes

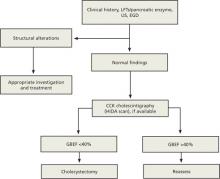

There is no single test for FGBD, and a definitive diagnosis can be made only after structural causes of the symptoms (eg, gallstones, tumor, sclerosis, and cirrhosis) have been ruled out (ALGORITHM).2 Initial tests include liver and pancreatic enzyme laboratory screening and an ultrasound of the upper right quadrant. In patients with FGBD, both the lab tests and the ultrasound will be normal.

ALGORITHM

Diagnostic workup and management of functional gallbladder disorder (Rome III)

CCK, cholecystokinin; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GBEF, gallbladder ejection fraction; HIDA, hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid; LFTs, liver function tests; US, ultrasound.

Source: Behar J et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1498-1509.2 Used with permission from Elsevier.

The Rome III guidelines also call for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out esophagitis, gastritis, and duodenitis, although some researchers have held that if the other tests are normal, this test need not be done.12 If the EGD is also normal—or not done—a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan is the next step in the diagnostic pathway. The scan tests the gallbladder’s ejection fraction (EF), revealing the percentage of radioactive dye ejected from the organ after CCK is injected (FIGURE).2 The injection of CCK should be done over a minimum of 30 minutes, the guidelines specify. The shorter the time frame used for the injection, the less likely that the pain will be reproduced or that the EF findings will be reliable.14

FIGURE

Abnormal vs normal HIDA scans: What you’ll see

The larger amount of contrast dye retained in the abnormal scan (A) compared with the normal scan (B) is evidence of a poor ejection fraction.

Most researchers define a normal EF as >35%,10,11,13 but the Rome III criteria use a cutoff of 40%. A patient who has an EF <40% and meets the other guideline criteria is diagnosed with FGBD.

CASE On physical examination, Ms. J has pain in the right upper quadrant, with no guarding or rebound, and normal bowel sounds. Her liver and pancreatic enzyme tests are normal, and an ultrasound shows no sludge, no stones, and mild edema of the gallbladder wall. The patient declines an EGD because of the cost but undergoes a HIDA scan—which reveals that she has an EF of 25%.

Will cholecystectomy bring long-term relief?

There are 2 options for a patient diagnosed with FGBD—medical management, consisting of lifestyle modifications such as dietary change and weight loss and medication for symptom relief—or cholecystectomy. Surgery should be offered to any individual who, like Ms. J, meets the Rome III diagnostic criteria and has an abnormal HIDA scan. Recent studies have raised questions about the correlation between HIDA results and postoperative relief,11,12 however, and indicate that patients who have classic biliary symptoms and a normal HIDA scan often have good postoperative outcomes, as well.11,15

A careful workup is key to ensuring maximal benefit from surgery. The resolution of symptoms with a cholecystectomy when the Rome III criteria are followed for patient selection has been found to be close to 90%.11,15-20 Two recent studies have examined the resolution rate for FGBD, with conflicting results.11,12 Both studies were based on long-term postoperative follow-up, ranging from 6 to 24 months. The main difference was the selection bias used in determining eligibility for the study.

The initial selection criteria for the study by Carr et al (N=93) were presenting symptoms (either classic or atypical), followed by a typical workup. The long-term resolution rate for those with classic gallbladder symptoms was 88%11—close to the 90% associated with the Rome III guidelines. The study by Singhal et al (N=141)12 was done retrospectively, using objective data from tests (ie, normal ultrasound and liver biochemistries and abnormal HIDA) rather than patient history as the criteria for inclusion. Among participants in the Singhal study, the long-term resolution rate was just 57%.

Ironically, the patients in the Carr study who had atypical symptoms had mixed postoperative results. The rate of long-term resolution for this cohort was 57%—the same as the overall resolution rate found by Singhal et al.11,12 The fact that a group of patients who presented atypically had the same postoperative resolution rate as those for whom tests (rather than symptoms) were used as the selection criteria illustrates the importance of presenting symptoms as a prognostic indicator.

CASE Ms. J opts for a cholecystectomy and you refer her to a general surgeon. At her annual exam the following year, she reports that she has been symptom free since the surgery.