Data analysis

Kaplan-Meier estimates describe the distribution of weaning times for the 2 sites. A log-rank test was used to assess group differences. Relationships between demographic factors and time of weaning were assessed by Cox regression analysis. Discrete survival analysis was used to determine whether variables measured on a weekly basis were related to breastfeeding cessation. Hazard ratios describe the association of the exposures between women who stopped breastfeeding at a given time and those who continued. Because breastfeeding cessation was a rare event in later weeks of the study, as were certain clinical or behavioral breastfeeding factors, weeks 4-12 were collapsed into a single interval. Two variables, number of daily feedings and duration of each feeding, were examined only in the first 3 weeks because the information was often missing beyond 3 weeks. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.25

Results

Description of subjects

A total of 1057 women agreed to be contacted. Of those, 946 (89.5%) participated in at least 1 interview. Of the 111 women who did not participate, 11 refused and 100 could not be located. Six hundred fifty-eight (69.6%) women completed all 4 interviews. The 56 women who entered the study at week 6 because they could not be reached for the first interview were similar in all factors to women who entered earlier. Of the 946, 711 (75.2%) were from Michigan and 235 (24.8%) were from Nebraska.

Subjects from Michigan were significantly more likely than those from Nebraska to be older than 30 years (52.0% vs 38.3%), have at least a bachelor’s degree (62.9% vs 48.5%), have 3 or more children (38.5% vs 19.6%), and have had a vaginal delivery (99.6% vs 77.0%) (Table W1).* The groups were similar in race, household income, and marital status.

Demographic factors

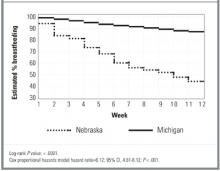

A total of 673 women (71.1%) continued breastfeeding until 12 weeks; 28% were exclusive breastfeeders. Michigan women were more likely to breastfeed at weeks 2 through 12 than their Nebraskan counterparts (P < .0001, Figure). A college degree was associated with 40% less weaning (Table 1). Age and annual household income were directly related to continued breastfeeding at both sites. Number of children in the household was not associated with termination. Previous breastfeeding experience showed a nonsignificant but consistent trend toward lower weaning risk.

TABLE 1

Relationships of demographics and other characteristics with time to weaning, by site

| Characteristic | Michigan women HR* (95% CI) | Nebraska women HR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Older than 30 years | 0.5 (0.3,0.8) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) |

| BA/BS or higher | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

| Number of children in household | ||

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) |

| 3 or more | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) |

| Household income ≥ $50,000 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) |

| Breastfed previously | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) |

| Nonvaginal birth | † | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

| NOTE: Bold numbers are significant at P < .05. | ||

| HR denotes hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BA, bachelor of arts degree; BS, bachelor of science degree. | ||

| *A hazard ratio of <1 indicates that subjects with this characteristic were less likely to wean during the 12 weeks. Unless otherwise noted, the referent group is the converse (eg, age < 30 years is the referent group for those older than 30 years). | ||

| †Too few observations to provide meaningful results. | ||

FIGURE

Probability of breastfeeding, by site, by postpartum week

Clinical and behavioral factors

Because time to weaning differed significantly by site, the survival analyses of clinical and behavioral factors were performed separately for Michigan and Nebraska and controlled for education, age, and previous breastfeeding experience.

During the first 3 weeks, Michigan women with mastitis were nearly 6 times more likely than Michigan women without mastitis to stop breast-feeding in the week of diagnosis (Table 2). Women from Nebraska showed nonsignificant results in the same direction in weeks 4 to 12. (No women from Nebraska with mastitis terminated during weeks 1 through 3.) Although nipple sores and cracks were not associated with weaning, breast pain was associated with weaning. For each day of pain in the first 3 weeks, there was a 10% increase in risk of cessation among Michigan women and a 26% increase among Nebraska women. The association between pain and weaning in weeks 4 through 12 is less clear. In these later weeks, women who reported pain were unexpectedly 75% to 80% more likely to continue breastfeeding than women who did not report pain, yet for Nebraska women the number of days with pain remained significantly associated with breastfeeding cessation.

Subjective depression and breastfeeding cessation were not related. The association between daily sleep and weaning varied by site. During weeks 4 through 12, Michigan women with more daily sleep were less likely to terminate. An opposite, but marginally significant trend, was observed for Nebraska women. Weaning was not associated with outside household help. Nonvaginal birth was not associated with weaning for Nebraska women. (There were only 2 cesarean sections in the Michigan group.)