Many public health departments have TB programs wherein patients with active or latent TB can receive free care and medication.

State and local public health departments have the responsibility of monitoring TB care provided by physicians in the community, to insure it is applied according to guidelines and that it is completed. The intrusiveness of this can be minimized with regular communication and appreciation of the roles and responsibilities of each party.

Excellent review of the basics of TB screening, diagnosis, and treatment: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis. 4th ed. Atlanta, Ga: CDC; 2000.

Self-study modules on TB: CDC. National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Divisionof Tuberculosis Elimination. Available at: www.phppo.cdc.gov/PHTN/tbmodules.(Accessed on September 8, 2003.)

Training modules and statistics on TB diagnosis, treatment, and epidemiology, including state-specific analyses: CDC. National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchstp/tb/default.htm. (Accessedon September 8, 2003.)

The most recent, comprehensive description of TB treatment recommendations: Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, et al. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:603–662.

Prospects and trends

More reliable testing. The TB skin test is an imperfect screening tool. The development of a blood test for TB antibodies has progressed and will be evaluated and standardized. It will likely be a useful clinical and epidemiological tool in the near future.

Tuberculosis secondary to HIV. By some indicators, the rate of HIV infections has recently increased. This factor, combined with the increased life span of those with HIV, has the potential for reversing some of the recent progress in slowing TB rates. The continued development of anti-HIV medications and availability of the medications through AIDS/HIV treatment programs could help make those who are HIV infected less susceptible to TB infection and disease activation.

Tuberculosis and immigration. It is likely that as endemic TB declines in the US, a higher proportion of TB infections will occur in those who are foreign born and move to this country (see “Trends reversing in tuberculosis”). This underscores the global nature of public health and the importance of international collaboration in the control of contagious diseases and other public health threats.

At the turn of the 20th century, TB was the leading cause of death in the US and much of the world. Public health efforts and improved living conditions resulted in a steady decline in TB morbidity and mortality until the mid-1980s.

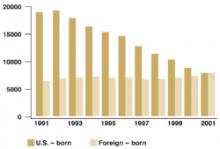

At that time a combination of events—the HIV epidemic, increased immigration from countries with high TB rates, and a decline in funding for TB control programs—resulted in a reversal of this downward trend and for several years there were increases in US TB rates. Of equal concern was an increase in multidrug resistance. These worrisome trends were reversed in the early 1990s and since that time TB rates have again been declining. In 2001 there were 15,989 new cases of TB in the US for a rate of 5.6/100,000. An increasing proportion of cases have been occurring among those born in countries with high TB rates; in 2001 49% of all those with TB in the US were foreign-born.

Increasing proportion of foreign-born TB cases

Number of tuberculosis cases in US-born vs foreign-born persons, United States, 1991–2001. Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

Correspondence

1825 E. Roosevelt, Phoenix, AZ 85006. E-mail: dougcampos@mail.maricopa.gov.