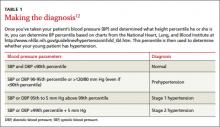

The diagnostic parameters for pediatric hypertension are listed in TABLE 1.12 The higher systolic or diastolic BP percentile value is used to determine a child’s overall BP category. A child is considered normotensive if the BP is <90th percentile. Hypertension is an average systolic or diastolic BP that is ≥95th percentile on at least 3 separate occasions. Stage 1 hypertension is BP levels ranging from the 95th percentile to 5 mm Hg above the 99th percentile, and stage 2 hypertension is BP levels greater than 5 mm Hg above the 99th percentile.

For example, assume you are evaluating a 12-year-old boy who is 61 inches tall and has a BP of 129/87 mm Hg. According to the CDC growth charts, his height puts him in the 75th percentile for his age. Using the NHLBI chart, you determine that he falls in the 95th-99th percentile for BP, and thus, using the categories in TABLE 1, is given a diagnosis of Stage 1 hypertension.

Accurate BP measurement requires using an appropriate cuff size that covers 80% of the child’s upper arm. When the child is between cuff sizes, use the larger cuff because small cuffs overestimate BP readings. BP readings should be taken on the right arm with the arm supported at heart level after the child has been sitting quietly for at least 5 minutes.12 One study showed that the initial BP readings taken in the triage area were significantly higher—often by >10 mm Hg—compared with follow-up measurements in the examination room.22

The preferred method of BP measurement is auscultation; however, oscillometric devices also are acceptable. These devices are easier to use, help eliminate digit bias, and minimize observer variation, but they typically read approximately 6 to 9 mm Hg higher than auscultation.23 For any BP measurement obtained by oscillometry that is >90th percentile, repeat the measurement by auscultation at least twice during the same office visit, and use an average of the repeated measurements.12 Obtain measurements of a lower extremity when you suspect congenital heart disease (eg, aortic coarctation). For any patient in whom you confirm a BP measurement >95th percentile, repeat the measurement within 2 weeks; for BPs >99th percentile, reevaluation should occur within one week.

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM). Because BP measurements have a circadian pattern (higher during the day and reduced by 10% during sleep24) an ABPM device that provides 50 to 60 readings over 24 hours can be useful when evaluating children and adolescents for white-coat hypertension (elevated clinic BP with normal ambulatory BP), masked hypertension (normal clinic BP with elevated ambulatory BP), prehypertension and secondary hypertension (BP generally does not follow circadian patterns).25 ABPM is more accurate than BP self-measurement, but usually is limited to children older than age 5

Steps to take for clinical evaluation

Start by conducting a thorough history and physical examination, looking for information that can help you select the most appropriate tests for the next phase of evaluation.8,12 Calculate the patient’s BMI to screen for obesity, ask about a family history of hypertension or CVD, and determine if the patient is taking any medications that might cause hypertension, such as amphetamines, corticosteroids, or cyclosporine.8 Assess for signs and symptoms that suggest an underlying disease, such as renal disease (hematuria, edema, fatigue) or heart disease (chest pain, exertional dyspnea, palpitations).12

All children diagnosed with hypertension should be screened for secondary causes (TABLE 2). The recommended evaluation is to obtain a renal function panel, electrolytes, urinalysis, urine culture, complete blood count, renovascular imaging, and echocardiogram.12 The most common etiologies for secondary hypertension are renal parenchymal disease (68%), renovascular abnormalities (10%), and endocrinopathies (10%).26 Other causes, such as aortic coarctation, obstructive sleep apnea, iatrogenic factors (eg, toxins, medications, drugs of abuse), and genitourinary abnormalities, account for only a small percentage of cases and should be investigated as clinically indicated.26

Renovascular assessment depends on facility expertise. Imaging options include renal ultrasound (with or without Doppler), computed tomography angiography, renal flow scan, and magnetic resonance angiography. These studies have similar sensitivities and specificities.27 For patients in whom you strongly suspect renovascular disease, renal arteriography (digital subtraction angiography) provides the best images, although it is the most invasive study.27

Refer children and adolescents who are found to have significant abnormalities during the initial evaluation to the appropriate specialist. BP measurements often improve when secondary causes are treated.