Antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections among U.S. children more than doubled from nearly 1.5% to 3% over a 12-year period.

While such infections remain uncommon in the pediatric population, the trend, as in adults, is a rising one, based on research published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu010]). The findings also indicate that third-generation cephalosporin–resistant (G3CR) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing infections have increased across pediatric patient settings, geographical regions, and age groups.

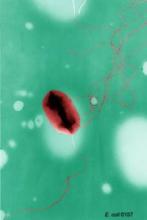

Looking at 368,398 pediatric isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis collected from about 300 clinics nationwide between 1999 and 2011, researchers led by Dr. Latania K. Logan of Rush University in Chicago found that the prevalence of G3CR infections had increased from 1.39% in the 1999-2001 period to 3% in 2010-2011. The prevalence of ESBL infections rose from 0.28% to 0.92% across the same study periods.

The children ranged from 1 to 17 years old, with about 38% of isolates taken from 1-5 year olds. These younger subjects represented 47.1% of G3CR and 50.5% of ESBL-producing isolates.

The vast majority of isolates were E. coli; most were taken from urine, most were taken in outpatient settings, and most were from girls – about 15% of the isolates examined in the study came from boys. However, among those positive for G3CR and ESBL types, the proportion that affected boys was 32.4% and 39.2%, respectively.

More than half of all ESBL isolates came from outpatient settings. The high prevalence outside hospital settings, Dr. Logan and her colleagues wrote, suggested that these could be CTX-M-type ESBL, a community-acquired type that "results in multidrug-resistant infections in people with no significant history of health care exposure."

"Additional studies in children to assess risk factors for acquisition, prevalence in ambulatory and long-term health care facilities, and the molecular epidemiology of ESBL-producing bacteria are warranted," the researchers wrote.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations to their study, including its limited data on patient characteristics and prior medical histories, and its inability to capture isolates from infants younger than 1 year. And only a small proportion – 0.22% – of isolates in the study came from children in long-term care facilities, which are known reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for adults.

However, a linked case-control study also led by Dr. Logan and published concurrently with the larger study (J. Ped. Infect. Dis. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu011]) did uncover several relevant risk factors related to ESBL infections in children, including in children younger than 1 year.

For that study, Dr. Logan and her colleagues examined 30 subjects aged 0-17 years with ESBL–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections recruited at two Chicago hospitals over a 4-year period, comparing these to uninfected controls. The researchers also recruited 30 children with non-ESBL–producing bacterial infections and compared those to uninfected controls.

The median age of ESBL cases in the study was 1.06 years. Prevalence of ESBL infection was 1.7% during the study period and was not seen as changing significantly over time. Of the ESBL infections, 30% occurred in outpatient settings, 63% were isolated from urine, and 60% were E. coli. The majority of ESBL infections (77%) were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics.

ESBL cases were more likely to have gastrointestinal (P = .001; odds ratio, 5.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-17.0) or neurological (P = .001; OR, 3.3; CI, 1.1-3.7) comorbidities compared with controls, and non-ESBL cases were also more likely to have gastrointestinal comorbidities compared with controls (P = .014; OR, 3.6; CI, 1.2-10.1). Of the 16 children with neurological comorbidities and EBSL infection, half had a history of cerebrovascular disease or diffuse encephalopathy, and 75% of infections were associated with a foreign body such as a catheter or ventilatory device.

Dr. Logan and her colleagues did not see worse outcomes in children with ESBL infections, as mortality and length of hospital stay after infection did not differ significantly between cases and controls. Nor was ESBL infection found to be significantly associated with recent antibiotic exposure. However, the authors acknowledged that this could have been due to the study’s small sample size.

Dr. Logan and her coauthors received funding for their research from Rush University, the Children’s Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Princeton University. None of the authors declared conflicts of interest.