First, through interview or questionnaire, we gathered standard sociodemographic data. Second, we focused on general health issues, chronic medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, chronic medication consumption, and number of visits. We derived this information from computerized medical records. Third, through the questionnaire, we inquired about the reason patients used a list, and asked patients to subjectively rate their memory and give the general reasons for their visit.

The control group consisted of patients recruited consecutively at arbitrary points in time until its size matched that of the study group. These patients volunteered information to the same line of inquiry. Some members of the groups chose to complete the questionnaires in writing without the physician’s assistance.

Statistical analysis

We processed results using SPSS software. We applied the x2 test for statistical interpretation and set statistical significance at P<.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five men and twenty-nine women ages 21 to 82 years of age comprised the group of patients presenting with a list. All patients who met inclusion criteria agreed to cooperate. TABLE 1 summarizes the sociodemographic data. The control group consisted of 30 men and 22 women ages 20 to 86 years of age.

There was no statistically meaningful difference in gender ratio between the groups. In the study and control groups, respectively, the average number of children of each subject was 4.1 and 3.5, years of formal education were 10.8 and 10.6, and years since immigration were 40.5 and 37.8 (P=.42). Marital status and average household income were also similar in both groups.

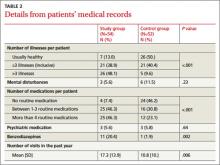

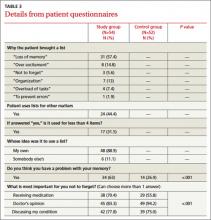

Statistically significant findings with the study group were relatively older ages and likelihood to be pensioners. The study group included fewer employed individuals and fewer housewives (P<.001). They also were more likely to have more than 3 chronic diseases (48.1% vs. 9.6%; P<.001) and took more long-term medications, including benzodiazepines (TABLE 2). They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls and reported a perceived increase in memory loss (TABLE 3). There were no significant differences between the groups in psychiatric or personality disorders, as determined by surveying patients’ electronic records.

The reasons most commonly given for using a list indicated a desire to completely satisfy the objectives of the visit. Most of the individuals decided to prepare a list on their own initiative without persuasion from any external source.

DISCUSSION

In an survey of 216 family physicians and internists at the University of Wisconsin, >60% of respondents said their patients bring in lists very often or sometimes.11 This figure seems much higher than would be found in our country (Israel). However, the practice is certainly common; although the actual frequency is unknown.

Other published observations about list use. Middleton et al12 studied the effects of planned use of agenda forms, completed by patients and handed to physicians at the outset of a primary care visit. The written agenda significantly increased the number of problems identified in each consultation. Patient satisfaction increased and deepened the doctor-patient relationship. However, the duration of consultations also increased.

A commentary by Schrager et al11 acknowledges that lists are dreaded by some physicians. Particularly if the expectation is for a patient to present with a single complaint, the appearance of a list may be an unwelcome surprise, suggesting a collection of separate complaints. And compulsive and somatizing patients can raise a series of overwhelming issues that encumber a short visit. But the commentary points out that, in general, fear of a list is unfounded, and that acceptance without prejudging can lead to a constructive outcome.

A number of researchers have examined the relationship between negative physician attitudes and certain patient attributes such as sociodemographic characteristics or a persistent emotional component to their ailments.13 Katz14 reported that patients who generated the most frustration were those who demanded a cure, those who added unrelated complaints at the end of the visit, malingerers, and those who refused to accept responsibility for their own maladies. List users, we believe, should not be lumped in with this group automatically.

In our study, patients with lists did request more frequent consultations. However, this correlated closely with a heavier burden of disease. Using patient-centered communication to set the agenda for the visit and address the entirety of patients’ concerns has been shown to improve not only patient satisfaction but also adherence to treatment recommendations.15,16 One way for patients to become more involved in their care is to bring a list of questions to each visit, as advised by AHRQ.