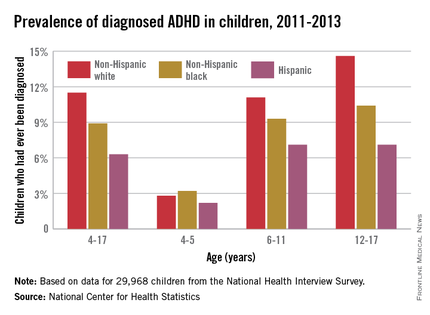

Hispanic children aged 6-17 years were significantly less likely to have ever been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder than were non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black children in 2011-2013, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In children aged 6-11 years, the prevalence of a lifetime ADHD diagnosis was 11.1% for non-Hispanic whites, 9.3% for non-Hispanic blacks, and 7.1% for Hispanic children in 2011-2013. For children aged 12-17 years, Hispanic diagnosis remained at 7.1%, while the rate increased to 14.6% for whites and 10.4% for blacks.

There were no significant differences in diagnosis between ethnicities for children aged 4-5, with ADHD rates ranging from 2.2% to 3.2%. Overall, 11.5% of white children aged 4-17 had ever been diagnosed with ADHD, compared with 8.9% of black children and 6.3% of Hispanic children, the NCHS reported.

Boys of all ages were much more likely to have a diagnosis of ADHD than were girls in 2011-2013, with 4.3% of boys aged 4-5 years receiving a diagnosis, compared with 1.2% of girls. This gap widened to 13.2% and 5.6% for those aged 6-11 years and to 16.3% and 7.1% for those aged 12-17 years.

Children with public insurance were more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD compared with those who had private insurance and those who were uninsured, with an overall rate of 11.7% for publicly insured children, 8.6% for the privately insured, and 5.7% for the uninsured. Living in a household making less than 200% of the federal poverty threshold increased ADHD diagnosis in children aged 4-11 years, but this effect disappeared in children aged 12-17 years, according to the NCHS report.

“In view of the economic and social costs associated with ADHD and the potential benefits of treatment, the continued surveillance of diagnosed ADHD is warranted,” said Patricia N. Pastor, Ph.D., and her associates at the NCHS, Hyattsville, Md.

The NCHS report used data for 29,968 children from the National Health Interview Survey.