Not too long ago at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston, a woman with widely metastatic melanoma, who had been planning her own funeral, was surprised when she had a phenomenal response to immunotherapy.

She was shocked to learn that her cancer was almost completely gone after 12 weeks, but she was stunned when she developed a rash that made her oncologist think she needed to stop treatment.

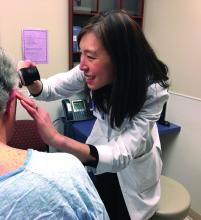

To be certain, though, he paged a dermatologist working in the cancer center who quickly determined that the rash was treatment-related psoriasis and not life threatening. Phototherapy, topical steroids, and apremilast (Otezla) did the trick. “We got her psoriasis under control so that she was able to stay on her immunotherapy, which had saved her life,” said dermatologist Nicole LeBoeuf, MD, who is the director the Skin Toxicities from Anticancer Therapies Clinic at the cancer center and was involved with the case. Stories like that are why and why oncodermatologists are likely to become more common in cancer centers nationwide in the not-too-distant future.With traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, there were a few well-defined skin side effects that oncologists were comfortable managing on their own with steroids or by reducing or stopping treatment for a bit.

But over the last decade, new cancer options have become available, most notably immunotherapies and targeted biologics, which are keeping some people alive longer but also causing cutaneous side effects that have never been seen before in oncology and are being reported frequently.

An urgent need

As cancer treatment becomes more complex, oncologists are discovering that it helps to have a dermatologist on hand who can recognize and manage these problems and decide whether treatment needs to be stopped.Currently in the United States, there’s only a handful of dedicated supportive oncodermatology services, which can be found at major academic cancer centers such as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s, but the residents and fellows being trained at these centers are starting to fan out across the country and set up new services.

One day, it’s likely that every major cancer institution will have “a toxicities team with expert dermatologists,” said Dr. LeBoeuf, who launched the supportive oncodermatology program at Dana-Farber in 2014 and who now runs it with a team of dermatologists and clinics every week. Dr. LeBoeuf is a leader in the field, like the other dermatologists interviewed for this story.

With all the new treatments and with even more on the way, “there’s an urgent need for dermatologists to be involved in care of cancer patients,” Dr. LeBoeuf said.

The problem

Newer treatments have made cancer less lethal in some cases, but almost all of their targets also play a role in the skin, and that causes problems.Immunotherapies like the PD-1 blocking agents pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) – both used for an ever-expanding list of tumors – amp up the immune system to fight cancer, but they also tend to cause adverse events that mimic autoimmune diseases such as lupus, psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. Dermatologists are familiar with those problems and how to manage them, but oncologists generally are not.

Meanwhile, the many targeted therapies approved over the past decade interfere with specific molecules needed for tumor growth, but they also are associated with a wide range of skin, hair, and nail side effects that include skin growths, itching, paronychia, and more.

Agents that target vascular endothelial growth factors, such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and bevacizumab (Avastin), can trigger a painful hand-foot skin reaction that’s different from the hand-foot syndrome reported with older cytotoxic agents.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, such as erlotinib (Tarceva) or gefitinib (Iressa), often cause miserable acne-like eruptions, but that can mean the drug is working.

It’s hard for oncologists to know what’s life-threatening and what isn’t; that’s where dermatologists come in.

A solution

“There needs to be specialists who recognize what is happening. It’s not just about helping patients feel better, although that’s a huge component; it’s also about helping decide what their future care will be. Unless you see these reactions a lot, you will not have any idea what you are looking at,” said Jennifer Choi, MD chief of the division of oncodermatology at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago.When problems come up, oncologists and patients need answers right away, she said. There’s no time to wait a month or two for a dermatology appointment to find out whether, for instance, a new mouth ulcer is a minor inconvenience or the first sign of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and the last thing an exhausted cancer patient needs is to be told to go to yet another clinic for a dermatology consult.

For supportive oncodermatology, that means being where the patients are: in the cancer centers. “Our clinic is situated on the same cancer floor as all the other oncology clinics,” which means easy access for both patients and oncologists, Dr. Choi said. “They just come down the hall.”